By CYNTHIA HENDERSON

Raymond Graham’s history in shellfishing runs as deep as the currents of the Newport River that flows past his home in Mill Creek. As a shellfish dealer, Graham carries on a family tradition that goes back at least to his grandfather. But in his lifetime, much has changed.

At water’s edge stands the oyster-shucking house his family operated for 50 years. It is silent now — filled with dusty artifacts of a once-thriving independent shellfishing trade.

Each Friday, Graham roasts chickens on a hand-made covered grill. The cookout is a weekly ritual for shellfishers who sell him oysters and clams.

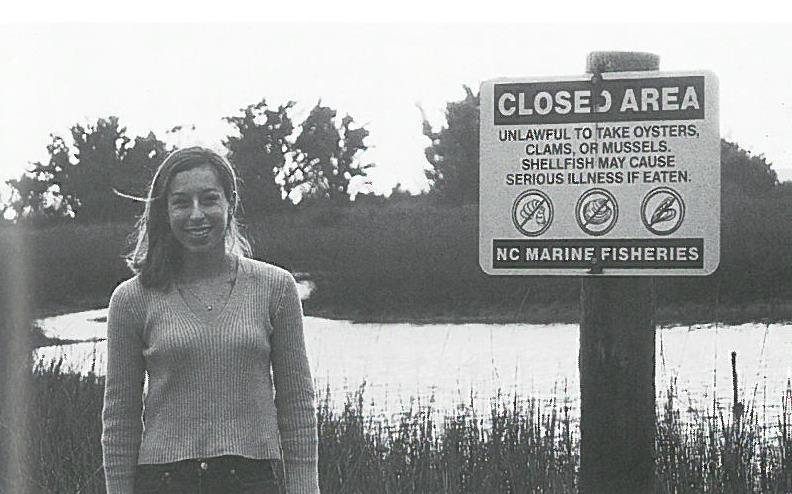

Angela Corridore at a shellfish closure near the Duke Marine Lab in Beaufort. Her master’s study brought attention to the impacts of such closures on those who make an income fishing for oysters and clams. Photo by Cynthia Henderson.

A while back, a graduate student joined the men at Graham’s picnic table to share lunch and ideas about the state of shellfishing. Angela Corridore, then studying coastal management at the Duke University Marine Lab in Beaufort, was focusing her master’s project on the impacts of pollution-related shellfish closures on the people who shellfish for a living.

Her study, funded by the N.C. Fishery Resource Grant Program (FRG), reveals a culture and heritage little known or understood in higher, drier regions of the state.

Certain areas of water are closed to shellfishing temporarily when the potential for pollution is great, as when a certain amount of rain falls within 24 hours.

“If water doesn’t meet the standards for its intended use,” Corridore says, “it violates the Clean Water Act,” a 1977 amendment to the Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1972. Because the Newport River was once a productive shellfishing area, being closed to shellfishing means it is not meeting clean water standards.

Mike Marshall, central district manager of the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries (DMF), says that closures generally have followed coastal development.

“The most recent fairly large-scale closures have been around the Pamlico Sound. More closures have been in the southern areas in the past,” he says.

Development decreases the permeable land surfaces that absorb and filter rainwater. Without such filtering, runoff from storms carries microorganisms from human and animal waste — collectively known as fecal coliform bacteria — into waterways. These bacteria and certain viruses are associated with illnesses like typhoid, cholera, gastroenteritis, salmonella and hepatitis A, according to Corridore.

Shellfish closures, therefore, are environmental actions intended to protect public health. But Corridore sees social implications as well.

“Environmental issues aren’t affecting just the environment itself, but people,” she says. “The human component gets ignored.”

As part of her FRG project, Corridore used a survey and personal interviews to discover how shellfish closures affect people who work on the water. FRG, which provides funding for research carried out by those involved in coastal or seafood-related industries, also funds projects such as Corridore’s that include significant participation from the fishing community.

For Corridore, the project was more than an academic exercise. Unsatisfied with a superficial understanding, she went out with shellfisher Charlie Antwine to experience tonging for oysters herself. “It was hard work,” she says emphatically.

The Issues

The men around Raymond Graham’s picnic table are as likely to talk about temporary shellfish openings as closures. So common are closures, Graham says, that shellfishing is no longer a dependable way to make a living.

“Most people working here now are retired,” he says. “Anybody with a family can’t make a living out there. They have to do something besides shellfishing.”

In addition to limited accessibility to shellfish waters, shellfishers have seen a dramatic decline in oyster populations. Parasitic diseases like Dermo, which became a problem in the late 1980s, and MSX have contributed to this decline. And then there were detrimental effects from hurricanes in recent years.

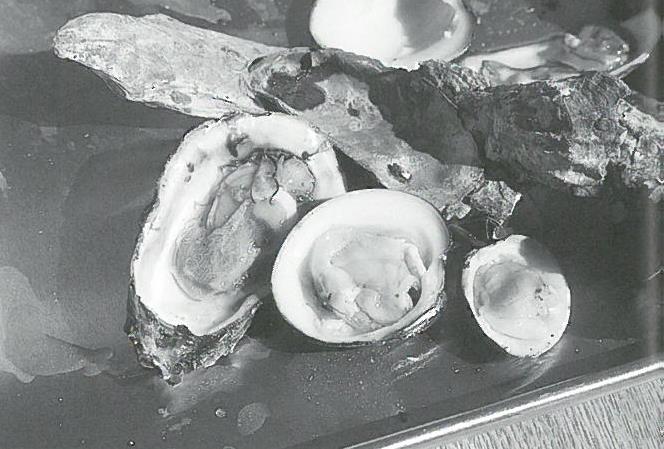

Many oysters served in restaurants and at seafood festivals in North Carolina are now from out-of-state. Photo by Scott D. Taylor.

As Graham puts it, “Hell, we’ve been hit by everything but leprosy.”

Antwine, who shellfishes part time, is retired from the N.C. Department of Transportation. He sees pollution as a major problem but questions the standards used to determine closures. “We can sell oysters from Mississippi, but ours can’t be bought. We don’t want to make people sick. We want to provide a product people will eat,” he says.

Graham’s son, Raymond Jr., agrees. He also shellfishes only part time. In addition to bacterial pollution, he blames household chemicals like chlorine and discharges from nearby municipalities for problems with shellfishing. “Twenty-five years ago, we didn’t have the chemicals like we do today,” he says.

Cam McNutt of the N.C. Division of Water Quality in Raleigh says that point sources such as municipal discharges are actually becoming “less and less of a problem.”

“We removed a discharge source out of the New River from Jacksonville and Camp LeJeune in 1998, consolidating its discharges into one high-quality treatment facility,” he says. “The water quality there has recovered substantially since then.”

However, he says, “Stormwater runoff is becoming more and more of a problem. It’s not one thing that causes water quality problems. It’s usually multiple things.”

“Standards for SA (shellfishing) waters are some of the most stringent of all classifications,” says McNutt. Water for swimming, for example, can have bacterial counts of 200 colonies per 100 ml of water. For shellfishing, the limit is 14 colonies. The reason for the higher standards, he explains, is that shellfish concentrate the bacteria.

The Way it Was And Is

Raymond Graham, a former member of an advisory committee for the N.C. Marine Fisheries Commission, focuses on the present but doesn’t forget the past. It’s a trait that is evident in his speech. “And that’s the way it is,” is his frequent summation of things.

And “the way it is” is very much a product of how it was.

The first dollar Graham ever made, he says, was culling 20 bushels of oysters one Saturday when he was around nine. Before that, the most he had earned was 75 cents for a whole week “working in beans,” so the dollar earned in a single day made an impression. He may not remember what he did with the money, but Graham does recall, “I looked at it a long time.”

Graham also shoveled oysters for his father, he says. On Saturdays he would get 25 cents for movies and popcorn. John Wayne was a favorite.

“Everybody went to Beaufort by boat, and tied up at the hardware store,” he says, recalling Beaufort as a working fishing village. “Fruits and vegetables were left out all night (by merchants), and the town smelled like a fish. All of Front Street is now a tourist attraction.”

These days, when waters are closed to shellfishing, Graham’s love of movies serves him well. “Shutdowns are just another Sunday,” he says with irony. “You sit down, eat and watch some movies.”

“Where closures hurt us,” he explains, “is not being able to consistently fill orders. We used to handle eight or nine hundred bushels a week. Now if a man wants 10 bushels of oysters, we can’t promise we can get 10 bushels, because we can’t be sure we’ll be open. We lost our credibility.”

In its heyday, Graham’s business included Campbell’s Soup in Maryland. Back then, he could handle more clams in a week than he does now in a month.

The business was a family legacy. “When Granddaddy got old, he worked for Daddy. And when Daddy got old, he worked for me,” Graham says.

“Mother opened oysters and took care of the oyster house. Mom was in her 70s before she quit.”

Now, with the oyster house closed and shellfishing providing only part of his son’s income, the generational link to shellfishing is wearing thin. “A young fellow would have to be out of his mind to want to get into this business,” Graham says.

Because few depend solely on shellfishing for a living, the economic impact of closures could be considered small, Corridore says. “The social impact, however, may be quite large because, as fewer people are able to rely on shellfishing for a living, there may be a gradual loss of a local cultural heritage,” she concludes.

And the culture of shellfishing is doubtless a part of the melange that is the state’s collective identity.

DMF’s Marshall recalls his father bringing oysters from the coast home to Rocky Mount for oyster roasts each fall. “It was comparable to a pig picking,” he says. “It used to be a big social event. It’s sad that we’re losing that as a social activity here on the coast.”

Now, at Mill Creek’s annual oyster festival, the oysters come from Louisiana.

“I’m not doing 25 percent of the business I did 10 years ago. When I do, have to compete with oysters from Louisiana,” Graham says.

Skip Kemp, North Carolina Sea Grant mariculture specialist, says, “Shellfish closures also affect shellfish farms, especially if a closure is immediately before a holiday when the market is strong.”

Mariculturists who lease beds may hold onto shellfish until demand is strong and prices are higher, Kemp adds. Thus they miss out on potential profits when closures occur during peak demand.

Regulating Shellfish Waters

Corridore’s analysis examines the roles of various agencies. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency administers the Clean Water Act and requires states to develop a Nonpoint Source Management Program (NPSMP). Shellfish management then becomes an alphabet soup of agencies.

To simplify, managing shellfishing waters involves three arenas — public health, the environment and coastal development. To ensure public health, the Shellfish Sanitation Section of the N.C. Division of Environmental Health (DEH) classifies and tests shellfishing waters. It makes recommendations to the DMF, which issues proclamations and enforces closures.

The N.C. Coastal Resources Commission (CRC) designates Areas of Environmental Concern and establishes regulations to control development. The state’s Division of Coastal Management (DCM) implements the regulations and issues permits for development within the sensitive areas.

One way the CRC protects shellfishing waters is by requiring a 30-foot buffer zone for building along estuarine shorelines.

Dave Beresoff, a commercial fishing representative on the commission, cites a move last fall to protect shellfishing waters even while compromising with builders to allow isolated exceptions to the buffer rule.

“We initiated an exception to the exception. If the commission makes exceptions to the rules, they should never apply to shellfishing waters,” he says.

The N.C. Division of Water Quality (DWQ) coordinates the NPSMP and water quality regulations of the Clean Water Act. Corridore points to a lack of coordination between agencies in the past.

Fortunately, McNutt says, a project is underway to help interagency communication through a shared database. “It’s a multi-user approach,” he says. “It will include information from DEH and will be used heavily by DWQ and Marine Fisheries.”

Gloria Putnam, the state’s coastal nonpoint source program coordinator, says the program is providing funds for high-tech equipment to allow state agencies to map the closure lines. “That information will be entered into the database, along with DEH water quality monitoring data,” she says.

The data will allow the tracking of trends along the coast — and will provide local government and state agencies with information needed to target water quality restoration and protection efforts. “It’s a way to bring us together with information in a more usable format,” Putnam adds. “This will help us. It’s not a panacea, but we’re moving in the right direction.”

“One of the things that may eventually be a useful outcome,” she says, “is having information available online so anyone can see what areas are open or closed.”

And, of course, there is the goal of improving shellfish habitats and increasing harvests. As Putnam says, “I love oysters. And when I get them, I want N.C. oysters. They’re just better oysters because they’re not so big — they’re fresh and they’re salty.”

Tonging for oysters

At daybreak on the Newport River, within sight of Graham’s vacant oyster-shucking house, Charlie Antwine sets out by boat to tong for oysters.

As he motors toward Core Creek, the purple sky goes white with mist, creating a dreamscape in which sky and water are nearly indistinguishable. The motor drowns all other sounds, and cold numbs the face. Ahead of the boat, a dolphin materializes, arches upward in a slow turn, then disappears.

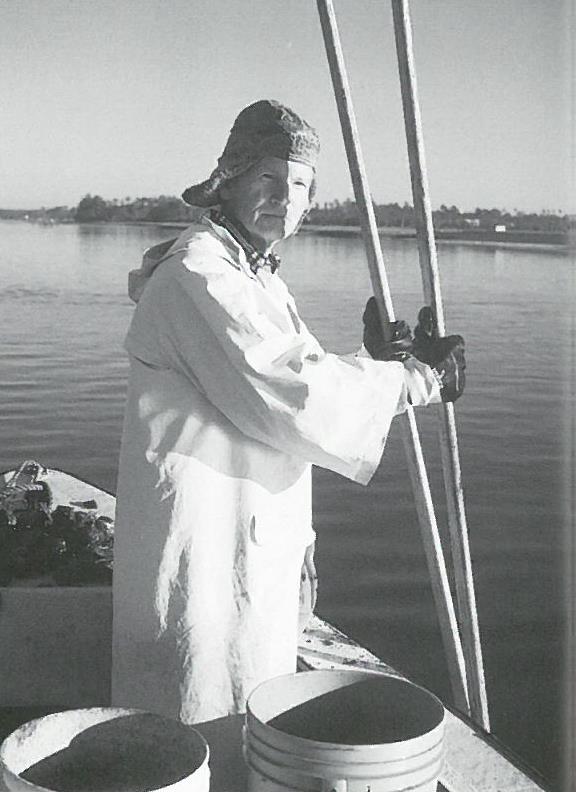

Charlie Antwine tongs for oysters in Core Creek. Photo by Cynthia Henderson.

When Antwine cuts the motor, he says it is rare to see dolphins in the cooler months.

He demonstrates using oyster tongs, which are two long poles joined scissors-fashion with opposing, elongated rakes at the end. He thrusts the tongs down to the hard shell substrate, then brings the wide-apart handles together, which closes the rakes under the water. Hoisting the closed tongs up, he examines the caged contents.

Sometimes the catch is empty shells — sometimes, a single oyster or small cluster of them, or a clam or two. Antwine gauges the size of the shellfish, throwing back those under the size limit. If Nautilus of Greek mythology had been a shellfisher, it would be clear how the exercise equipment got its name. It is, as Corridore says, hard work.

Soon, the sun blazes to orange and work continues as outer layers of clothing are shed. Other shellfishers arrive nearby. Some also are tonging from boats. Others are in wet suits — waist deep in water harvesting oysters by hand.

For the most part, the work is solitary, though some pleasantries are exchanged about what kind of luck each is having or where a closed area was recently opened.

When the catch becomes mainly empty shells, Antwine motors to a new spot and begins again.

Before heading back to Graham’s with his harvest, Antwine gives a tour of other shellfishing areas. Out toward the bridge that connects Morehead City to Beaufort, he goes into a creek. The water appears pristine, but the area is closed temporarily.

Unlike permanent closures, where signs warn that shellfishing is prohibited, temporary closures have no signs. Thus, should a shellfisher not know an area is closed, an entire day’s work might have to be discarded, according to Corridore. All shellfish catches have to be tagged to verify origin.

Continuing the tour, Antwine points to Cross Rock. “You used to get good oysters there, but now it’s dead,” he says. Oyster rocks can die at a certain age, he explains, or they can die from disease.

“Oysters don’t have the resistance they used to, because of pollution,” Antwine says.

Corridore’s final report, according to Trish Murphy of the DMF, may be considered in the development of the next fishery management plan for hard clams and oysters.

For Beresoff, future management has a singular importance. “We’ve done too much too quickly and not seen the consequences down the road,” he says. “Now we have to protect what’s left.”

Angela Corridore is now a Knauss Fellow with the U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy, in Washington, D.C.

This article was published in the Spring 2002 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.