By ANN GREEN with Photos By SCOTT D. TAYLOR

It is a quiet, cloudy day on the Pamlico River in downtown Washington. There are no sounds except for the lapping of paddles through the mossy green water.

In eastern North Carolina, ecotourism — which includes paddling and other outdoor activities — has boosted local economies.

More than a dozen paddlers create a spectrum of color as they stroke slowly in red, green and yellow kayaks and canoes toward an old railroad bridge.

‘The bridge is still in use,” says North Carolina Estuarium administrator Blount Rumley, who is following the paddlers in a pontoon boat. ‘Toe railroad uses the tracks a couple times a day.”

After passing the bridge, the paddlers follow one another along the south shoreline where the Tar and Pamlico rivers meet. The area is uninhabited and covered with cypress trees, cattails and marsh. The only sign of wildlife is the whistling of red-winged blackbirds.

”When the sun is out, this area comes alive,” says Rumley. “You can follow the shoreline and see snakes, turtles and other wildlife.”

Geese fly overhead as paddlers continue down the shoreline until they reach Castle Island bordered by old dock pilings. During the Civil War, oyster shells were processed into lime at Castle Island for agricultural use, says Rumley. “One of the buildings was a kiln for baking shells,” he adds. ‘Toe island was a safe location because of the fire hazards.”

The wide, calm waters of the Pamlico River provide a picturesque and easy water trail for inexperienced paddlers. ‘This is the first time I have ever kayaked,” says Robert Maxwell. “I didn’t realize how stable kayaks are. It is so much fun to be with my granddaughter. The river is so calm.”

The smooth, easy trail also provides a pleasant journey for experienced paddlers like Carl Rabe. Dressed in a sleek, black wetsuit, Rabe is loaded with paddling safety equipment, including a strobe light, whistle, cell phone, reflector and tow rope.

‘The Washington area is a good place to paddle because it provides access points for paddlers,” says Rabe. “Sometimes it is not easy to find a place to put in and also have parking. A lot of marinas just cater to big boats.”

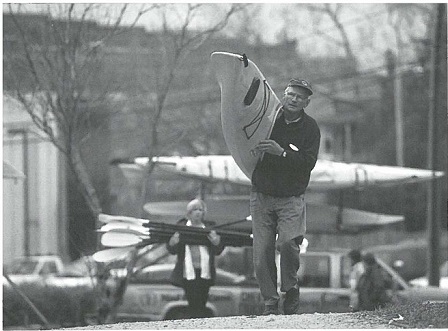

Kayakers get ready for the Coastal Plain Waters 2001 field day. Many styles of kayaks are light enough to carry to launch sites.

Both Maxwell and Rabe are participants in Coastal Plain Waters 2001 — a three-day event promoting coastal paddling trails and a new trails map available in print or online.

The color map, which divides the coast into eight regions, includes more than 1,200 miles of navigable water trails east ofl-95, including the brackish marshes on the Alligator River and Lake Phelps with its towering bald cypress trees. Each paddle trail entry includes a map, difficulty levels and designated points where paddlers can put in and take out as well as mile markers.

“North Carolina offers once-in-a lifetime opportunities for paddlers,” says Lundie Spence, North Carolina Sea Grant marine education specialist. “Paddlers can enjoy a variety of activities -from birding and fishing to exploring historic sites and diverse plants and wildlife. The map and the companion Web site are designed to assist kayak and canoe users in planning adventures on North Carolina’s coastal plain rivers, creeks and estuarine waters.”

The map also can be used as a marketing tool for local communities.

“To have a guidebook or map available gives people an instant vacation,” says Karen Stimpson, executive director of the Maine Island Trail Association and a participant in the North Carolina paddling event. “People will go where it is easier for them to get to.”

Sea Grant Survey

In eastern North Carolina, ecotourism — which includes paddling and other outdoor activities — has boosted local economies.

Each year, paddlers contribute more than $148 million to North Carolina’s coastal economy, according to a survey conducted by North Carolina Sea Grant extension director Jack Thigpen. Nearly a third of these paddlers have an annual household income of more than $90,000, and more than two-thirds are professionals or managers, the survey reports.

“Coastal kayak and canoe paddlers can have a positive impact on our rural waterfront communities,” says Thigpen. “The survey helps us understand what these paddlers want so that local businesses can meet their needs. We also are working to ensure that any conflicts arising from the increased use of our waters are minimized.”

At Kitty Hawk Sports, paddling sports have boomed, says Pam Malec, water division manager. ”It is a safe sport,” she adds. ”We take more than 6,000 people a year on trips.”

North Carolina isn’t the only state where paddlers are hitting sounds, creeks and rivers.

A group of experienced kayakers navigate the scenic water trails along Chocowinity Bay near Washington in Beaufort County.

”Recreational kayaking, which includes touring in flat water, has grown 17 to 28 percent a year,” says American Canoe Association (ACA) Conservation Director David Jenkins. ‘This is based on figures from small paddling shops.”

Trail association directors and others attribute the increased interest in paddling to a number of reasons, including affordability.

“If you look at boats for kayaking, there is a whole line of recreational boats —from high-tech composites and roto-molded to less sophisticated and inexpensive,” says Al Staats, executive director of North American Water Trails Inc. “Anybody can throw a boat on a car and use it.”

For families, kayaking and canoeing have become popular outings.

“It is one of the fastest-growing family sports,” says Andy Zimmerman, founder and board member of Confluence Watersports Co. near High Point. ”You can experience the magic of paddling together and have an everyday experience. An afternoon of paddling will soothe your soul.”

In addition, water trails are wonderful outdoor classrooms, says Matt Angotti, environmental educator with the North Carolina Coastal Federation.

“It is empowering for kids to spend a day on the water and learn how to canoe,” says Angotti, who works with 5th to 12th graders from across the state and from diverse backgrounds. “One group from Fayetteville got to see dolphins for the first time on a canoe trip to Hammocks Beach State Park.”

Another group from Apex got to see wetlands as they paddled through Hoop Pole Creek in Atlantic Beach. ‘They learned about the values and functions of wetlands as they canoed in some of the cleanest water in Bogue Sound,” he says.

‘Through these experiences, we are trying to inspire teachers and students to become motivated, active stewards of North Carolina’s coastal estuaries and rivers.”

As paddlers become more aware of the environment, some voice concerns about water quality. The 50,000-member ACA argues for clean water enforcement across the country.

In 1998, the ACA sued Murphy Family Farms, which has since been bought by Smithfield Foods, for the illegal discharge of hog waste into a tributary of the Black River and the failure to obtain a National Pollution Discharge Elimination Permit for the facility.

The court ordered the farm to get a permit ‘This is a landmark case establishing that hog farms have to get a Clean Water Act discharge permit,” says David Bookbinder, ACA general counsel. ‘This decision will help control hog waste from thousands of giant hog farms in North Carolina and other states as permits are issued. The less hog waste in the water, the happier canoers are.”

Smithfield Foods officials declined to comment on the lawsuit.

Paddling Ancient Sport

Water trails have been around North Carolina for thousands of years. During the early years, Native Americans and explorers used the state’s streams, lakes and coastal waters for transportation. In 1985, park officials at Pettigrew State Park found dugout canoes in Lake Phelps and estimated Native Americans used the canoes more than 4,000 years ago.

Author Nathaniel Bishop’s yearlong canoe trip in the late 1800s along the eastern seaboard and the Outer Banks has become legendary.

In Voyage of the Paper Canoe, which was recently reprinted by Coastal Carolina Press, Bishop details his 2,500-mile journey in his custom-built, 58-pound canoe. He also gives a glimpse into 19th century coastal life while chronicling his stay at the Bodie Lighthouse on Oregon Inlet.

Kayakers enjoy picturesque scenery, including towering cypress trees, along paddle trails in coastal waters.

“Having secreted my canoe in the coarse grass of the lowland, I trudged, with my letter in hand, over the sands to the house of the lightkeeper, Captain Hatzel, who received me cordially; and after recording in his log-book the circumstances and date of my arrival, conducted me into a comfortable room, which was warmed by a cheerful fire, and lighted up by the smiles of his most orderly wife,” he wrote in the book.

”Everything showed discipline and neatness, both in the house and the lighttower. The whitest of cloths was spread upon the table, and covered with a well-cooked meal; then the father, mother, and two sons, with the stranger within their gates, thanked the Giver of good gifts for his mercies.”

Bishop’s voyage was unusual for that era. Until the middle of the 20th century, few people paddled the coastal water trails solely for recreation.

“My dad was an original old-time canoeist,” says Rumley. ”In 1932, he and a friend paddled from Washington to Kitty Hawk and then down to Ocracoke. That area was very primitive then. They slept under the canoe and ate cans of beans.”

In the later half of the 20th century, people turned to the water again for recreation. However, by then thousands of miles of river, creek and estuarine shoreline were privately owned and closed to the public.

”When I started paddling in the 1950s and 1960s, I took a boat and launched it anywhere,” says Staats. “I did not have any support. It would get dark, and I would realize that I did not have a place to beach or put up a tent.”

As the country’s population began to increase and access to waterways became more difficult, more people began to value the vast water heritage and its potential for recreation.

In 1966, Maine established the 92-mile Allagash Wilderness Waterway. Two decades later, the state of Maine and a nonprofit group teamed up to establish the Maine Island Trail along some 325 miles of coastline and using more than 30 state-owned wild islands as overnight stopovers.

Later, other states also developed extensive waterway trails, including Washington’s Cascadia Marine Trail and New York’s Hudson River.

North Carolina Efforts

During the past several years, the N.C. Division of Parks and Recreation has been assisting groups and organizations in developing paddling trails.

By early 1999, more than 12 groups had developed 141 individual trails that stretch more than 1,200 miles in 23 eastern North Carolina counties. That same year, several groups joined together to expand the coastal paddling trails system through the North Carolina Coastal Paddling Initiative.

Many of North Carolina’s navigable water trails are marked with signs that help paddlers find their way.

The initiative was a cooperative effort between Confluence Watersports Co., North Carolina Sea Grant, Partnership for the Sounds, Division of Parks and Recreation, North Carolina State University Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism Management, Mid-East Resource Conservation and Development Council Inc., Progress Energy and the North Carolina Estuarium.

Tom Potter, who helped develop the trails system, says this is just the beginning of marked water trails in the Division of Parks and Recreation.

‘There are probably 800 to l,000 miles of trails under development,” says Potter, former regional trails specialist and now manager of the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program at the N.C. Division of Soil and Water Conservation.

For example, the Crystal Coastal Canoe and Kayak Club is developing more than 50 miles of paddling trails in western Carteret County on the White Oak River, including Bear Island and Swansboro. The trails will be part of the N.C. Coastal Plain Paddle Trails Guide on the Web. A separate map will be available at tourist locations and kayak suppliers in Carteret County, according to John Davis, former club president.

‘The White Oak River is such a prize,” says Davis. “It has five distinct ecotypes. There are sections with hardwoods, cypress, red cedar and a marsh. For part of the way, the trees tower over the stream. There are even some rapids. This is unbelievable for a river on the coastal plain.”

With the large number of water trails in ea5tem North Carolina, the state has a lot of potential, says Zimmerman. ”We hope paddling trails become as common in this state as hiking or bike trails.”

To view or order the coastal plain paddling trails map, visit the Web: www.ncsu.edu/paddletrails. Paddling enthusiasts also can join a new organization, The North Carolina Paddle Trails Association, which is assisting weal paddling clubs in establishing and maintaining paddling trails. For more information, contact Ward Swann, 6233 Sentry Oaks Dr., Wilmington, NC 28409 or e-mail: ward_swann@yahoo.com.

This article was published in the Autumn 2001 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.