Posted June 7, 2016

Editor’s Note: As the National Sea Grant College Program celebrates coastal tourism in June as part of its 50th anniversary, we are pleased to offer this guest post from our friends at the North Carolina Office of State Archaeology, Underwater Archaeology Branch.

“We are excited to see and share innovative and sustainable tourism plans from our partners along our coast,” notes Jack Thigpen, North Carolina Sea Grant extension director.

North Carolina has a rich and diverse maritime heritage, a cultural inheritance that is shared by all the state’s residents. From our extensive river system, to the broad estuaries and sounds, and out through numerous inlets to the open ocean, North Carolina has been shaped and developed by maritime commerce.

Historical records show that there are more than 4,900 shipwrecks within state waters. Almost 1,000 have been located and documented by archaeologists. These sites — what we like to call our state’s nonrenewable, submerged cultural resources — encompass every period of North Carolina’s history.

Condor’s starboard engine. Photo courtesy UAB |

Condor’s starboard paddlewheel. Photo courtesy UAB |

To protect these tangible and fragile legacies lying beneath the waves, North Carolina’s Office of State Archaeology’s Underwater Archaeology Branch, or UAB, seeks to create a sense of stewardship for our shared maritime heritage throughout the diving community. The key to achieving this goal is educating North Carolinians and potential visitors about this resource, training volunteers to work with maritime archaeologists, and opening shipwrecks for divers to “take pictures, leave bubbles.”

In July, the UAB will initiate a diving park, the first of what will eventually be developed into a heritage trail for divers, at the site of the Condor, not far from our office at Fort Fisher.

Our first step will be training local divers and dive professionals from the Wilmington area. We will ask these divers to help us update the site map of the Condor, one of the numerous blockade runners lost during the American Civil War.

We intend to use this new data to create a dive slate, which will enable other divers to visit the site and take a self-guided tour of this historic vessel. Eventually, the UAB plans to install a pair of mooring buoys, turning the Condor into North Carolina’s first “in-sea museum.”

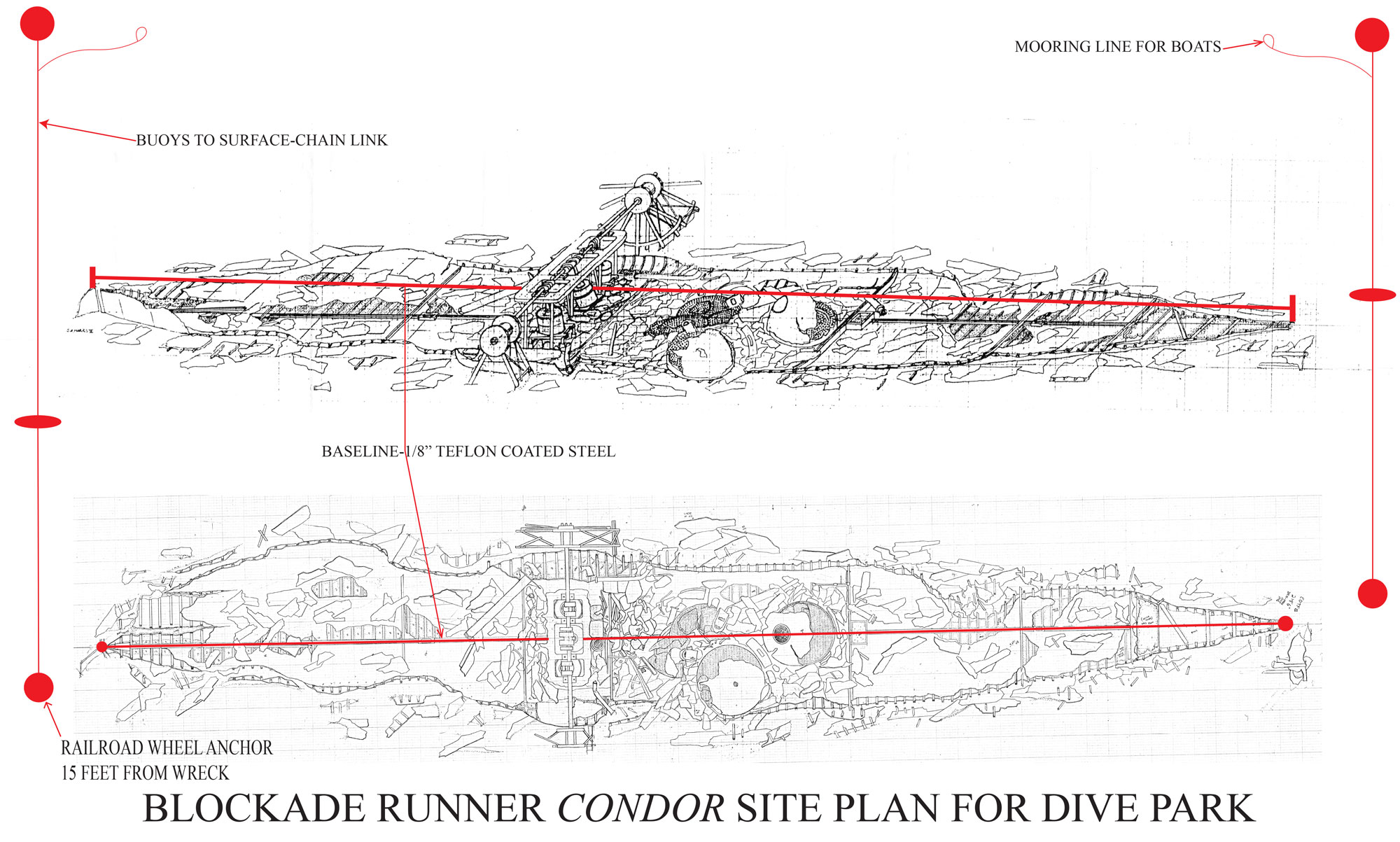

Views of the Condor from the top and side. The illustration also shows where proposed mooring lines will be added to encourage divers to visit. Image courtesy UAB

Florida pioneered this concept in 1991 and now has 12 heritage dive sites. This effort has enabled that state to protect these underwater resources.

Condor has a fascinating back story. It was one of five Falcon Class steamers, built on the Clyde River in Glasgow, Scotland, for the lucrative trade of blockade running.

Steaming through the cordon of Union naval vessels blockading the port of Wilmington, North Carolina, on her maiden voyage, Condor ran aground and was lost on the night of Oct. 1, 1864.

Rose O’Neal Greenhow was a Confederate spy who was on the Condor blockade runner. Courtesy Rose O’Neal Greenhow Papers/Special Collections Library, Duke University

On board that night was Rose O’Neal Greenhow, the famous Confederate spy, who was returning to the Confederacy after a trip to England to raise funds for the Southern cause. Fearing capture and possible execution by Union leaders, Greenhow insisted on being rowed ashore, despite the vehement protests of the captain and officers of Condor.

A volunteer small-boat crew finally attempted to get Greenhow ashore, but rough seas and breaking waves capsized the boat and she drowned. She is buried in Oakdale Cemetery in Wilmington. To this day, her gravesite often is bedecked with flowers and flags, left as homage to the “Wild Rose” of the Confederacy.

Condor rests in 25 feet of water, about 800 yards off the beach in front of the North Carolina Aquarium at Fort Fisher. She is one of the best-preserved blockade runners found anywhere in the world.

Her full lower hull, engines, paddle wheels and boilers all are still in place. The vessel is laid across the sea floor like a drawing of the high-tech, stealthy steamer she was when she sailed for Wilmington with her cargo and illustrious passenger more than 150 years ago.

Our goal is to make the Condor the first true heritage dive site in North Carolina, offering divers a glimpse into one of the most intriguing aspects of North Carolina’s maritime legacy.

John W. “Billy Ray” Morris is the director of North Carolina Office of State Archaeology’s Underwater Archaeology Branch. He has more than 28 years of field experience directing projects in the United States and abroad. Morris has worked on shipwrecks, including the Confederate raider CSS Alabama off the coast of France; a 16th century Spanish messenger vessel in Bermuda; and the Betsey, an 18th century British transport lost at Yorktown, Virginia, during the American Revolution.

Greg Stratton is the archaeological dive supervisor for UAB. He has served as a research diver on the Queen Anne’s Revenge Shipwreck Project for the past three years and served as director of operations for the 2015 field season. He has participated in a variety of maritime archaeological projects in the United States and overseas, including Sweden, Greece and Albania.

For more information about the Condor project, contact Morris at John.Morris@ncdcr.gov and Stratton at Greg.Stratton@ncdcr.gov.