Photos courtesy N.C. Coastal Reserve and National Estuarine Research Reserve

Posted July 20, 2016

After carefully weaving between sandy shoals lining the waterways of Back Sound, Danielle Keller drops anchor and starts gathering her research equipment. As the tide falls, oysters spit and least terns dive-bomb the shore as a warning to not come any closer to their nesting areas.

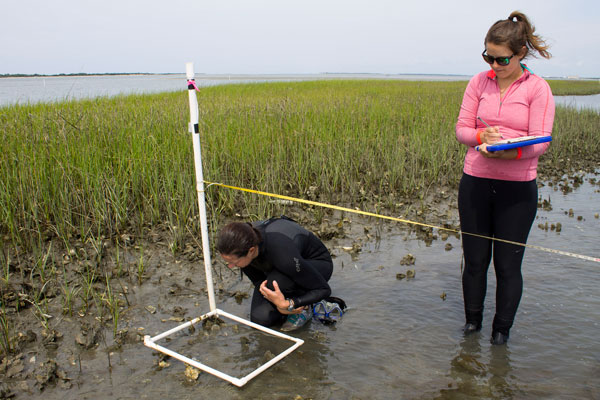

Coastal research fellow Danielle Keller (right) and Brandon Puckett (left), N.C. Coastal Reserve and National Estuarine Research Reserve research coordinator, conduct seagrass surveys in Middle Marsh.

Keller, a doctoral candidate in Joel Fodrie’s lab at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Institute of Marine Sciences, studies the seagrass communities covering the seafloor of Middle Marsh, part of the Rachel Carson Reserve. Today, she isn’t distracted by the activity above or below the water.

But it’s not always this peaceful. Once, a shark swam at her while she had her head submerged in seagrass. That encounter had her almost leaping into colleague Mariah Livernois’ arms for safety.

“It was just a 3-foot bonnethead shark,” Keller recalls, admitting that visions of a 10-foot bull or tiger shark charging at her. “A huge wave of relief washed over me while my heart was still beating out of my chest. After a few minutes, I went back to surveying the seagrass, with Mariah as my bodyguard.”

Keller is evaluating how different seagrasses serve as nursery and refuge areas for fish species such as gag grouper and gulf flounder. She conducts this research as part of her North Carolina Sea Grant and N.C. Coastal Reserve and National Estuarine Research Reserve Coastal Research Fellowship. “I’m interested in understanding how fish communities respond to seasonal changes in seagrass cover,” Keller says.

“Seagrass is a critical habitat for juvenile grouper and flounder. Danielle’s work will help researchers and resource managers understand how a potential shift of habitat from eelgrass to shoalgrass could affect these important fish species,” says John Fear, Sea Grant deputy director.

According to the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries, between 134,000 and 200,000 acres of submerged aquatic vegetation exist in North Carolina’s estuaries. In addition to providing shelter for economically important fish, crabs and invertebrates, seagrasses buffer wave energy, stabilize sediment and filter pollutants.

“Seagrass meadows are especially susceptible to temperature increases, which have an effect on biochemical reactions, important to their growth, production and overall functioning,” Keller explains. “The effects of increasing water temperature are enhanced in the summer.”

Middle Marsh is home to three types of seagrasses. Eelgrass (Zostera marina) is the predominant species, followed by shoalgrass (Halodule wrightii) and widgeongrass (Ruppia maritima).

When undergoing sexual reproduction, eelgrass, Zostera marina, produces large quantities of seeds.

The hardiest of the three species, eelgrass entices juvenile fish needing refuge from predators with its thick, tall leaves. Shoalgrass, on the other hand, has thinner and shorter leaves but can tolerate warmer water temperatures and grow at shallower depths. For these reasons, each year, shoalgrass persists as the summer heat kicks in and the eelgrass dies off.

Keller seeks to answer several questions. “Can shoalgrass serve as redundant habitat for fishes and replace the void left behind by eelgrass, or do fish simply move on to different habitats following the eelgrass die-off?” she asks.

Her first step is to figure out what seagrasses grow at her research sites. Throughout the summer, she will conduct surveys to identify the presence and abundance of shoalgrass and eelgrass. In addition to the surveys, she will collect fish to understand how they respond to changes in seagrass cover.

Danielle Keller, left, is identifying what seagrasses grow at her study sites, aided by Mariah Livernois, right.

In addition, she will track the movement of juvenile gag grouper and gulf flounder using acoustic tags. This data will show movement patterns within different habitat types throughout the estuary. By tracking their movement, Keller can see where the tagged fish spend their time as shoalgrass replaces the dying eelgrass.

“Juvenile gag grouper, gulf flounder and so many other species use seagrasses as their nursery habitat. Without it, they would most likely not make it to adulthood for reproduction and continuation of their population,” Keller explains.

Find out more about the Coastal Reserve Fellowship here. And check the North Carolina Sea Grant website for the announcement seeking 2017 fellows later this year.

Emily Woodward is the public relations coordinator with the University of Georgia Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant. She is the former communications specialist with the North Carolina Coastal Reserve and National Estuarine Research Reserve.