As the heart of the 2019 hurricane season approaches, you can access critical information through North Carolina Sea Grant’s portal to resources for hurricane and disaster preparation and recovery. We’re also pleased to offer here the first entry in the North Carolina Climate Office’s Stormy Summer series, which looks back at memorable hurricanes.

by Corey Davis

More than 100 years ago, two hurricanes 20 years apart tore up the North Carolina coast with little warning and a devastating impact along the Outer Banks.

That lack of advanced notice is unusual for modern-day storms, but the late 1800s were very different in many ways, including weather monitoring and prediction. Some of the only reports from storms at sea came from ships unlucky enough to be caught in their paths.

Until wireless telegraph communication using radio waves was possible in the early 1900s, those ship reports were not received on land until days or weeks after a storm passed by — often too late to help with forecasting.

Instead, many storms weren’t detected by the ground-based observing network until they reached land, and even those sparse reports often painted a limited picture of exactly where and how strong a storm actually was. That created some surprises when they arrived at our coast.

So why study storms from more than a century ago? In the cases of the 1879 Great Beaufort Hurricane and Hurricane San Ciriaco in 1899, they each hit the state with a strength rarely seen before or since, and while the stories from them are largely all that remains, those terrifying tales still leave us marveling at their intensity and wondering how bad their damage might be if they hit the state today.

The 1870s was a busy decade for hurricanes in North Carolina. Eleven storms in a nine-year period hit or passed near the state, with impacts including high winds, heavy rains, and flooding along the coastal rivers and sounds.

Mother Nature saved the worst, most severe storm of that decade in North Carolina for last. In August 1879, a tropical storm emerged from the void of the central Atlantic before grazing north of Puerto Rico, Hispaniola and the Bahamas.

Typical of the era, reports were limited from those areas, and were “not sufficient to justify the charting of its center”, according to the August 1879 Monthly Weather Review, issued by the General Weather Service under the then-War Department of the US. In other words, it wasn’t exactly clear where the eye was located or how intense the storm was.

As it approached the east coast of Florida, wind and pressure observations indicated the storm remained offshore, and over the warm waters of the Gulf Stream, it was gaining strength.

It was also a fast mover, covering the 500 miles from the northern Bahamas to Cape Lookout in just 24 hours. That gave little time for preparations as word spread and “Cautionary Signals” were raised along the mid-Atlantic coast.

As it arrived at the North Carolina coast, conditions deteriorated rapidly. At 5 am on August 18, winds at Cape Lookout were reported at 80 mph. Within the next two hours as the eye neared the Crystal Coast, gusts increased to 138 mph before the “anemometer cups were blown away,” reports say.

That was a common symptom of this storm, which became a sensor destroyer. Just before the eye’s arrival, winds of 80 mph were reported at Fort Macon, “and then the electrical connections failed.” Farther up the Outer Banks at Portsmouth, winds reached 97 mph before “the recording apparatus became temporarily disabled.” Cape Hatteras recorded winds of 74 mph before the anemometer “cups were blown away.”

Along with the high winds, the hurricane brought a then-unprecedented storm surge “over ground never remembered to have been overflowed before.” The Weather Service also reported that “the rain fell in torrents” totaling 4.29 inches at Cape Lookout, where “a fearful sea swept away the stable and outbuildings.”

The worst of the damage came along the eye’s path in the vicinity of Beaufort and Morehead City. Homes, businesses, railroad tracks, and at least two hotels were destroyed.

One of those, the Atlantic Hotel, was a popular tourist destination and even North Carolina governor Thomas Jarvis was visiting when the storm hit. An alarm was sounded at 3 am — just four hours before the eye arrived — but the brunt of the storm spared few.

“The Beaufort waterfront was demolished and under eight feet of water,” recalled Beaufort historian Mary Warshaw.

The governor and his wife made it out of the hotel, escaping without their personal belongings. Others weren’t as lucky.

In North Carolina and Virginia, 46 deaths were blamed on the storm. Among them was Henry Congleton, who first sounded the alarm at the Atlantic Hotel but drowned while rescuing vacationers stranded on the top of the building.

With an estimated 40 of those deaths in North Carolina, that puts the Great Beaufort Hurricane fifth among our state’s deadliest hurricanes, behind only Florence (45 deaths), Floyd (52), a hurricane in September 1883 (53), and the July 1916 storm in the Mountains, which was responsible for approximately 80 fatalities.

Hurricane San Ciriaco, 1899

Hurricane San Ciriaco, 1899In a curious coincidence of history repeating itself, 20 years to the day after the Great Beaufort Hurricane struck North Carolina, another hurricane was bearing down on our coast.

By the time the August 1899 storm arrived in North Carolina, it had already lived a full lifetime by Atlantic hurricane standards. Ten days before reaching our coast, the storm devastated Puerto Rico with a direct hit at Category-4 strength. That landfall came on August 8 — the date of the Catholic festival of Saint Cyriacus, known in Spanish as San Ciriaco, hence this storm’s common nickname.

In weather reports at the time, it was also called the West Indian hurricane. As it crossed the Bahamas, “all shipping bound for the South Atlantic were informed of the danger of sailing for that region,” notes the summary of the storm by E. B. Garriott with the US Weather Bureau, which was founded in 1890.

While the lead time for this storm may have been better than for its predecessor, limited observational availability still had its drawbacks.

Reports from the time indicated forecasters believed the center of the storm was tracking directly up the coast of Florida, Georgia and South Carolina, all while losing strength. Headlines suggested it was “dwindling away” and only a mild tropical storm based on the reported 45-mph winds in Savannah.

You can imagine their surprise, then, when the storm made landfall late on August 17 along the Outer Banks packing winds of more than 100 mph.

It wasn’t a case of rapid re-strengthening. Instead, later reanalyses beginning in 1900 as new ship reports were examined found that the storm remained more than a hundred miles offshore and was curving away from the east coast before high pressure to the east steered it back toward North Carolina.

Later efforts in the 1990s, including the National Hurricane Center’s HURDAT project that determined best-track and intensity estimates for historical storms and a separate reconstruction led by Jose Fernández-Partagás, concluded that the storm likely remained at Category-3 strength from the time it departed Puerto Rico through its eventual landfall near the north end of Ocracoke Island.

As the storm roared onshore on the evening of August 17, Cape Hatteras was in the right-front quadrant, where the estimated 121-mph winds plus the storm’s forward speed combined to produce the worst damage in the state.

At the Weather Bureau in Hatteras Village, observer S. L. Dosher noted sustained winds of 93 mph and gusts of 120 to 140 mph before the anemometer was blown away. By his account, “This hurricane was the most severe in the history of Hatteras. The scene on the 17th was wild and terrific.”

Fueled by the storm surge and more than 10 inches of rain that fell during the storm, flood waters covered Hatteras Island at depths ranging from 4 to 10 feet. Most houses were damaged, bridges were destroyed and roads were blocked by wreckage including downed telegraph and telephone lines.

Like the 1879 storm, Hurricane San Ciriaco had a deadly toll in North Carolina. Between 20 and 25 fatalities were attributed to the storm in the state, including 14 fishermen whose campsite was flooded and whose boats capsized while returning to the mainland.

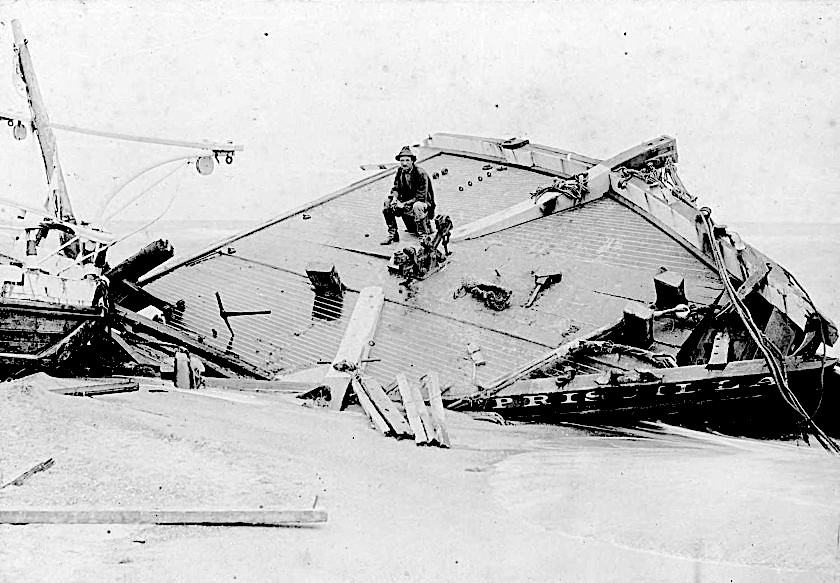

Rasmus Midgett sits on the wrecked remains of the Priscilla, courtesy of the H. H. Brimley Collection.

The hurricane also wrecked ships off the coast in the legendary Graveyard of the Atlantic. Among them was the Priscilla, from which emerged a tale of heroism among the tragedy.

The rough seas broke the ship in two and washed several crew members away. When the ship ran aground, Rasmus Midgett, on patrol for the US Live Saving Service, ran to it and rescued 10 remaining crewmen, carrying the final three exhausted men back to shore.

For his bravery amid the storm, Midgett received the Gold Lifesaving Medal from the Secretary of the Treasury.

As for the hurricane, its trip through North Carolina lasted just 12 hours, but it still had a long way to go in its journey across the Atlantic and back. The storm continued northeastward and became extratropical, but it redeveloped into a tropical storm a few days later and meandered over open ocean for nearly eight additional days.

In total, it was recognized as a tropical storm or hurricane for almost 28 days within a one-month period, making it the longest-lived Atlantic storm on record. But among that long life, its short stay in North Carolina makes it one of our state’s most notable hurricanes.

Both the Great Beaufort Hurricane and Hurricane San Ciriaco are officially listed as Category-3 storms at their landfalls in North Carolina, with sustained winds of 115 and 121 mph, respectively. But rumors within historical reports and the meteorological community have speculated for years that each storm could have been even stronger.

Those are based on the presence — or absence — of weather observations from the time. In both storms, anemometers were blown away, apparently before the strongest winds arrived.

So could these storms have been North Carolina’s earliest-known landfalling Category-4 hurricanes, predating Hazel by a half-century, or even our first Category-5 hurricane and an Atlantic record-setter?

Not so fast — literally. Other evidence from these storms helps refute those ideas.

During the Great Beaufort Hurricane, wind gusts at Cape Lookout were estimated at 165 mph on the back side of the storm, an hour after the anemometer cups were destroyed.

Although sustained winds that strong would rate as a Category-5 on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, remember that these were gusts — instantaneous spikes in the wind speed. Sustained 1-minute average wind speeds tend to be a bit lower.

For example, when the 138-mph gusts were reported at Cape Lookout, the sustained winds were 105 mph. Applying that same ratio to the estimated 165-mph gusts yields a sustained wind speed of 126 mph — slightly stronger than the estimated 115-mph sustained winds from the reanalysis data, but still a Category-3 on the Saffir-Simpson scale.

If anything, the barometric pressures measured along the North Carolina and Virginia coastline suggest it could have been a weaker storm than that. Cape Lookout (988 millibars), Norfolk (986 millibars) and Cape Henry, VA (984 millibars) all reported higher pressures than even Category-1 Irene (952 millibars) and Florence (958 millibars) when they made landfall.

Fernández-Partagás suggested that the minimum pressure in the eye should have been “significantly lower” than those readings — likely below 965 millibars. Although pressure isn’t directly tied to Saffir-Simpson Scale strength, it’s still a good proxy for hurricane intensity, and the readings from August 18, 1879, also help put a cap on that storm’s theoretical strength.

During Hurricane San Ciriaco, the barometric pressure from Hatteras was reported as near 26 inches of mercury, which translates to 880 millibars. If true, that would make this the most intense landfalling Atlantic hurricane on record, surpassing the 1935 Labor Day hurricane that hit the Florida keys with a minimum pressure of 892 millibars.

However, that reading is an obvious outlier compared to anything else observed by either weather stations or ships when the storm was along the North Carolina coast.

By comparison, Dosher, the official Weather Bureau observer, reported a minimum pressure of 28.62 inches of mercury, or 969 millibars, and the Washington Gazette reported that at Ocracoke, the lowest pressure during the storm was 28.3 inches of mercury, or 958 millibars.

The documents noting that potentially record-setting pressure seem to have disappeared like most vestiges of this century-old storm, but Fernández-Partagás noted that “the pressure reading near 26 inches seems to be the product of speculation.

“The facts that Hatteras experienced a minimum pressure of 28.62 inches and a lull in the evening of August [17] do not support such an extremely low pressure.”

While both storms washed away or blew away evidence that could reveal their true strength, the data we do have suggests that their current Category-3 designations aren’t too far off from reality.

Of course, that still makes them incredibly powerful hurricanes, and among only three known landfalling hurricanes of that strength in North Carolina, the other being Fran in 1996.

Considering the damage done both at the coast and inland by Fran, as well as the development and population growth over the past 120 years, it’s a bit frightening to think about what a present-day Great Beaufort Hurricane or San Ciriaco storm could do in North Carolina.

Even several generations later, another sensor-destroying, island-flooding, and ship-wrecking Category-3 hurricane would certainly put our coastal residents, landscape, and infrastructure to the test.

Adapted from this blog post from the North Carolina Climate Office, which also includes sources/citations.

Access North Carolina Sea Grant’s resources for hurricane and disaster preparation and recovery.

##