BY OLIVIA CARETTI

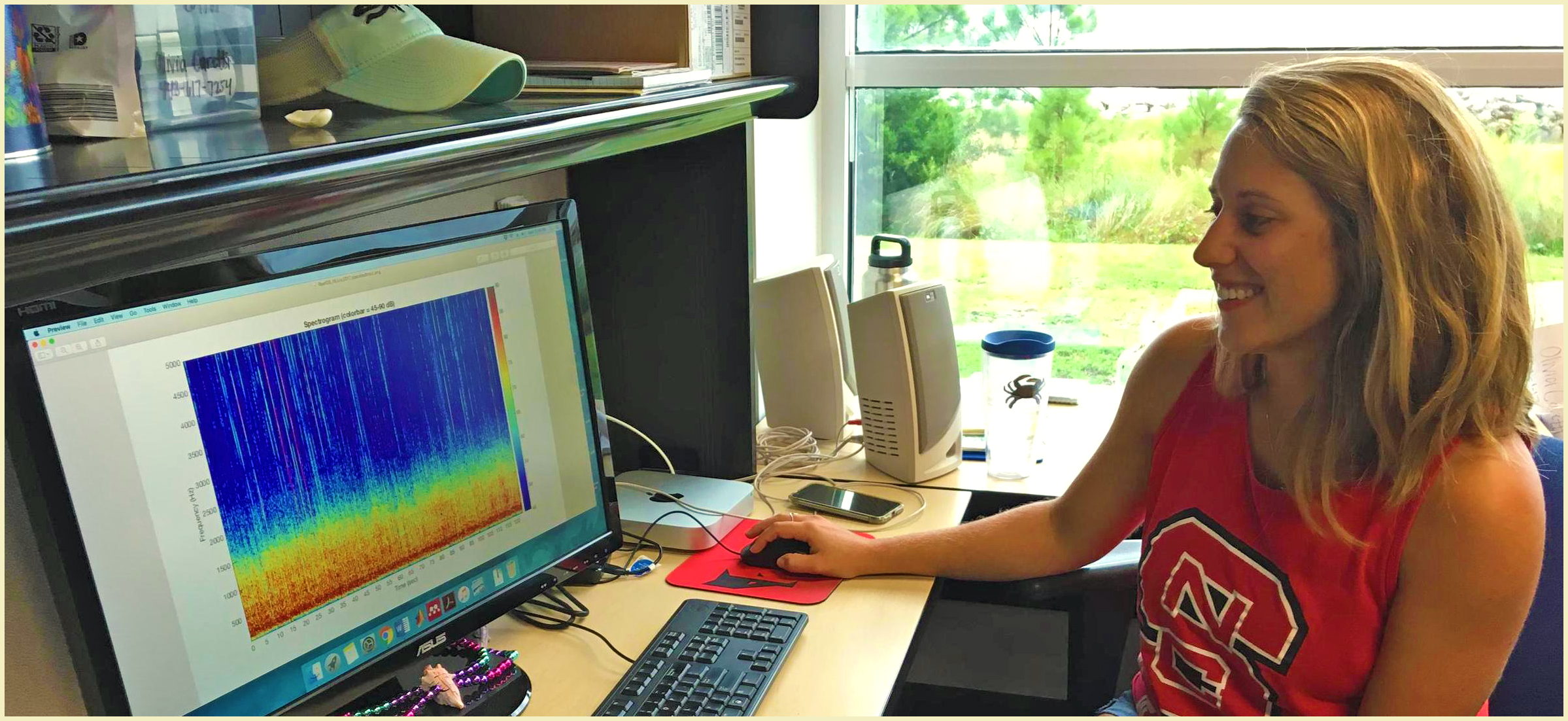

Olivia Caretti (above), an NSF Graduate Research Fellow in the Marine Ecology and Conservation Lab at NC State, serves on Dave Eggleston’s research team. North Carolina Sea Grant’s core research funding supports Eggleston’s “Evaluating Cultch Oyster Reefs as Essential Fish Habitat” project.

– Bernie Krause, soundscape ecologist and founder of Wild Sanctuary

We often think of the underwater environment as a quiet and still place. However, most of the ocean is full of noises from biological, geologic and human activity. Like humans, underwater animals use sound to communicate, navigate and search for food — and the underwater environment is full of signals associated with these behaviors. What can we learn by eavesdropping on these underwater conversations?

For my research, I am tapping into this natural set of behaviors to learn about how fish and invertebrates interact with their habitat — specifically how they use restored oyster reefs. Passively listening to animals in their natural environment provides a nondestructive and unique ability to monitor this, especially in estuarine systems where water is murky and where animals are constantly on the move and difficult to sample.

Our team at NC State collected two years of acoustic recordings on restored oyster reefs in Pamlico Sound. We coupled our recordings with habitat surveys to understand how fish responded to changes in their oyster reef habitat.

From our acoustic data, we can determine what species are present on restored oyster reefs, when they are present, and how they are using their habitat. For example, oyster toadfish make two different types of calls depending on their behavior: males make the “boatwhistle” call (listen here) only during spawning season, while the “grunt” call is used for day-to-day communication.

Moreover, acoustics have allowed us to identify spawning information for several important estuarine fish species. We have identified the exact date when such species as oyster toadfish, speckled trout, silver perch, and red drum begin spawning on restored oyster reefs in Pamlico Sound. We also can see how fish calling activity changes in response to local weather patterns. With a longer dataset, we even could look at how spawning activity for certain species may shift in response to climate change.

We also have seen the soundscape of restored oyster reefs change over time. Sounds from reef-dwelling species — such as oyster toadfish, red and black drum, snapping shrimp, and crabs — have become more common as reefs developed after construction. We even can see how different species make up the community on reefs built differently — in different locations, different areas, and with different materials. All this information can be extremely useful for informing goals and designs of oyster restoration projects.

Longer term acoustic monitoring could provide information on the recovery of habitats from large disturbances, such as hurricanes or “fresh-hit” events from intense inland flooding. Acoustic monitoring could show how quickly fish returned to reefs following a major storm. Essentially, changes in a habitat’s sound composition could indicate changes in habitat health and suggest its resilience.

Estuaries are dynamic habitats, and short-term changes in the environment can be difficult to track with traditional, intermittent sampling methods. Acoustics can track these short-term changes, as well as longer-term shifts, extremely well by providing an almost continuous record of information.

Just by listening, we can learn valuable information about the fish living beneath the sea, and this information can be crucial for conservation and restoration decisions. Listening to fish can uncover an entirely new perspective of our watery world.

Listen to the toadfish boatwhistle call

Read Olivia Caretti’s “What Can Researchers Learn by Eavesdropping on Fish?”

Listen to Olivia Caretti’s interview with WUNC radio

Read more about North Carolina Sea Grant’s core research funding

photo credit: Olivia Caretti