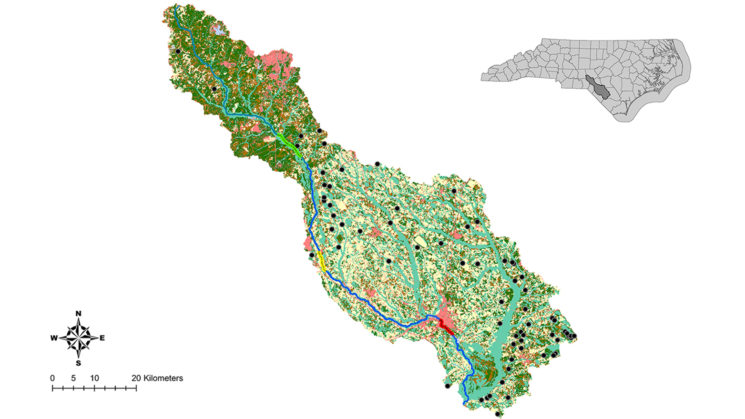

The Lumbee River Basin, southeastern North Carolina: forests (green), agriculture (yellow), urban areas (red), streams/rivers (blue).

BY JUSTINE NEVILLE

2018 North Carolina Sea Grant – WRRI Graduate Research Fellow

Throughout this post, I refer to the river as “Lumbee” in observance of the 2009 Lumbee Tribal Government Ordinance CLLO-2009-0625-01: “Reclamation of the Lumbee River’s Ancestral Name.” State and federal agencies have referred to the river as “Lumber” since 1809.

As the global population has exploded over the last century, nitrogen has become one of the most common water contaminants in the world. Nitrogen contamination originates mainly from human-related sources such as car emissions, fertilizers, livestock waste and urban runoff. For decades, scientists have observed nitrogen concentrations rising in water bodies around the world, but especially in developed nations. The over-abundance of nitrogen in natural waters leads to negative impacts on water quality, including harmful algal blooms and fish-kills, which have adverse effects on downstream economies and ecosystems.

Justine Neville: “No matter the season, I paddled my canoe through the forested Lumbee River reach to take water samples.”

Luckily, many aquatic and wetland ecosystems can remove some of this nitrogen before it becomes a nuisance to downstream environments. The plants and microorganisms of these ecosystems naturally remove nitrogen from rivers and streams, benefiting coastal fisheries and estuaries. However, these organisms can be sensitive to environmental disturbances. During large floods, for example, vegetation can be uprooted from wetlands and microbial mats can be scoured from stream beds. These and other disturbances could have major implications for nitrogen cycling.

In 2016, Hurricane Matthew brought immense and devastating flooding to the Lumbee River, located in southeastern North Carolina. As flood waters spread far beyond the existing floodplain, towns and farmland alike were submerged. Unknown amounts of debris and contaminants were transported downstream. Because flooding from Hurricane Matthew was so much larger than anything the Lumbee River had experienced in the observational record, or in the oral and written histories of local residents, the flood had unknown implications for the river’s nitrogen cycle. Together with my advisor, Ryan Emanuel of NC State University, I hypothesized that ecosystems responsible for removing nitrogen from surface waters may have been damaged or altered in ways that affected rates of nitrogen removal.

To test our hypothesis, we tracked changes in the river’s ability to remove nitrogen in one of its inorganic forms, nitrate. We measured nitrate concentrations in water samples collected along three reaches of the river for several months before and after Hurricane Matthew. We combined these measurements with other data from the river to compute nitrogen uptake rates for subsections of each reach. For two of the reaches, average rates of nitrogen uptake did not change appreciably following Hurricane Matthew. For the third reach, the average rate of nitrogen uptake decreased slightly following the flood.

Justine Neville

More interestingly, we found that variability in nitrogen uptake within each reach increased substantially following Hurricane Matthew. We believe these differences may stem from disturbances inflicted on wetland vegetation and microbial mats, which actively remove nitrogen from the stream. These communities were not completely scoured away by the storm, but flooding may have impacted them enough to create spots along the river that were especially effective (or ineffective) at removing nitrate. As time passed, variability in nitrogen uptake appeared to decrease within each reach. The changing behavior of nitrogen uptake following Hurricane Matthew raises interesting questions for future research.

Following major floods like those caused by Hurricane Matthew and, recently, Hurricane Florence, local and federal governments pay more attention to vulnerable communities living in floodplains or in other low-lying areas. This attention is appropriately aimed, since these communities are often inadequately equipped to recover from floods and adapt to changing climate. However, hurricane-related flooding can also impact unseen ecosystem processes responsible for mitigating nitrogen pollution in surface waters. It is therefore imperative that we understand how major floods can affect the processing of nitrogen and other contaminants.

This holds true especially in light of current projections that hurricanes such as Matthew and Florence will become more commonplace, bringing catastrophic floods with them. Once we understand extreme floods and their impacts more fully, we can gain a clearer picture of how ecological processes, including nitrogen removal from streams, behave in the months and years that follow. Will nitrogen processing return to pre-hurricane state or shift to an alternate state? Future research will help answer this and other questions related to water quality in an era of global change.

This post originally appeared with data graphs here.