By CYNTHIA HENDERSON VEGA

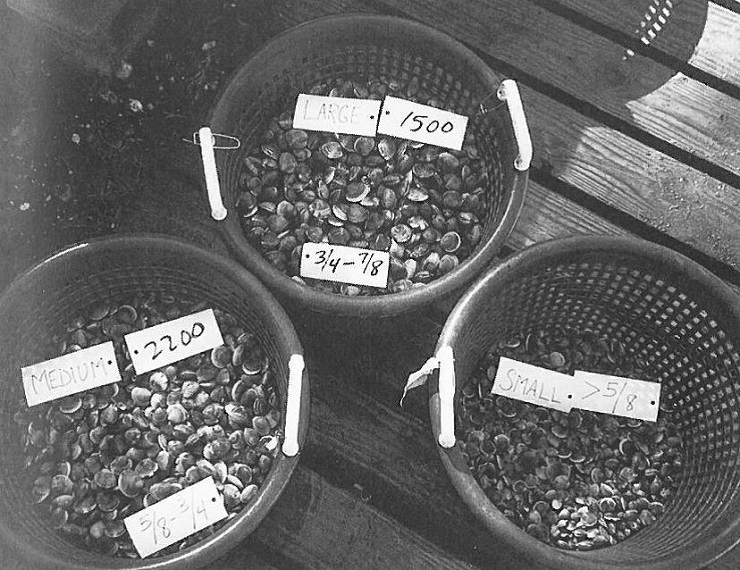

Young clams are graded after spending their first year in bags. Photo by Mark Hooper.

Want to know how to keep a clam as happy as, well, a clam? Mark Hooper’s got it in the bag.

With support from the Fishery Resource Grant program (FRG), Hooper is using bags to dramatically increase the survival of hard clams during the first critical year of grow-out. His findings could make other North Carolina clam mariculturists happy, too.

For their first year, tiny clams are taken from the protective environment of the nursery and planted in the bottom beds of open waters — where the wild things are.

The clam nursery at Hooper Family Seafood is a series of raceways on a dock on the Core Sound in Smyrna. A great blue heron lifts noiselessly from its hiding place near the clear water’s edge. It’s peaceful, but beneath the water’s surface … it’s a jungle in there.

Blue crabs, mud crabs, snapping shrimp and whelk are a few of the things that go chomp in the night — or any time, for that matter. Typically, Hooper says, clam farmers try to protect young clams by covering them with polypropylene mesh. Even this protective covering, however, cannot prevent the 50 percent mortality that is common the first year. The statistics are daunting for anyone considering clam mariculture as an alternative to harvesting from increasingly pressured wild stock.

In Florida, mariculturists found a way to beat the odds, decreasing mortality by raising clams in tented mesh bags. Now, according to Leslie Sturmer, Sea Grant shellfish aquaculture extension agent at the University of Florida, the bag method is the only way clams are raised and harvested there, bringing in around $12.7 million annually.

Sturmer says other states have tried to follow Florida’s example, but most have been unsuccessful. The farther northeast the state, she says, the less effective the bag system is. She speculates that Florida’s success may be because the warmer climate means a shorter grow-out period — 12 to 15 months. In North Carolina, grow-out periods are two years or more.

Hooper tested a variation of the Florida system with his FRG project. He, too, had problems. The clams grown in bags were significantly smaller after the first year than those grown in beds. But his success lay in the survival rates of clams raised in bags.

Hooper says “mortality is primarily a first-year problem.” That’s when clams shells are too thin to defend against the jaws and claws of the deep. Bags protect newly planted clams by forming four-by-four-foot tents around them supported by center stakes of 12-inch long PVC pipes. The bags are secured at the corners, with clams piled in the centers.

Clams don’t grow as large in this maricultural tent city — possibly because of a decreased flow of nutrient-carrying water to the bivalves or because of competition for food. In nature, clams feed by burrowing under the substrate. Siphons extend up, taking in plankton and microorganisms carried along by water currents.

It takes valuable growing time for sediment to accumulate in the bottoms of bags and simulate a natural environment. So clams grow more slowly, but, because they are protected from predators, more survive.

Hooper has found 13 mm to be an optimal planting size. That’s bigger than the diameter of a number-two pencil, smaller than a dime. Planted in bags at this size, his clams had an impressive 90 percent survival rate.

The Hooper variation combines the bag and bed methods, increasing survival with bags the first year, then planting in beds the second year to catch up in growth. The method has proved so successful, Hooper says he now uses it exclusively.

The bag/bed method has the additional benefit of allowing Hooper to grade the clams before planting them in beds. When clams are harvested with the bed method, those too small to be sold are replanted to keep growing.

Now when Hooper pulls his bags up after the first year, he separates them and plants similar sizes together. He saves final harvesting time by starting with beds where the largest clams were planted.

In a current FRG project, Hooper is investigating this grading system in order to improve shellfish crop management. It’s a matter of one good project leading to another.

Hooper wades into his clam beds staked off in the glistening sound. A gull laughs raucously as Hooper gently rakes up 175 clams to fill an order. It doesn’t take long. He picks up a perfect, nicely rounded specimen and proudly points out the smooth white edge that, he says, “indicates a good year’s growth.”

On the dock, a few small terrapins peek up from a watery containment. Hooper is interested in ways to prevent terrapin entrapment in crab pots. Another FRG project? Could be. As Hooper says, ”We’ve got a lot of ideas around here.”

This article was published in the Winter 2001 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.