By ANN GREEN with Photos By SCOTT D. TAYLOR

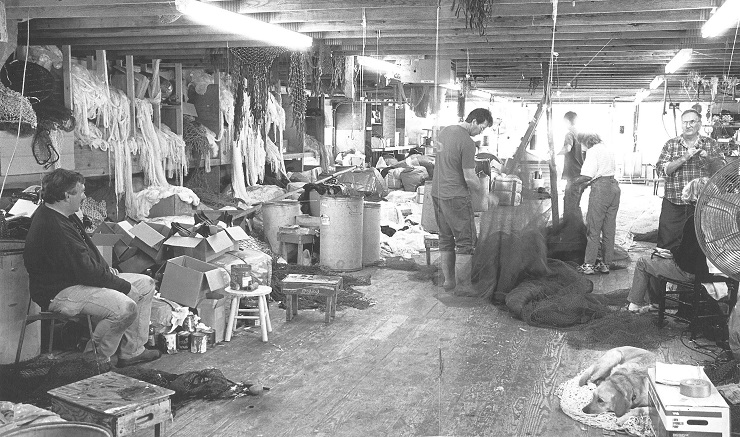

Inside a large building stacked with piles of webbing, Heidi Roberts whips a long needle in and out of a shrimp net so fast that her head bobs in a rhythmic fashion.

Her father, Roger Harris, and brother, Bubba Harris, work beside her stitching a 36-foot net for a shrimp trawl. In the back, another brother, Kerry Harris, hangs a net on a line for a crab trawl.

Each day, the family practices the time-honored craft of netmaking at Harris Net Shop in Atlantic. The work is tedious and precise, requiring the hand sewing of each net. Harris has callouses on his hands from more than 30 years of stitching nets.

“Netmaking is like woodcarving,” says Roger Harris, who carves duck decoys as a hobby. “It is a God-given talent. Not everyone understands it.”

The Harris family is in a profession that is highly specialized and slowly fading away. In North Carolina, there are about a half dozen full-time net shops. South Carolina and Georgia have even fewer.

“It is getting to be a lost art,” says Nicky Harvey of Harvey & Sons Net Shop in Davis, which boasts dozens of crab pots. “We used to stay busy doing nets year-round. Now half of our net business is gone. We are surviving by selling crab pots. Seventy-five percent of our business is crab pots.”

Most netmakers attribute the decreasing demand for nets to the growing number of state and federal regulations for commercial fishers. In North Carolina, there are specific requirements for fixed, gill, trawl, channel and pound nets and seines that are used to encircle fish and close all escape routes. Regulations also limit nets pulled by more than one boat and those used in long-haul fishing operations.

The regulations include mesh size, the diamond-shaped hole in the webbing. A net with large netting will hold only big fish. To catch a smaller fish, a smaller mesh is needed.

In 1992, North Carolina became the first state to require bycatch-reduction devices (BRDs) in shrimp trawls. The devices allow juvenile or small fish to escape via openings in the trawl nets, allowing fishers to keep mature fish and shrimp.

“Netting is going down the tubes like fishing,” says Heidi Roberts. “It looks like they are putting more and more restrictions on fishing.”

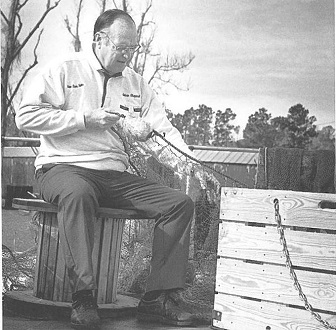

Not everyone’s business has declined because of the new regulations. Melvin Shepard of New River Nets in Sneads Ferry has diversified his business — selling outdoor wear as well as nets.

“The fishing industry is alive and well,” says Shepard. “In the 20 years that I have been in business, every year has been better than the year before. We take care of recreational and commercial fishermen.”

Recently, the debate over netting regulations has intensified between commercial fishers and sportsfishers. Texas has banned all gill nets. Louisiana restricts the use of gill nets, trammels or entanglement nets and seines in salt water, except for special permitted fishers during certain seasons. Florida has banned all gill nets and the use of monofilament — also used in fishing lines — for all except hand-held nets.

In North Carolina, the Wildlife Resources Commission is proposing a gill-net ban for inland waters.

In December, the National Marine Fisheries Service closed off part of Pamlico Sound to fishing with gill nets with a mesh greater than five inches. The area was shut off for a month because of the strandings of 74 sea turtles in the sound — 23 loggerheads, 12 green turtles and 39 endangered Kemp’s ridley sea turtles.

After the closing, the Coastal Conservation Association of North Carolina (CCA-NC), which has more than 8,000 members including some salt water recreational fishers, requested that the Marine Fisheries Commission establish a fisheries management plan for all gill nets in state waters.

“Under the Fisheries Reform Act, the state is required to manage fisheries by stock, region or gear,” says the association’s executive director Jay Kriss. “North Carolina hasn’t attempted to manage fishing gear. Gill nets are an effective commercial gear. We don’t want to ban nets. We want to manage how long nets are in the water and where they are set to secure bycatch reduction.” Now, he says, the bulk of gill nets are set out and left for days on end, often without being checked by fishers.

However, Jerry Schill of the N.C. Fisheries Association disagrees. “Gills nets are not indiscriminate. They can be very species- and size-selective, even more so than a hook and line.”

Marine Fisheries Commission Chairperson Jimmy Johnson says once the fishery management plans — which are species-specific and include management options for gill nets — are completed, it will be easier to look at a holistic gill-net plan.

“It would be difficult to do a gill-net plan for the whole state because our fisheries are so diverse,” he adds. “However, we could do a special gill-net plan for specific bodies of water, including the Pamlico and Albemarle sounds and the Pamlico and Neuse rivers.”

Net Traditions

Netmaking is as old as the fishing industry. Years ago, fishers would weave nets in their backyards.

One legend has it that Kerosene John in Southport made the first shrimp net, according to Harris.

In the early days, nets were made of cotton or other natural fibers. With the industrial revolution, cotton webbing became mechanized. Prior to this, fibers were spun to twine, and the twine was knotted into webbing by fishers.

“I remember fishing with my Dad,” says Shepard. “He would take a cotton or linen net and spread it out on two poles to dry out so it wouldn’t rot.”

With the invention of synthetic fibers, netmakers switched from cotton to nylon, polyethylene or spectra. The synthetic material comes in bales from the factory.

“New fabrics like spectra are high in strength and small in diameter,” says Steve Parrish, who runs a net shop with his wife, Sabrina, in Brunswick County. “The new fabric also allows you to pull nets faster through the water.”

Parrish learned the netmaking trade from his wife’s grandfather, Crawford Fulford.

“He encouraged me and shared his knowledge with me,” says Parrish. “He had done netmaking for 50 or 60 years.”

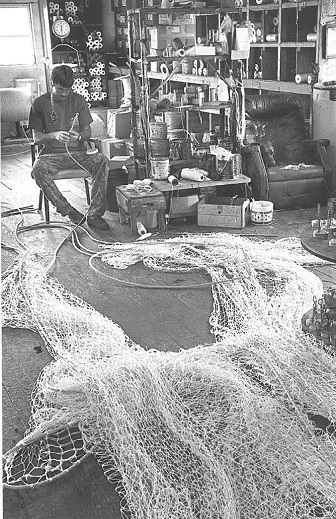

It took Parrish several years to perfect the craft. “It takes five to 10 years to become proficient and fast at netmaking.”

Grand Net Variety

Nets are tailored to differentiate between species of fish and shellfish. Shrimp nets can be cut and hung to distinguish between pink, white and brown shrimp.

The netmaker also needs to know the size of the boat, the horsepower of the boat’s engine, the number of nets and the water depth.

“There are as many ideas about making nets as there are fishermen,” says North Carolina Sea Grant fisheries specialist Bob Hines.

Most of the time, the fisher develops his specifications for the net. Then the netmaker makes the design.

Harris has dozens of patterns stuffed in a small tin box. “Some patterns are in my head, and some are in the box.” After designing the net, Harris cuts the net on a taper and sews it together. Fishers use one, two or four nets on shrimp trawls.

“Sewing a shrimp trawl is like a woman making a dress,” “Sewing a shrimp trawl is like a woman making a dress,” says Harris. “We’ve got yards and yards of cloth. People make all sizes of dresses. We make all sizes of nets.”

When the stitching is complete, Harris hangs the nets on a line inside. Then he puts the nets together in a funnel shape and adds a trap door, a turtle excluder device and a BRD.

Besides shrimp trawls, netmakers whip up a variety of nets for different species of fish — from gill nets to pound nets. Longer nets are hung outside on lines or between trees.

The nets vary in size from a small 3-foot try net used by shrimpers to test the catch in the water to gill nets thousands of feet long.

“When setting for flounder, it is not unusual for a fisherman to have set 2,000 to 3,000 yards of net,” says Shepard. “In hunting mullet, you might have a net that can be 20 feet deep by 500 yards long.”

A netmaker’s business is built on reputation. “Fishermen are on the water working and talking,” says North Carolina Sea Grant fisheries specialist Jim Bahen. ”They are always competing. They talk about the best nets like a truck driver talks about the best trucks. If a net is not catching well, the fisherman will be critical of the net shop.”

When a reputation is established, fishers from all over the country write or call a netmaker about buying nets.

“I make nets for people wherever there is shrimping — in Mexico, South America and from Virginia to Texas,” says Parrish.

However, he says even a high quality net won’t help an inexperienced fisher know what to catch. “You can have the best net, but you won’t catch any fish if the fisherman isn’t any good.”

Some netmakers say times have changed.

“My shops used to be lined with nets summer and winter for ocean-going boats,” says Harvey. ‘The business is getting worse and worse. If Roger Harris and I got out, don’t know what will happen. But I am going to keep fighting and fighting.”

NET KNOWLEDGE

By Ann Green

Most people think of a commercial fishing net as a simple mesh device that can be used to catch any type of fish. However, nets vary according to the type of fish caught. Here are some common nets used by fishers in North Carolina waters.

Gill net

is versatile and can be used to catch a variety of fish — from trout to hake and flounder. These nets have openings large enough to allow a fish’s head to pass but not its body. When the fish tries to back out of the webbing, it is caught behind the gills.

Pound net

is intricate and has three sections: the leader, the heart and the pound. The leader is a long expanse of webbing that extends to the shore and bars fish from swimming downstream, directing them toward the heart — the funnel that channels fish into the pound. Also called a trap, a pound is a webbed box with no top and no means of escape for the shad, herring or flounder that swim into its midst.

Seine

is used to encircle fish and close an escape routes. The circle of net is pulled smaller and smaller until the trapped fish are concentrated.

Trawl

is a flattened, cone-shaped net that is lowered to the ocean or sound bottom and dragged along by the power of a boat. Shellfish or fish are swept into the mouth of the net and pile up at the cod or back end. In North Carolina, a bycatch-reduction device and a turtle excluder are required.

Fishers may tow from one to four trawls behind their vessels. Periodically, the trawl is winched aboard the board to empty the catch. Trawls can be rigged to catch shrimp, crabs, flounder, spot, croaker and squid.

This article was published in the Spring 2000 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.