Coastal Connections

Hatteras Island Students Tackle Coastal Change

BY EVAN FERGUSON

Evan Ferguson is a 30-year resident of Cape Hatteras, where she teaches at Cape Hatteras Secondary School. She is a mother of two boys who love to fish, surf, and hunt with their father, a tugboat engineer. She worked with North Carolina Sea Grant on the Cape Shark Project and celebrates the state’s coast, fisheries, and unique culture. Before the COVID-19 outbreak, her students conducted the “Student Perspectives on Coastal Change” study, which she discussed at the North Carolina Coastal Conference and writes about here.

The iconic Cape Hatteras Lighthouse stands formidably after its much-heralded relocation to escape shoreline erosion. Courtesy of Division of Tourism/VisitNC.com.

Hatteras Island’s youth are strong and resilient. “Salty,” some might say. They have grown up on a 70-mile-long barrier island on the outer banks with flooding, wind, power outages, and weather woes.

Students at Cape Hatteras Secondary School of Coastal Studies are noticing, in particular, that storms and weather are becoming more frequent and more intense. Hurricane Dorian, which hit in September 2019, severely damaged parts of our island and one-third of our school. Students and staff missed nine days of instruction and then had to adapt to shared classrooms and no gymnasiums for months.

Two additional unnamed storms battered our coast in October and November, stranding residents on and off the island, due to Highway 12’s closure from ocean tide overwash. Subsequently, students and staff were also unable to attend school during those weather events.

Students at CHSSCS are organizing to understand these more frequent weather events and advocate for change. A group of 11th and 12th graders in Career and Technical Education Advanced Studies decided to conduct a study called “Student Perspectives on Coastal Change.”

The group concluded that a paper survey and focus groups would be the most effective way to collect data from the student body — 358 students in grades 6 through 12. Almost 70% of the student body completed and returned the survey.

From the survey, the group set out to learn general opinions on several topics regarding coastal change.

What They Found

Do students believe in climate change, and do they believe climate change is to blame for our increased storm activity and floods? Ninety-five percent of CHSSCS students surveyed said they believe in climate change, and 89% said that climate change was to blame for increased flooding on our island.

Coastal change increasingly confronts Hatteras Island residents with trouble spots like the one along NC 12, shown in the lead photo above after Hurricane Irene, as well as new inlets and flooding from storms such as Sandy (here). Both photos courtesy of NC DOT/CC BY 2.0.

How has increased flooding affected our students? Forty-two percent of those surveyed said that they had experienced flooding in their homes, and 24% had been displaced from their homes due to flooding.

Perhaps most importantly, students stated that storms and weather events cause them significant stress, and they worry about loss of home, money, or having to move away. Ninety-five percent of students believe that roads, bridges, and buildings will have to change in order for them to continue living here.

It is critical to understand how these weather events affect our students, because such concerns and stressors can impact attendance, behavior, and academic performance.

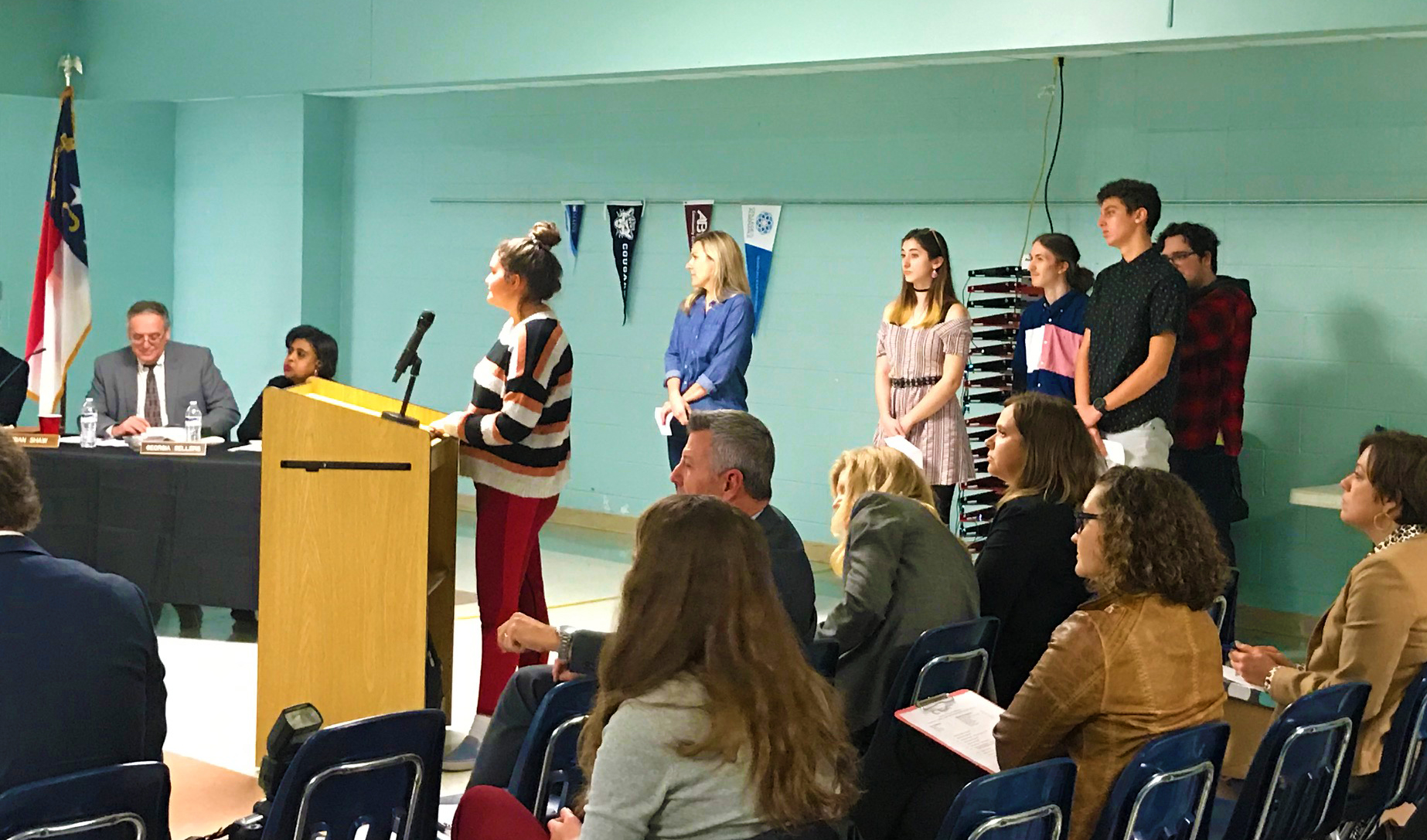

Island students decided to conduct their own study of how such changes are influencing their peers and presented the findings to the Dare County Board of Education.

Diving Deeper

The group administering the survey asked students who had responded whether they would be willing to participate in a focus group, and 28% agreed to do so. Using a variety of criteria, 15 students were chosen from grades 6 to 8 and grades 9 to 12 to participate.

In the focus group, students talked about how to combat problems resulting from the increase in flooding. They mentioned stricter building codes, including hurricane-proof dwellings, and added that they did not believe that anyone should be allowed to build on the ocean or sound fronts.

The group discussed Highway 12 and how it seems like lost dunes are constantly being pushed into place by heavy machinery. Students asked why sea oats were not being planted on the dunes anymore, since sea oats act as a stabilizing force.

During the conversation, students indicated certain thin strips of the island that frequently wash over and passionately advocated for allowing the ocean and sound to flow over such places on the island. They appreciated the value of natural inlets, which permit this water flow and presumably relieve stress on other parts of the island, where land would thicken and grow. Over natural inlets, the state could build small bridges or causeways, similar to the Florida Keys. Students also discussed federal and state storm assistance, as well as insurance claims for locals and non-resident homeowners.

How Long Will the Community Survive?

The final question: How long do you think our community has left to live on this island?

The middle school group had a bleak outlook, replying 20 years or less.

High school students did not think they would live to see the end of our island, responding not in my lifetime or around 100 years.

Students also said these views would influence their decisions on where to settle after high school. Most planned to move away from the island.

How does this impact the future workforce of Hatteras Island? What will happen to our community’s unique culture, traditions, and resilient spirit if those who were born and grew up here move away?

Questions remain. However, students also realized that they have the power to advocate as the next generation of change-makers on our island. They met up with a local county commissioner to address concerns and brainstorm solutions, and they already presented their findings to the Dare County Board of Education in February (above).

The impacts of climate change on our coast continue to be important for all those involved, and students may indeed be the driving force for adapting to climate change on Hatteras Island.

more from Coastwatch on climate change