By PAM SMITH with Photos By MICHAEL HALMINSKI

A dissonant chorus of alarm clocks pierces the predawn silence and bounces across the dark surface of the pond beside the Mattamuskeet Lodge. Minutes later, a flashlight procession rings the water’s edge, and muffled voices become more distinguishable.

“We caught an eel,” a voice calls out with decided excitement. “There’s an eel in the trap we set last night.”

That’s good news to Roger Rulifson, East Carolina University professor of biology and director of the Field Station for Coastal Studies at the Lake Mattamuskeet National Wildlife Refuge. He’s hoping to begin research to help pinpoint — and control — a parasite that is taking a heavy toll on the once abundant eel fishery.

Mattamuskeet Lodge. Photo by Pam Smith.

But he’s put his own research interests on the back burner this weekend. He and ECU colleague, Steve Norton, have taken 16 fisheries and marine biology students to the famed Hyde County refuge for field training in fisheries techniques.

Here, they’ll put into practice textbook methods they’ve studied. They’ll work in teams to gather data on such things as water quality and fish distribution.

For many of these university seniors and grad students, this is their first hands-on experience with fishing gear. Understanding how nets and other equipment are used is essential for those planning careers in fisheries resource management, Rulifson explains.

First off, they learn that fisheries-related careers demand long hours of hard work.

Their “workday” begins at 6 a.m with the first of the six daily water samplings at several sites on the pond, lake and Pamlico Sound. They won’t complete the scheduled tasks until they have set, retrieved and reset gear six times, recorded each catch, shared and compared observations from the day, and organized data. Lights out could be midnight or later.

The Mattamuskeet experience will be the basis for required end-of-term scientific papers — the best of which will be submitted to U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) for annual collection records.

The 50,000-acre Lake Mattamuskeet Wildlife Refuge is managed by the USFWS. A 1994 agreement allows ECU to use the lodge as a field station for studying wetlands, watersheds, estuaries and sounds — and how they are affected by coastal growth and development.

The lodge and refuge have been the base of operation for long- and short-term research projects by scientists from ECU, North Carolina State University, Notre Dame University and Arizona State University. Their studies reflect the biodiversity of the refuge.

“With five national wildlife refuges and two state parks in the area, the field station at the lake is the perfect place for training students in a variety of academic disciplines. This area is bursting with potential,” Rulifson says.

Various attributes — the largest natural lake in North Carolina; acres of marsh, timber and crop lands; location on the Great Eastern Flyway of migratory waterfowl; proximity to barrier islands; and long history of civilization — add up to a rare combination of educational opportunities for students and faculty.

[Future use of the historic lodge may be in jeopardy because of structural problems. See page 11 for details.]

Immersed in Science

For his part, Rulifson focuses on fishery biology and fisheries management, while Norton looks at fish ecology and physiology.

“Researchers must know how to catch fish, and managers must know the biological basics,” Norton explains.

Their differences yield dividends for the students who find themselves on a weekend totally immersed in applied science at the refuge.

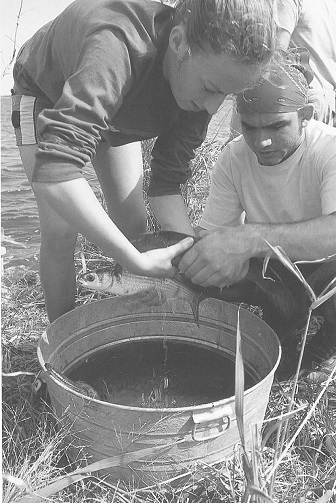

Students work quickly to move fish from nets to waiting tubs. The field study will provide a variety of species for lab work at East Carolina University.

Before breakfast, the students already have completed the first round of water quality data collection near the lodge.

Now, with gear packed into a van and pick-up truck, they head down the unpaved road that follows the canal seven miles from the lodge to the Pamlico Sound.

A petite brunette — nearly swallowed whole by waders —joins classmates walking a seine net into the near-shore waters of the sound at the mouth of the canal. Other students are dipping black water into coolers that will serve as holding tanks for the morning catch. Still another group is recording water quality data — location, time, tidal information, water depth, turbidity, pH, salinity, oxygen, sediments, conductivity, and water and air temperatures.

Later, they’ll match the data with the list of fish caught and the type of gear used at each site.

The students are having a difficult time pulling the net to shore in the shallow sound water. The tide is out, and the nets are weighted down with organic material — decaying grasses and shrubs that were deposited by hurricane-related flooding in 1999.

In spite of the difficulty, the seine has captured a fair sampling of fish — anchovies, kingfish, gobies, skillet fish, silver perch, croaker, red drum, flounder, a pinfish with a leech on its tail, and a mullet without a tail.

It’s a teach-as-you-go situation for Rulifson and Norton.

Rulifson points out mouth characteristics of two fish. “If the fish has an underbite, it’s a bottom feeder; if its mouth is turned up, it’s a surface feeder,” he explains.

The students continue to toss the fish into the waiting containers, calling out the litany of common names. In response, Norton chants the biological nomenclature. “Common names vary from place to place. In some places a skillet fish is any fish that can fit in a pan,” Norton says.

Back at the lodge workroom, the students work quickly to separate, bag and refrigerate portions of the catch. Rulifson and Norton will have plenty to share for lab work back at ECU — and the weekend is far from over.

“We prefer to use fresh-caught specimens for research,” Norton says. “Prepared and preserved ‘bought’ specimens may be tainted by chemicals.”

Testing Gear and Stamina

Over lunch, the students talk excitedly about their work. Purvi Mody, a senior majoring in ecology education, says, “You can’t get this kind of experience in a classroom. I want to learn the tools for fisheries management so I can bring the skills to developing countries after I graduate.”

She won’t be disappointed with the afternoon schedule meant to test gear, stamina and some preconceived notions.

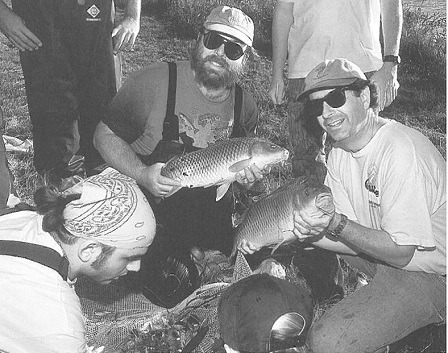

Steve Norton and students are pleased with the catch.

At the out-take canal side of the Point on Lake Mattamuskeet, students fight a steady wind and strong current to pull in an experimental gill net they had set earlier. The net has five sections, each with differently sized mesh openings from one-inch to five-inch stretched mesh. They will inventory the catch according to mesh size.

No matter what size the mesh, they discover it’s often difficult to extract the fish from gill nets. The gar are fierce fighters and weave themselves into mesh openings with their needle-shaped noses. Some can be removed only by snipping the net.

Gar, which run in both fresh and salt waters, top the inventory list for this collection time and site. One fish measures better than 86 cm. Bowfin are second in abundance.

Both are air breathers and can adapt to low oxygen levels in water because they surface to breathe, Norton explains. Their swim bladders serve as lungs to absorb and release oxygen. “It’s a primitive adaptation of fish,” he says. The swim bladder is for buoyancy, filling or releasing gas as fish change depth.

Handling a hoop net in shallow canal waters can be tricky.

Talk about adaptation. The salinity is zero, yet the catch includes ladyfish and blue crabs — both saltwater species. Moreover, the canals that lead from the lake to the sound are fitted with flap gates to keep brackish and saltwater — and salt-loving creatures — from entering the freshwater Jake environment.

“Obviously some critters get through at some stage of their lives and thrive in freshwater,” Rulifson says. As though to prove the point, a blue crab, measuring about eight inches from point-to-point, stubbornly clings to the net.

“No commercial crabbing is allowed at Lake Mattamuskeet, and recreational crabbers can’t use crab pots here,” be adds.

Water testing continues as a fyke net is set on the opposite side of the point, where the current is not as swift. Rulifson describes the fyke net as a hoop net with wings.

This method of fishing dates back to biblical times, Norton tells the students. It’s been modified according to geographic region and culture. “It’s definitely multicultural and multinational in origin. The material will vary according to what’s available. In the tropics, they might use reeds, in South East Asia, probably bamboo.”

Students walk a net through near-shore waters of the Pamlico Sound.

The catch is slim this time.

The students reset the gill net and move on to an inner canal to explore the confined, brackish canal water environment. The wind has died down. Rulifson and Norton expect some stratification of the water column, with freshwater at the surface.

The pH of the water tells something about the water source and the kinds of fish that can live there. Basically, they are standing in a peat bog.

Though not bountiful, the fyke yields some additions to the day’s inventory — a bluegill or bream, war mouth (another type of sunfish), and a three-inch threadfin shad.

Shadows are growing longer, but there still is work to be done. The group returns to the lodge. While one team sorts and stashes the catch, another moves to sites around the pond to conduct water quality testing.

On a flood control structure near the lodge, Jason Reuter, a graduate student in marine biology, is collecting water quality data. He did his undergraduate studies in sociology and ultimately plans to pursue a doctorate in coastal resource management. “I want to make the connection between marine biology and policy,” he says.

Reuter says the field study is helping him hone research methods. “Tonight, we’ll get together to chart all the data we have gathered today. We’ll put it on the board and look for anomalies. We’re using different kinds of water-sampling equipment to test the same water quality variables, and the numbers may be different. We’ll discuss why this happens, and determine what equipment and method may be the best for these purposes.”

The nightly wrap-up sessions ensure that all students will have the same data set for their end-of-term projects.

The weekend also is teaching students that field work often requires a bit of creative improvisation.

“Duct tape. Always carry duct tape,” Reuter advises. “To get a water sample from this point on the flood control structure, we taped a paper cup to the end of a pole to reach the water.”

Call it a Wrap

The kitchen crew is swinging into action to prepare a spaghetti supper for the tired and hungry group. But before dinner is served, a skeleton crew will make a run to the Point to pull the gill net.

A small number wait in the workroom, ready to process their catch. They informally assess the weekend activity and share thoughts about the kind of research they have been scoping out at the refuge.

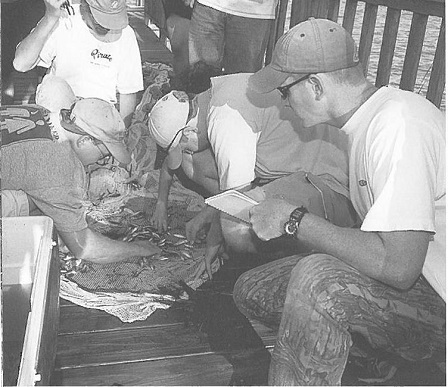

The task of sorting and recording each catch is time-consuming.

Charlton Godwin, a senior marine biology student, is interested in doing a fish control/water control study. He intends to study the biological and water quality effects of the recent retrofit of the flap gates used to keep saltwater and fish from passing into the freshwater lake. It won’t be the first study for him. He’s looked at the aging of Atlantic needlefish from the lake, reading rings in the otoliths, or fish earbones.

The outer door bursts open, and students explode into the room talking all at once about the catch of the day — a 46-cm largemouth bass. They returned the fish to the Jake to delight another angler on another day.

A grinning Rulifson affirms. “It was a trophy catch. Only wish I had him at the end of my fishing rod.”

By Sunday, students and faculty are calling the weekend a success. The gear has worked, over 40 different species of fish are recorded, and the data sets are complete.

“It has been a great weekend for the students and instructors. Every year we have different ‘war stories’ to tell. This year it will be the rain and wind, trophy bass, and giant gar,” Rulifson says.

“And what a great team-building exercise! These students have gone through four years of college, had each other in the same classes, and never knew their names. Now, they’ll have a lifetime of memories about these fellow students and activities from this one, short weekend.”

David Gloeckner, a graduate student, agrees. Now a fisheries port agent in Beaufort for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), he has served as a NOAA observer on an ocean-going vessel.

Gloeckner says the Mattamuskeet weekend successfully imitated life in the field. “We’ve been cold and sleep-deprived. Only thing missing — 20-foot seas.”

This article was published in the Spring 2001 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.