River of Time

The Stunning Old-Growth Forest in the Three Sisters Swamp

North Carolina’s famous Black River holds living bald cypresses that were saplings before Rome was an empire. After finding trees over 2,000 years old, researchers say the river might even nourish bald cypresses that sprouted three millennia ago.

BY JACK HORAN

The rhythm of time stretches back 2,000 years through the ancient bald cypress trees in Three Sisters Swamp along the Black River in southeastern North Carolina.

New research shows the swamp holds some of the oldest trees in the world. Two bald cypress have been documented to be at least 2,624 years old and 2,088 years old, ascertained by counting their annual growth rings and through radiocarbon analysis.

The venerable trees were alive centuries before the advent of Christianity and the English language. David Stahle, a researcher in the department of geosciences at the University of Arkansas, cored the trunks and established the ages of the two trees. He believes even older trees may grow in the swamp and along the river.

“There are surely multiple trees over 2,000 years old at Black River,” Stahle says. “It’s my belief there are some approaching, if not exceeding, 3,000 years old.”

The Black River has been known, for three decades, for the oldest trees on the East Coast. The previous oldest documented tree in the swamp is a bald cypress sampled in 1988 by Stahle and his colleagues. Called “Methuselah,” after the Biblical character who lived for 969 years, the tree was determined to have been growing in 364 A.D., making it about 1,700 years old. But the two 2,000-plus-year-old trees exceed the Methuselah tree in age by nearly 1,000 years.

Julie Moore, formerly of the N.C. Natural Heritage Program, and David Stahle, University of Arkansas, rest their canoe next to the 2,624-year- old tree. Photo by Jack Horan

Stahle’s new findings were published in May in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Research Communications. On the day of publication, he joined staffers from The Nature Conservancy of North Carolina and members of the media in Three Sisters Swamp to view the 2,624-year-old tree by canoe and kayak. In December, The Nature Conservancy bought 319 acres encompassing Three Sisters Swamp and adjoining uplands in Bladen County.

About 25 people paddled a half mile, zig-zagging through the sloughs and channels. At a designated area, Stahle stopped paddling, faced the group and pointed to the surrounding trees with huge buttresses, often gnarled trunks and missing upper limbs shorn off from centuries of storms. The tallest stood 90 feet high.

“You’re in millennium-age trees,” he said. “The entire stream, pretty much, is lined with an ancient forest. This is one of the greatest old-growth forests left in the world.” Stahle and his canoe companion, Julie Moore, former N.C. Natural Heritage Program botanist and an advocate for protecting the trees, then paddled a few more yards. They parked beside the tree that everyone wanted to photograph: the 2,624-year-old bald cypress. Dark green moss covered its lower trunk; alligator weed sprouted in the onyx-colored water around it. Ironically, the tree, with a weathered but straight bole, didn’t look as elderly as some of its knobbly neighbors.

Stahle and a team from Arkansas accidentally discovered the extreme longevity of the Black River trees in the 1980s as part of a study to reconstruct the historical climate of the Southeast. They took corings from trunks and measured the width of individual tree rings. Tree rings are wide in wet years, signifying growth; rings are narrow in dry years with less growth.

The annual ring-growth history taken from the Black River trees and others in Virginia have recorded extended wet and dry years over the centuries. The history includes long-term droughts that likely impacted English settlements on Roanoke Island in 1587 and Jamestown in 1607, according to the study.

In 2018, Stahle said he agreed to core the two 2,000-year-old trees and count their growth rings to raise awareness of the unique stand of ancient trees 45 miles northwest of Wilmington. “If we could really prove there are individual living trees that are 2,000 years old. . . that information could help advance conservation of the trees along the Black River.”

Angie Carl, a Nature Conservancy staffer who oversees Three Sisters Swamp, guided Stahle to the two aged cypresses, which were well into their prime before the Roman Empire was established.

Three Sisters Swamp, about a mile long and a half-mile wide, holds the greatest concentration of ancient trees on the Black River. The Methuselah tree lives here as well. Stahle said bald cypress grow very slowly in the acidic, low-nutrient waters of the Black.

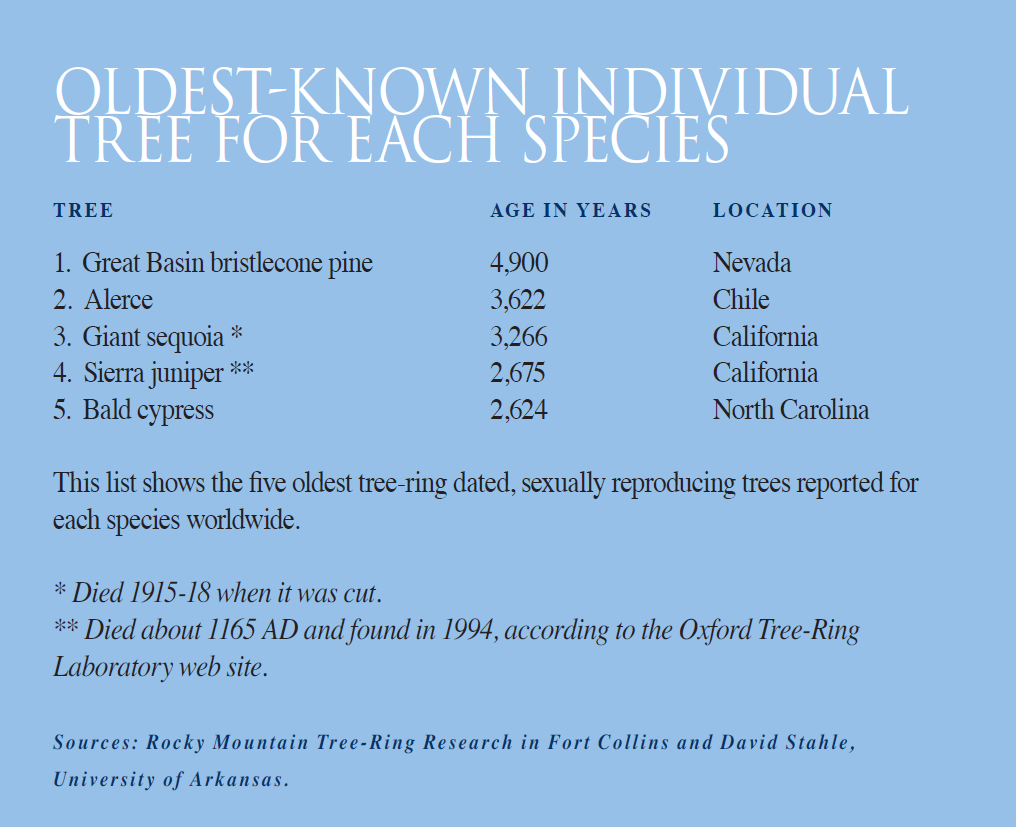

The finding of the 2,624-year-old tree elevated bald cypress into fifth place for longevity among all sexually reproducing tree species on Earth. The oldest species on record is a Great Basin bristlecone pine; one in Nevada has been dated at 4,900 years, according to a list compiled by Rocky Mountain Tree-Ring Research in Fort Collins, Colorado.

The Black River trees have survived deluges and droughts, hail and hurricanes. They also have escaped logging over the years, likely because many are partly hollow and wouldn’t have made good lumber, Stahle said.

The Three Sisters Swamp trees, owned by The Nature Conservancy, aren’t in danger of being logged. The conservation group has protected more than 16,000 acres through ownership and easements along the Black, a tributary of the Cape Fear River, safeguarding other cypress as well.

To preserve and showcase the trees, the N.C. Parks and Recreation Division in 2017 proposed a state park along the Black. Opposition arose from some residents. The proposal was “dropped by the legislature due to lack of community support,” parks spokeswoman Katie Hall said by e-mail. “If the community changes their opinions and comes to be supportive about it, we could revisit the possibility.”

Stahle’s study concluded the Black River potentially holds more 2,000-plus-year-old trees: “Because we have cored and dated only 110 bald cypresses at this site, a small fraction of the tens of thousands of trees still present in these wetlands, there could be several additional individual bald cypress over 2,000 years old along the approximately 66-mile reach of the Black River.”

The future of the ancient trees — particularly those in private ownership — is uncertain. Altogether, the study says, the old-growth cypresses along the Black “remain threatened by logging, water pollution and sea-level rise” and that thousands of acres “with high-quality ancient forests remain to be protected.”

Without permanent protection, Stahle says, the primeval but privately-owned trees “could become garden mulch.”

How to See the Ancient Bald Cypress

A no-fee Wildlife Resources Commission boat ramp is among several points of access to the Three Sisters Swamp on the Black River. Photo from NC Wetlands

Want to see the ancient bald cypress? Three Sisters Swamp lies between the State Road 1550 bridge and the N.C. 53 bridge on the Black River in Bladen County. Only canoes and kayaks can maneuver through the swamp.

For a 9.5-mile float to Three Sisters Swamp, begin at Henry’s Landing, a private landing 1.5 miles downriver from the State Road 1550 bridge. Launch fee is $5 per canoe or kayak.

It’s 5 miles to the upper end of the swamp, 0.5 miles through the swamp, and 4 miles to a private landing at the N.C. 53 bridge. The fee there is $3 per boat. Another 1.7 miles downriver is a no-fee Wildlife Resources Commission boat ramp.

Paddlers unfamiliar with the swamp should go with an experienced group or an outfitter; there are no marked trails. Minimum river flow for paddling through the swamp without having to drag canoes or kayaks over sand bars is 500 cubic feet per second, measured at the upstream U.S. Geological Survey gauge at Tomahawk.

An earlier version of this story appeared in the Charlotte Observer and the Raleigh News and Observer. The National Science Foundation has supported the research of Stahle and his colleagues.