Posted April 15, 2016

When the containership Benjamin Franklin visited the U.S. West Coast earlier this year, it drew attention during stops at the ports of Long Beach and Oakland in California, and in Seattle.

Longer than 3.6 football fields, the Benjamin Franklin is the largest containership to ever call on the United States. It can carry up to 18,000 containers, known as 20-foot equivalent units, or TEUs.

These containers transport everything from the clothes you’re wearing, to the banana you had for breakfast this morning, and the computer that you are using now. A single 20-foot container can hold 48,000 bananas, and if that were the Benjamin Franklin’s sole cargo, it could carry up to 864 million bananas!

The number of people it takes to operate this behemoth across the seas and into our ports to deliver two bananas for every person in the country? Only 26.

As the 2016 Sea Grant Knauss Fellow with the U.S. Committee on the Marine Transportation System, or CMTS, I’ve had the amazing opportunity to meet some of the people who make the nation’s marine transportation system run smoothly and efficiently.

The CMTS is a partnership of federal departments and agencies that have oversight of or interest in the marine transportation system — including vessels, navigable waterways, ports and landside connections (such as railroads and trucks) that help move people and goods to, from and on the water.

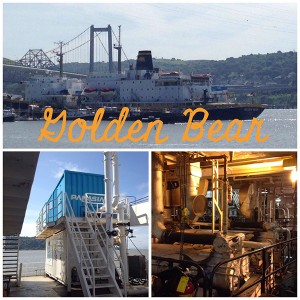

All the vessels along the California Maritime Academy waterfront are learning tools for students, from barges to tugboats. The campus is pictured in the background.

This spring, at the California Maritime Academy, or Cal Maritime, I met many of the individuals who work, or are being trained to work, on our nation’s vessels, tugboats and barges that operate on more than 25,000 miles of U.S. waterways.

I was at the academy in Vallejo, California, for a conference recognizing and supporting women in the maritime industry. Over three days, I met more than 100 cadets from the seven U.S. maritime academies. Cal Maritime is one of six state maritime academies, along with one federal merchant marine academy, that train students for a career on the water.

Despite a long history of seafaring, women were barred from attending the maritime academies until 1974. In 2014, of the 1,047 undergraduate students enrolled at Cal Maritime, just 14 percent were female. At the other state maritime academies, 8 to 13 percent of the students are female, while almost 20 percent of the student body at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy is women.

During a tour of the Golden Bear, Cal Maritime’s training vessel, I visited the ballast water-testing facility (bottom left) and the engine room (bottom right).

A unique feature of attending a maritime academy versus a more traditional college or university is the specialized hands-on learning aboard training ships. The Golden Bear is Cal Maritime’s 400-foot training vessel for its students. This floating classroom also serves as a dormitory for freshman students while anchored at the campus.

During the summer, students can participate in two extended training cruises aboard the Golden Bear. She sails from Cal Maritime through the Panama Canal, headed for the East Coast and international destinations. A Cal Maritime student gave me a tour of the vessel.

My tour started on the bridge, the realm of the “deckies,” or students who are training to be mates and captains. From there, I could see the control and communications capabilities for the whole vessel. Moving downwards through the nine decks (this is not your average boat), I visited the galley, sleeping quarters and classrooms. Eventually, I made it to the belly of the vessel, the engine rooms and realm of the tour guide, who is studying to be a ship’s engineer. A ship engineer is responsible for keeping the engines — and almost everything else! — up and operating correctly while the vessel is at sea.

The last stop on my tour of the Golden Bear was the saltwater ballast testing facility. Ballast water is water taken on by the ship to increase the vessel’s stability as its cargo load changes, but can be a pathway for invasive species. It is estimated that more than 10,000 marine species are transported around the world every day through ballast water. Since the Golden Bear consistently conducts cruises, it serves as a platform to test and compare ballast water-purification technologies.

Speakers at the Women on the Water conference included, from left to right, Capt. Debbie Dempsey, who graduated in the first class of female cadets from the Maine Maritime Academy; Capt. Lynn Korwatch, who was in the first class of female cadets at the Cal Maritime Academy; Capt. Nancy Wagner, who was in the first class of female cadets at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy; and Capt. Kate McCue, the first American female captain of a major cruise ship.

“Transportation is not a cost, it brings value,” noted Capt. Lynn Korwatch, one of the first women to graduate from Cal Maritime and now the executive director of the Marine Exchange of the San Francisco Bay Region.

In North Carolina, the ports of Wilmington and Morehead City are two such examples of an industry that adds value to the surrounding communities. A study from NC State University’s Institute for Transportation Research and Education identified that North Carolina ports alone support more than 76,000 jobs in the state. These jobs — within the ports and in the service industries that support them — contribute more than $14 billion to the state’s economy.

While I came into this fellowship understanding the important role of maritime transportation in sustaining global commerce and connectivity, I did not recognize the complexity of the maritime industry. I perceived our containerships and tugboats in an autonomous, “Lightning McQueen” or “Thomas the Tank Engine” manner. The “Mr. Conductors” behind those modes of transportation were invisible to me.

When water-based transportation is the most cost-effective method to transport goods, it’s easy to just eat your breakfast and not notice the industry behind it. This fellowship has opened my eyes to the people who enable our maritime transportation industry to succeed — from the women and men in the U.S. Coast Guard who protect and monitor our vessels to the maritime academy graduates who pilot the ships safely to port.

Tomorrow morning as you eat your breakfast, think of the women and men who guided the vessel and worked in the engine room to get that banana into your hands.

Supriti Jaya Ghosh is the policy advisor to the director at the U.S. Committee on the Marine Transportation System. Ghosh’s areas of expertise include maritime energy and air emissions, environmental stewardship, and the National Ocean Policy. She holds a master’s degree in environmental management from Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment.

In this room simulating the bridge of a vessel, Cal Maritime cadets participate in a training drill where a tanker has lost power. As they navigate the vessel, the projections in the room rotate accordingly around them.