By PAM SMITH with Photos By SCOTT D. TAYLOR

The day defines summer, in North Carolina — hot and humid.

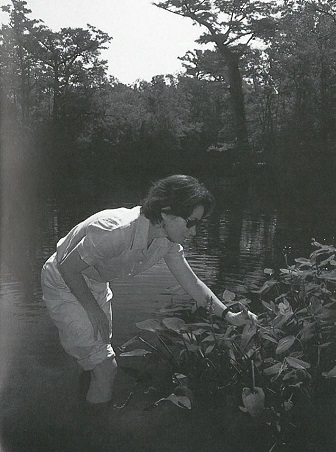

Camilla Herlevich happily slips off her shoes, rolls up her neatly pressed chinos, and wades into Town Creek. Knee-deep in the refreshing water, she’s in her element.

Herlevich, founder and executive director of the North Carolina Coastal Land Trust (NCCLT), often paddles the pristine black water system that winds through surprisingly undisturbed upland bluffs, swamp forests and marshes. Town Creek, which empties into the Cape Fear River near bustling Wilmington, is popular among paddlers, anglers and naturalists.

Conserving land along the Town Creek corridor protects natural resources and early settlement sites, including Old Town and Charles Town.

And for good reason. Town Creek ranks as a nationally significant natural heritage site. The North Carolina Heritage Program considers it the best remaining example of the Lower Cape Fear River’s original freshwater fauna.

Herlevich notes that colonial explorer and surveyor John Lawson, in journals penned in the early 1700s, describes many features still seen today in the area.

That it remains unspoiled in the face of explosive development in the surrounding Brunswick County landscape, is remarkable. Even more remarkable is that there’s a good chance that much of what Herlevich calls “this wild and wonderful place” will stay that way.

While the NCCLT aims to preserve open space throughout the coastal plain, it places special emphasis on river corridors.

Three years ago, the NCCLT launched the Town Creek/Lower Cape Fear Initiative to protect the river corridor from its headwaters to the Cape Fear. With more than 7,100 acres already protected by agreements Herlevich and her staff have negotiated with landowners — the goal is well within reach.

The focus makes environmental sense. Natural shoreline buffers, also called riparian zones, enhance water quality for drinking, fish nurseries and recreation by filtering pollution and sediment runoff. They also provide food and shelter for wildlife.

“Historically and culturally, rivers are where everything comes together. Our earliest communities were situated on rivers, which were arteries of commerce,” Herlevich adds.

A NATIONAL TREND

Walter Clark, North Carolina Sea Grant coastal policy and law specialist, says the efforts fit into a larger picture.

“The North Carolina Coastal Land Trust success story is being repeated across the state and nation.”

Land trusts and conservancies are nonprofit organizations that work with landowners interested in conserving their property.

“Land trusts can help individuals, families or businesses find the right tools to protect natural and cultural resources for generations to come,” Clark says.

The treeline in the distance is a natural buffer on this working farm along Town Creek — soon to be part of the N.C. Coastal Land Trust preservation mosaic.

In North Carolina, the preservation movement was boosted in 2000 with former Gov. James B. Hunt’s Million Acre Plan. It recognizes the need to protect open space, forests, farmland, streams, rivers, lakes, estuaries, sounds and coastal waters to balance growth and development. The challenge is to have one million acres protected by 2010.

Clark notes that federal and state tax incentives are enticing land owners to donate what are called conservation easements to private nonprofit land trusts or conservancies. These legal agreements limit a property’s use in order to protect its conservation value. In this respect, conservation easements can ensure that future land use maintains the family tradition.

More good news for the individual property owner: Easements come with reductions in property and estate taxes — benefits that lessen the pressures on landowners to sell off farms, forests or estates rapidly rising in value.

On the federal level, the Farm and Ranch Protection Act of 1998 provides an exclusion from the estate tax of up to 40 percent of the value of the land covered by a conservation easement.

In addition to these tax incentives for donated easements, there are other new financial sources for purchased conservation easements. State programs in North Carolina include the Clean Water Management Trust Fund and the Farmland Preservation Program.

The Farmland Protection Program is a federal source of grants for state or local governments or land trusts. The program is administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to purchase conservation easements on farmland.

Also, the Forest Legacy Program was established in 1990 by the USDA to protect environmentally important forest areas that are threatened by conversion to non-forest uses — with a specific goal to protect important scenic, cultural, fish, wildlife and recreational resources, riparian areas, and other ecological values.

The program authorizes the U.S. Forest Service to provide grants to state forestry agencies for the purchase of lands that specifically meet the mission of the program.

To date, the nation’s 1,200-plus land trusts have helped protect more than 4.7 million acres, according to the Land Trust Alliance, a national resource center based in Washington, D.C.

A MOSAIC OF SUCCESS

Piece by piece, Herlevich says, the Town Creek preservation mosaic is coming together as a result of many of these incentive and grant programs. Figured in this emerging picture of success are Old Town and Pleasant Oaks — family-held plantations steeped in history and totaling nearly 3,000 acres. A recent anonymous land donation adds another 3,000 acres to inventory.

Camilla Herlevich says Town Creek, a nationally significant natural heritage site, is popular among paddlers, anglers and nature lovers.

Soon, a family-owned working farm — with a wide, forested riparian buffer along Town Creek — will add another 268 acres to the tally.

Where large tracts of land under family ownership can be identified, negotiating to acquire conservation easements is rather straightforward, Herlevich says.

It takes different strategies and tools to broker a more complex agreement such as the one with International Paper. With Clean Water Management Trust Fund monies from the state, NCCLT is acquiring conservation easements along Town Creek — about 725 acres.

In addition, the U.S. Forest Service awarded the N.C. Division of Forest Resources $1.4 million to purchase development rights on 560 acres of timberlands in the uplands. This was the first Forest Legacy Program grant awarded in North Carolina.

These agreements prohibit timbering on the sensitive riparian acreage. International Paper may pursue traditional timbering on the less environmentally critical upland acres.

Herlevich says NCCLT has found a niche with its focus on the coastal plain and the use of nonregulatory tools for environmental protection — land acquisition and conservation education. Beyond the Town Creek initiative, the group has preserved more than 10,000 acres of marshes, creeks, plantations, islands and gardens through conservation easements and outright acquisitions.

The group also assisted state parks’ officials and the National Audubon Society in negotiations with landowners to purchase Jots on Lea Island, an undeveloped barrier island that is a nesting ground for dozens of migrating and resident water birds.

It partners with The Nature Conservancy on projects along the South and Black rivers. And, it helped establish the Tar River Land Conservancy, which will focus on protecting natural and cultural resources surrounding the Upper Tar River Basin. NCCLT also helped organize the Smith Island Land Trust, which works to protect land at Bald Head Island.

Clark believes the credibility of land trusts and conservancies is reinforced by mutual efforts to increase the public’s understanding of the stresses on coastal resources by sharing science and information about land stewardship.

“Land trusts and conservancies are important bridges for maintaining rights of private property ownership,” Clark says.

“Regulations put restrictions on ways land could be used. Land trusts offer landowners options for protecting the environmental and cultural value of their property.”

For further information about The North Carolina Coastal Land Trust, contact Camilla Herlevich at camillah@wilmington.net. For information about land trust efforts in North Carolina, visit the Conservation Trust for North Carolina on the Web at www.ctnc.org.

This article was published in the Autumn 2001 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.