Above: Marsh pink are native to dunes, maritime grasslands, and brackish and salt marshes. Photo by Paul E. Hosier.

Seacoast Plants of the Carolinas: A New Guide for Plant Identification and Use in the Coastal Landscape is now available in bookstores. The Summer 2018 issue of Coastwatch will offer an extensive Q&A with author Paul E. Hosier, as well as several excerpts from his book.

In addition to those excerpts, the snippets below also draw from the book’s first chapter: “Environmental Setting for the Coastal Carolinas.”

Geology and Geomorphology

The northernmost barrier islands, including Hatteras and Ocracoke islands in North Carolina, are geologically young, having reached their current dimensions and character less than 5,000 years ago. The South Carolina Sea Islands, best expressed from Bull Island to Hilton Head Island, are composed of both old and new ocean-derived sediments. The central core of these coastal islands is more than 25,000 years old, while a narrow ribbon of sand — usually comprising the ocean shoreline and adjacent dunes — is similar in age to the North Carolina barrier islands.

The region features four major capes: Hatteras, Lookout, and Fear in North Carolina and Romain in South Carolina. Scientists believe that Pleistocene Epoch sediments reworked by ocean waves and tides created these cape features. Cape Hatteras extends well into the Atlantic Ocean, and standing there, one immediately senses that this point of land is a tempting target for Atlantic hurricanes. In contrast to the North Carolina capes, Cape Romain today is composed of several dissembled islands that have evolved into a more or less diffuse cape feature. These complex cape features are typically home to a diverse suite of plants.

Courtesy of UNC Press

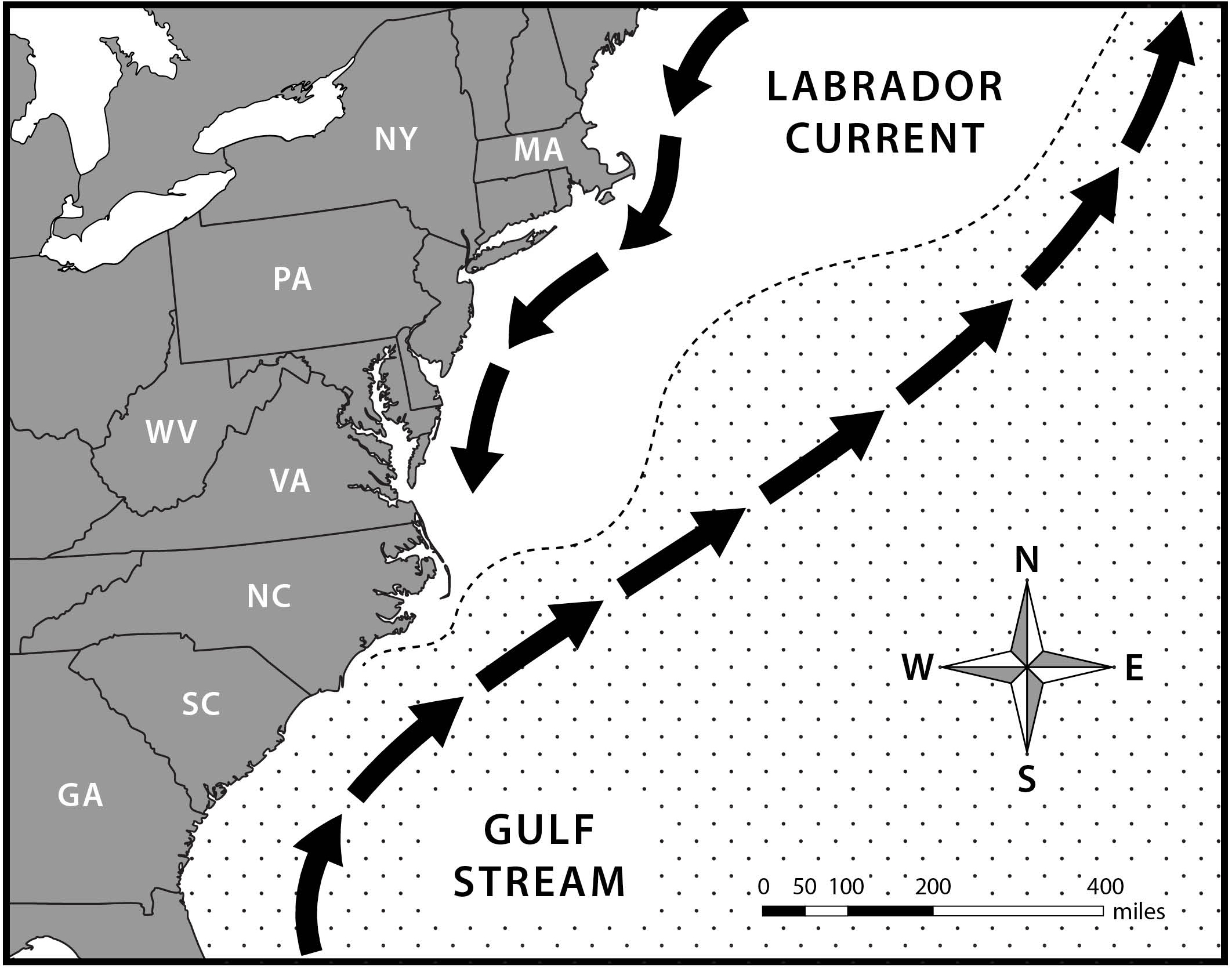

Ocean Currents

Two major ocean currents affect the coastal region of the Carolinas. The Labrador Current flows from its cold-water origin in the Hudson and Davis straits and the Grand Banks of the northwestern Atlantic Ocean south to North Carolina. The warm Gulf Stream flows northward from the coast of Florida, where it arises in the warm waters of the Florida Straits. This surface current generally follows the Carolinas coastline as it moves northward, turning eastward as it passes Cape Hatteras on its path toward the northeastern Atlantic Ocean. Eventually the Gulf Stream provides the British Isles with a warmer climate than its far northern latitude deserves. These two currents influence the distribution of plants along the Carolinas coast by bringing species with more northern affinities southward and plants with southern affinities farther north than expected.

Extremes of climate, weather, natural processes and events such as storms affect the health, survival and sometimes the distribution of plants and plant communities. The Carolinas coastal environment is agreeable in many ways, but it is not constant. Because individual plants are confined to one site for their entire lifetime, they have evolved wide tolerances for environmental conditions and developed unique adaptations to disruptive events. These conditions include extremes of water availability (flooding and drought), extremes of temperature, wind and fire. Certainly coastal storms present some of these factors all at once.

A sea rocket plant on a beach front dune in Fort Fisher, N.C. Photo by Gary Allen

Learn More About Seacoast Plants

Watch North Carolina Sea Grant social media for events with the author, and keep an eye out for the Summer 2018 issue of Coastwatch. In the meantime, check with your local bookstore and coastal gift shops for the book, or order online from UNC Press.

Also, members of the media or educators considering the book for a class can also contact UNC Press for a review copy.

North Carolina Sea Grant also will be working with partners, including those involved in the Coastal Landscapes Initiative, for special projects that include the book. Contact Katie Mosher at kmosher@ncsu.edu.

All book excerpts are shared with permission of UNC Press and NC State University.