By ANN GREEN with Photos By SCOTT D. TAYLOR

The R/V Perkins was the home for the ECU underwater archaeology field school in Edenton.

At the mouth of Pembroke Creek in downtown Edenton, several scuba divers bob up and down in dark, chocolate-colored water marked with tall white pipes.

Nearby, divers stand shoulder deep in water with waterproof drawing boards. A few feet away, a man in a black wetsuit wades near cypress knees and green lily pads so thick they create a shamrock pattern in the water.

“Stay off the baseline for a minute,” yells East Carolina University archaeologist Frank Cantelas. ”We need to use it to get a quick measurement.”

As one diver spreads out a tape measure over the water, Cantelas sketches in a 10- square-foot area — which represents the edge of an 18th century boat keel — on a drawing board.

“We are drawing a profile of a ship using the water surface as a line point,” says Cantelas, an ECU maritime studies professor.

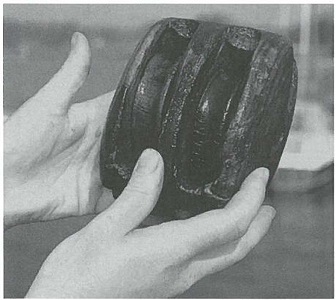

A block used to raise and lower sails is one of the artifacts found by students.

Pembroke Creek’s shallow and calm water — which is less than four feet deep near the shoreline — provides an ideal site for documenting and teaching graduate archaeology students, says Brad Rodgers, director of the summer field school at the ECU Maritime Studies Program.

“Everyone can stand up,” says Rodgers. “Because it is an 18th century wreck site, we are spending the whole time of the field school here. It is a very important site. There are only four 18th century sites that have been worked on in North Carolina. One of these is Blackbeard’s ship, the Queen Anne’s Revenge, off Beaufort.”

The archaeologists also gleaned other important details about the vessel.

“Through the preliminary work, we can say it is an ocean-going vessel approximately 85 feet long and 20 to 25 feet in width,” says Rodgers. Its tonnage — capacity in volume — was 200 to 300 tons, he adds.

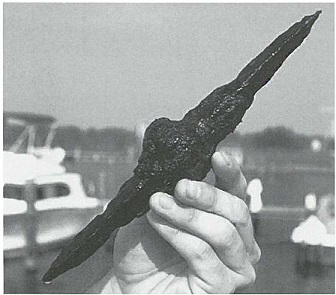

Students uncovered a black Spanish shot used to rip out a sailor burn a ship.

During the excavation, the students uncovered numerous artifacts from the muddy bottom of the Pembroke Creek, which is on the edge of the Albemarle Sound.

While standing on the ECU research vessel R/V Perkins, Cantelas shows four buckets of artifacts, including a dark black carpenter’s bevel used for marking angles and a wooden block used to set up rigging and raise sails.

The most unusual object is a black Spanish shot used to rip out a sail or burn a ship. “The Spanish shots were packed inside cannons and are fairly rare,” says Cantelas. ‘They were used by Sir Francis Drake in the late 1500s against Spanish vessels.” The shots still were being used in the colonial period when the ship was thought to be built.

By uncovering artifacts, Cantelas says they find out tidbits not usually recorded about people. ‘The artifacts help document the material culture of life on a ship,” he adds.

The Edenton excavation site is a “cool site” for graduate students, says Deborah Marx, a master’s student from San Francisco. “It helps having hands-on experience instead of just reading about shipwrecks. It helps with the ship construction and details.”

ARCHAEOLOGY PROGRAM UNIQUE

The ECU underwater archaeology program is one of only two graduate programs in the country offering a master’s degree and doctorate in underwater archaeology. Texas A&M also has a program.

“We are the only program that focuses on North American historic archaeology,” says Rodgers. “Our main focus is New World shipwrecks.”

The field school is part of a three-year maritime studies program. During the first year, students receive extensive scientific dive training, including low/zero visibility diving, underwater photography and archaeological recording and remote sensing.

“They make sure you are comfortable in the water,” says graduate student Kate Goodall.

“You have training to 100 feet However, most sites are not deeper than 30 feet.”

To give the students hands-on experience, they spend three weeks on a wreck site each summer.

The Edenton shipwreck was discovered accidentally during a storm by Gil Burroughs who lives in a home on the Edenton shoreline. “The water blew out, and Gil saw a wreck 100 feet from his house,” says Cantelas. “So we decided to check it out and use it for the field school location.”

The archaeologists think the ship was destroyed by fire but don’t know if the fire was intentional, says Rodgers. We think the boat carried small cannons, possibly two-pounders that were used to fight pirates,” he says.

SUMMER FIELD SCHOOL

The ECU students arrive at the site in early June. First, they outline the vessel’s shape with PVC pipes pushed into the creek bottom. They also place buoys around the part of the shipwreck that is not being investigated. Then each student is assigned a five-foot section of the ship to map out, but visibility is often near zero.

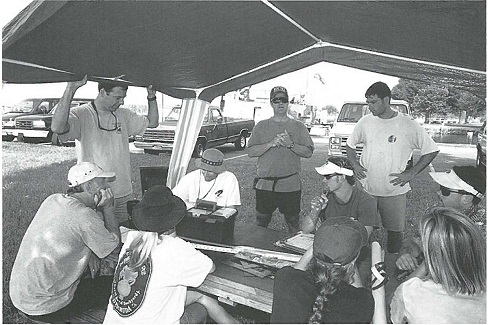

On a recent day, the students gather for the daily briefing under a blue and white tent next door to the historic Barker House. In front, giant cypress trees stand in the dark, black water. On the opposite side, cannons from the Sacred Heart of Jesus shipwreck — investigated by ECU students in 1994 — line the waterfront.

“We need to continue plotting and mapping the site,” says Rodgers while standing near a picnic table covered with a map and rulers. “Keith, you have a new assignment on the squares. You need to profile the stem section. I am still unconvinced that we found the rudder.”

Rodgers also tells the students to keep the chatter to a minimum. “It will be really crowded,” he says. ‘We will have people lined up and down the whole site.”

After the briefing, a couple of students stay with Rodgers and continue mapping their section on a large sheet of white paper. Others load their diving gear onto a pontoon boat at the public dock in Edenton or ride in a van to the opposite shoreline.

It takes Jess than five minutes for the pontoon boat to reach the middle of the sound and anchor.

One by one, each diver goes down a ladder into the water and swims over to the site that is near an Edenton shoreline filled with cedar trees and homes.

Marx is the last diver to leave the boat. As she straps a scuba tank on her back, she says she will be mapping a section on the boat’s frame with iron and wood fasteners.

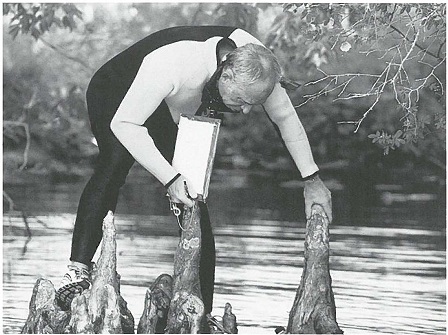

ECU graduate student Mike Overfield surveys an area of a shipwreck surrounded by cypress knees.

“I couldn’t see yesterday,” she says. “I had to feel everything. Even if you are the first one to go in the water in the morning, you can only see about a foot.”

As Marx jumps off the boat, she swims toward her buddy who is already working at the site. All the students work in pairs on a five-foot section of the port side of the boat. “Since the water is so shallow, the only danger is stepping on something,” says Marx, who is wearing tennis shoes to protect her feet.

‘There are a lot of metal pieces that are sharp.”

The group of 10 students and staff probe the site all morning. However, the only object pulled up was an oyster shell.

“Today, I saw a chain from logs and some planking,” says graduate student Mike Overfield. “I felt around and measured it from its position. I didn’t want to disturb the site any more than I needed to.”

At lunch, the students come in. Then a few go back out in the water in the afternoon. Others map their sections on a large roll of paper spread on the picnic table.

“I love this work because it always changes,” says Goodall. “One day you will be doing research. Another day you will be diving. And another time you will be writing.”

DIFFERENT WRECK SITES

Each year, the ECU archaeology program picks a different site for the field school. Last year, students mapped and surveyed wrecks around Castle Island, which was used for docking during the Civil War. The abandoned site on the Pamlico River across from downtown Washington has been the subject of two other field schools.

“So far 11 wrecks have been found,” wrote graduate student Heather Cain in Stem to Stern, the maritime program’s annual publication.

During the 200) field school, the students focused on several wrecks around Castle Island to see if Hurricane Floyd — which brought massive flooding, creating severe undercutting and erosion — had affected the island.

“When we relocated the wreck at Castle Island, we found it had migrated because of Hurricane Floyd,” says Rodgers. “The upriver face of the island had washed out the sand from 5 to 25 feet.”

ECU archaeologist Brad Rodgers gives a briefing to students on the Edenton waterfront.

Rodgers says the island will continue to move until it is re-stabilized.

“We don’t know how long it will take to re-stabilize,” he says. ‘When we go back to the site — which will be perhaps next summer — we will remap the island and see where it has moved and relocate the wreck sites. If the face of the island collapses, it will bury the wrecks in 20 feet of sand. We may never see them again.”

In 1999, ECU students documented the remains of the steamer Oregon, which was sunk in the Tar River near Tarboro in 1863 during a Union cavalry mid.

When they first investigated the site in June 1999, only one to two feet of water covered the site. Most of the vessel’s remains were exposed or lightly buried under three to four inches of sand.

The following fall, they examined the site again to see the back-to-back effects of hurricanes Dennis and Floyd. Matthew Lawrence, who is writing his master’s thesis on the Oregon, was relieved to find the shipwreck had not been destroyed.

Over the years, ECU students also have investigated sites from Bermuda to Hawaii and Lake Superior to the Caribbean.

Usually, they go outside of North Carolina for the fall field school.

During the mid-1990s, ECU students visited the World War II battleship Arizona in Hawaii.

“This is the ship that blows in the beginning of the movie Pearl Harbor,” says Rodgers. “Most relevant to the Japanese attack was our discovery of the U.S. PBY aircraft shot down while trying to engage the enemy. The plane sank in Kaneohe Bay.”

Each wreck is a “historic time capsule,” says Rodgers. “Each wreck has a story to tell,” he adds. “Wrecks tell how people lived and what material goods were manufactured and agricultural goods were grown there.”

‘SHIP THAT SAVED LAKE ERIE’

For three weeks, East Carolina University archaeology students and staff lived on a boat that is “almost an antique,” says ECU graduate student Matthew Lawrence.

The R/V Perkins, built in 1953 as an Army T-boat, is the students’ sleeping quarters and lab for summer field schools.

“The same person built the hull that built the landing craft used during D-Day in World War II,” says Lawrence.

Before becoming part of an ECU fleet, the Perkins was named the R/V Hydra and was known in the Great Lakes region as “the ship that saved Lake Erie.” Until 1997, the 65-foot laboratory cruiser monitored water quality for the Environmental Protection Agency.

As pollution and other factors led to a pronouncement that Lake Erie was “dead,” the Hydra was sent to identify the sources of pollution and conduct dissolved oxygen studies, says Timothy Runyan, director of ECU’s Maritime Studies Program.

After a larger EPA vessel replaced the ship, it languished at the dock in Bay City, Mich., until ECU acquired it.

In 1999, ECU archaeologists brought the ship to North Carolina — in a 12-day journey — across lakes Huron, Erie and Ontario, through the Erie Canal river docks, and down the Hudson River and Atlantic Ocean to a new home port in Washington.

“The Pamlico Sound was the roughest part of the trip,” says Runyan. “Short, choppy waves were driven by a 35-knot ocean gale.”

Since acquiring the vessel, ECU has used it for nearshore and offshore underwater research work. “We carried all our research equipment, food and 10 students from Washington to Edenton,” says Brad Rodgers, director of ECU’s Maritime Studies Program’s field school.

During this year’s field school, the vessel was used to store the recovered artifacts, scuba tanks and gear. Students also prepared food in the galley and slept in bunk beds. “The students stayed on here for three weeks and had a great time learning to work as a team,” says Rodgers.

The vessel also provides a stem dive platform and a Dunbar crane capable of lifting more than five tons.

“You must have a platform in the sea to do underwater archaeology and marine science,” says Runyan. “The R/V Perkins is a solid, proven vessel.”

This article was published in the Autumn 2001 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.