By KATIE MOSHER with Photos By MICHAEL HALMINSKI

Mention shipwrecks and treasures along the North Carolina coast, and most folks think of gold coins or ship’s cannons.

But near Rodanthe, one treasure has more to do with the lives saved in shipwrecks off Cape Hatteras than with the bounty lost to the sea.

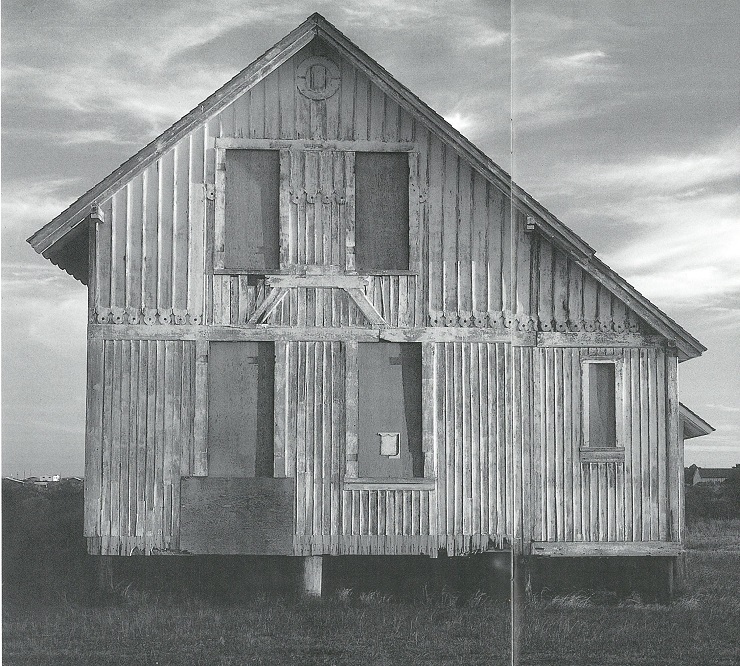

Built in 1974, a simple yet elegant wooden building has been considered a storage barn for most of this century. It sits in the shadows of a larger lifesaving station that operated from 1911 until 1954.

The larger building has drawn thousands of tourists since it opened as a museum in 1982. But as renovations continued on the site, preservationists realized the former boat shed was in fact, the hidden treasure.

“This is going to be the centerpiece,” says Michael Halminski, former president of the Chicamacomico Historical Association as he walks through the building that stands 43 feet long, 19 feet wide, with a two-story boat area, living space and a third story for storage.

“It was the first of seven lifesaving stations put on the Outer Banks,” he says of the complex of buildings that carries the Native American name for the area.

Ken Wenberg says the restoration is a one-man project. “I work by myself. There is only one restorer,” he says. “But I get a lot of advice — for free,” he adds with a chuckle.

A skilled craftsman, Wenberg stays true to the original construction style, using wooden pegs rather than metal nails in the building’s frame.

But the site’s treasures are not limited to the building. Wenberg also is keen to preserve the stories of the architect and the lifesaving crews — including ancestors of his wife, Jackie.

This research takes him well beyond his woodwright skills. To find the original records of the Outer Banks stations, he shows the tenacity of a gumshoe detective and the enthusiasm of a revival preacher.

While he works alone inside the building, Wenberg uses faxes, the Internet and e-mail to enlist the aid of dozens of professional and amateur historians and archivists to track the records. Working from homes and offices, they spend countless hours scouring libraries and archives to solve mysteries of the missing maritime records.

Their combined success goes beyond the history of this single Outer Banks landmark. They are providing missing pieces in the legacy of the U.S. Lifesaving Service and other federal agencies in the 1800s.

“Go back in the National Archives or the Library of Congress, you will find virtually nothing,” Wenberg says. “You can find lots of things after 1915.”

EARLY LIFESAVERS

Before the U.S. Coast Guard, there was the U.S. Lifesaving Service. Wenberg’s research goes back even further to the Revenue Cutter Service and local humane societies that rescued the crews of ships lost along the dangerous shoals near the Outer Banks.

In the late 1840s, the federal government agreed to form a lifesaving service, “but it never got off the ground,” Wenberg explains. For the first two decades, the service’s activities were focused in New York, New Jersey and the Great Lakes.

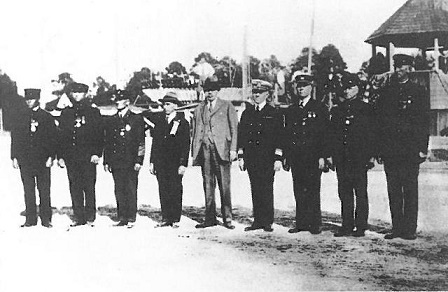

The lifesavers who participated in the “Mirlo” rescue are presented American Grand Crosses of Honor in Manteo, July 23, 1930. Photo courtesy of NC Archives and History.

The Civil War left the efforts stalled, but by 1871, there were 71 “red houses,” also known as houses of refuge. The plain buildings looked more like barns than stations.

In the 1870s, as shipping activity along the North Carolina coast increased, Sumner Kimball was given the helm of the U.S. Lifesaving Service. New stations were ordered along the East Coast, including areas along the Outer Banks that already were earning the title “Graveyard of the Atlantic.”

The 1874 plans offered a building much more detailed than a barn. Eventually, they were used for about two dozen stations along the East Coast. Seven were along North Carolina’s Outer Banks Chicamacomico, Little Kinnakeet, Bodie Island, Nags Head, Kitty Hawk, Caffey’s Inlet and Currituck Beach, also known as Jones Hill.

Before he started the Chicamacomico station, builder James Boyle had worked on a station in Little Kinnakeet, also on Hatteras Island. “The marine revenue cutter inspector made him tear it down because it did not conform to the military plans,” Wenberg explains. “There were multiple sets of plans floating around.”

Boyle was discharged before the Kinnakeet station was rebuilt as a variation of the Chicamacomico design. That building now belongs to the National Park Service, but it has not had the attention of its sister station.

Over the years, the other 1874 design stations have met a variety of fates. One was lost to the roaring sea. Several became private residences or offices.

The Kitty Hawk station has been moved twice and now sits across the road as the Black Pelican restaurant. The building has it’s own footnote in history — it is where the Wright Brothers came to send a telegram announcing their first flight.

And the building, which now has an addition, may have a ghost. “I have seen a wine glass move two feet down the bar,” says Tommy Matthews, general manager of the restaurant.

The original Caffey’s Inlet station, built in 1874, burned. But its replacement, built in 1899, still stands in its original location in Duck. Now it serves as the restaurant at the Sanderling Inn.

A TOWN’S LIFEBLOOD

For generations, the Chicamacomico facilities were the heart of the community. Town leaders were those who made lifesaving their career, such as Zion S. Midgett, who was in the service for 30 years.

“He had five sons, four were in the Coast Guard,” says his granddaughter, Jackie Wenberg. “Most everybody was in the Coast Guard.”

John Allen Midgett is pictured some years after the “Mirlo” rescue. Photo courtesy of NC Archives and History.

In particular, the Chicamacomico lifesavers were known for daring rescues. 1n 1891, they were credited with saving seven members of the Strathairly, which had been lost in wind, fog and high surf. In 1898, they rescued the crew of the schooner Fessenden.

In 1899, they were able to save the entire crew of the Mini Bergen by using the Lyle gun and “breeches buoys.”

“If the surf was dangerously high or the vessel wrecked close to shore, a Lyle gun was used,” explains a history prepared by the Chicamacomico association.

The gun was actually a bronze cannon mounted on a w0oden carriage. It could fire a projectile and line 450 yards. “The surfmen on shore fired the projectile over the wreck, where the crew secured it to the wreck,” the report adds. Once the crew was able to secure a rope, known as a hawser, the rescue could begin.

“Underneath the hawser rode the rescue device known as the breeches buoy, a life ring with trouser legs. One victim at a time could be pulled ashore in the breeches buoy by the rescuers on the beach.”

Such rescues are recreated on Thursdays throughout the summer as members of the historical association demonstrate the lifesaving drills. The rescues are a delight to tourists, who also view artifacts including a ship’s door, a life car, uniforms and the boat used in the station’s most famous rescue — the Mirlo in 1918.

Legends honor the surfmen who, led by Captain John Allen Midgett, saved the 42 members of the Mirlo, a British tanker that had hit a World War I German mine.

The rescue, which came in the face of fire and turbulent seas, brought honors from the British and United States governments. “They received the American Grand Cross of Honor — six of the 11 ever presented,” Ken Wenberg says.

When Jackie Wenberg was young, the focus of the Chicamacomico station was the shingled building built in 1911. “When I was a child, this building was the boathouse out on the beach,” she says of the original station.

ARCHITECTURAL QUESTIONS

The 1874 building has been moved several times — as its original location would now be about 1,800 feet into the ocean waters. The building is now about three-quarters of a mile south and 2,900 feet west of the original site, with its grand doors offering quick access to the sea.

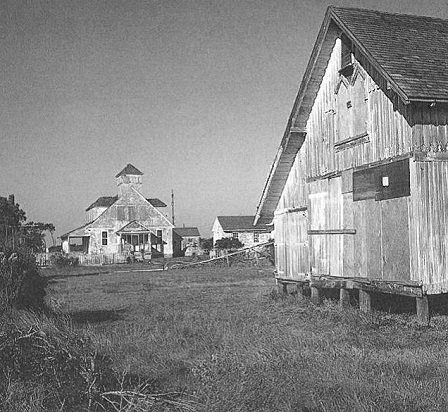

This east view of the old station in 1983 also shows the 1911 station.

Many of the more ornate aspects had been removed and destroyed. The eave supports were protected when a shed was added in 1889. “Nobody had looked above the shed ceiling since 1889,” Ken Wenberg says.

Once the eave supports were found, Wenberg could see the original paint color. “To a restorer, this is like Christmas,” he says.

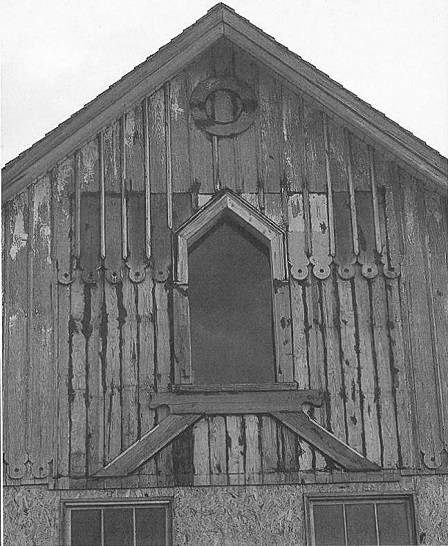

Tracing the history of the station’s design and construction has been a challenge for Wenberg, who points to the eaves, which originally had ornate trim that had been long forgotten.

“This raised an entirely new set of questions: Who is the architect and why is it so ornate?” he says.

After more than 200 hours of research, Wenberg tracked down the original plans for the building. They had been saved almost by accident when a U.S. Coast Guard historian from Charleston pulled them aside when files were being cleaned out.

“These eight pages are the entire verbiage for the labor and materials for this building,” Wenberg says.

“I can’t believe they would throw these things away,” Halminski adds.

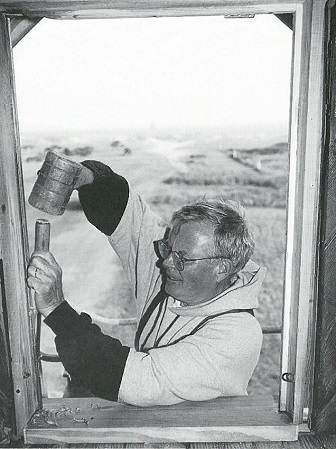

Restoration work progresses.

The architect, Frances W. Chandler, was a graduate of the Paris Architectural Institute. He toured Europe, sketching favorite buildings from gothic and renaissance styles.

“What we feel he did was that he took what was in his heart — the things that he had sketched in Europe — and put the composite into a building,” Wenberg says.

After nearly 250 more hours, and with the assistance of 57 other people, Wenberg tracked down Chandler’s sketchbooks in the personal library of E.I. DuPont. “People got excited. Here we have something extremely unusual,” he says.

“This is the only one of the first 23 still intact,” Wenberg says. “When we get this done, it will be one of a kind.”

The same design was used for the original stations that dotted the coast from Cross Island, Maine, to the Outer Banks, but most have had remodeling and additions.

In Chandler’s sketchbooks, Wenberg found designs repeated in the Chicamacomico building, such as windows from a church in northwest France that was built in the 1500s.

What really clinched it for Wenberg was the drawing of a medieval building in Cannes, France, that was built in 1032. The board-and-batten style with gothic windows was just the same. “Bang — it jumps out at you,” he says.

Although other construction styles were available in the 1870s, the building features a post-and-lintel style. “Everything is pegged with wooden pegs — not a nail in the frame,” Wenberg says.

“This building was knocked around by storms, off its foundation three times, and moved several times, but remained intact,” he adds.

“The internal construction style dates to medieval times.”

MISSING RECORDS

Wenberg is fascinated not only by the architecture and craftsmanship in the building, but also by the history of the lifesaving crews. As he and others spent hours searching for records, he soon began to realize that files were not only missing from the U.S. Lifesaving Service, but also from other federal agencies of the time period.

“I diverted my attention to find out why part of the history of our country was missing,” he says. To his amazement, he found out that in 1970, the federal government sold many uncataloged U.S. Treasury Department records from 1795 to 1914.

Ken Wenberg works on a window opening.

“I considered it finding the Mother Lode,” he said of the records that were sold to a foundation for $260,000. “It seems strange that they sold these.”

But then again, maybe the sale is a reflection of the times. “We are a throwaway society. We don’t do a good job of preserving history in this country,” Wenberg says.

The small foundation had microfilmed and cataloged the records, but had not had outside requests to review the documents. “I was the first one to ask,” Wenberg says. “They let me copy the first book ever printed for the lifesaving service.”

The foundation is working with Wenberg and the Chicamacomico Historical Association, but at this time it does not have the staff to handle a large number of research requests.

In the meantime, Wenberg and his team tracked down the surfmen’s logs in the Atlanta branch of the National Archives. Those logs should give firsthand descriptions of the lifesaving efforts.

“The logs are now available,” Wenberg says. “I am anxious to get somebody down there. It will lead to a lot of things that we are guessing at.”

The team also has found records of major universities’ libraries. “For the first time in history, we have the availability of knowing every shipwreck — how many lives were lost or saved, how much cargo was lost or saved,” he says.

“We can track down the names of the keepers and the superintendents and the types of buildings and architecture. We can track down the various types of boats used,” he says.

The research efforts will continue alongside the restoration work on the building. Hurricanes Dennis, Floyd and Irene slowed work last fall, but Wenberg expects to have the exterior renovation completed by this spring. The interior work will take another year.

The Chicamacomico Historical Association also plans to furnish the building — and hopes to utilize plans for the original boat and car.

“My hope is that people can view the building as it was in 1874,” Wenberg says. “When people come in, they can look at history.”

Yet, once the architectural renovations are complete, there will be tasks ahead for Wenberg.

He dreams of a reunion one day for the families of those who were saved by the Chicamacomico surfmen.

This article was published in the Winter 2000 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.