By Shannon Pelkey

Using a drone researchers are able to collect high resolution imagery of their living shoreline study sites. The imagery captures an oyster bag sill living shoreline that aids in protecting the fringing salt marsh from wave energy. As the image shows, the interface between water and land is preserved because of the way living shorelines are designed.

North Carolina’s estuaries are home to vast, lush salt marshes, mounds of oyster reefs, and flowing seagrass beds. These beautiful habitats provide a wealth of ecosystem services, including shoreline protection, sediment and nutrient filtration, habitat for our fisheries, and carbon sequestration, yet they are increasingly under threat.

Hazards that impact estuaries range from wave energy from boat wakes to severe storms, from unsustainable development to rising water levels and temperatures. To protect our homes and communities from coastal hazards, coastal managers use a range of solutions where the land meets the water, including hard structures like bulkheads and nature-based approaches like living shorelines.

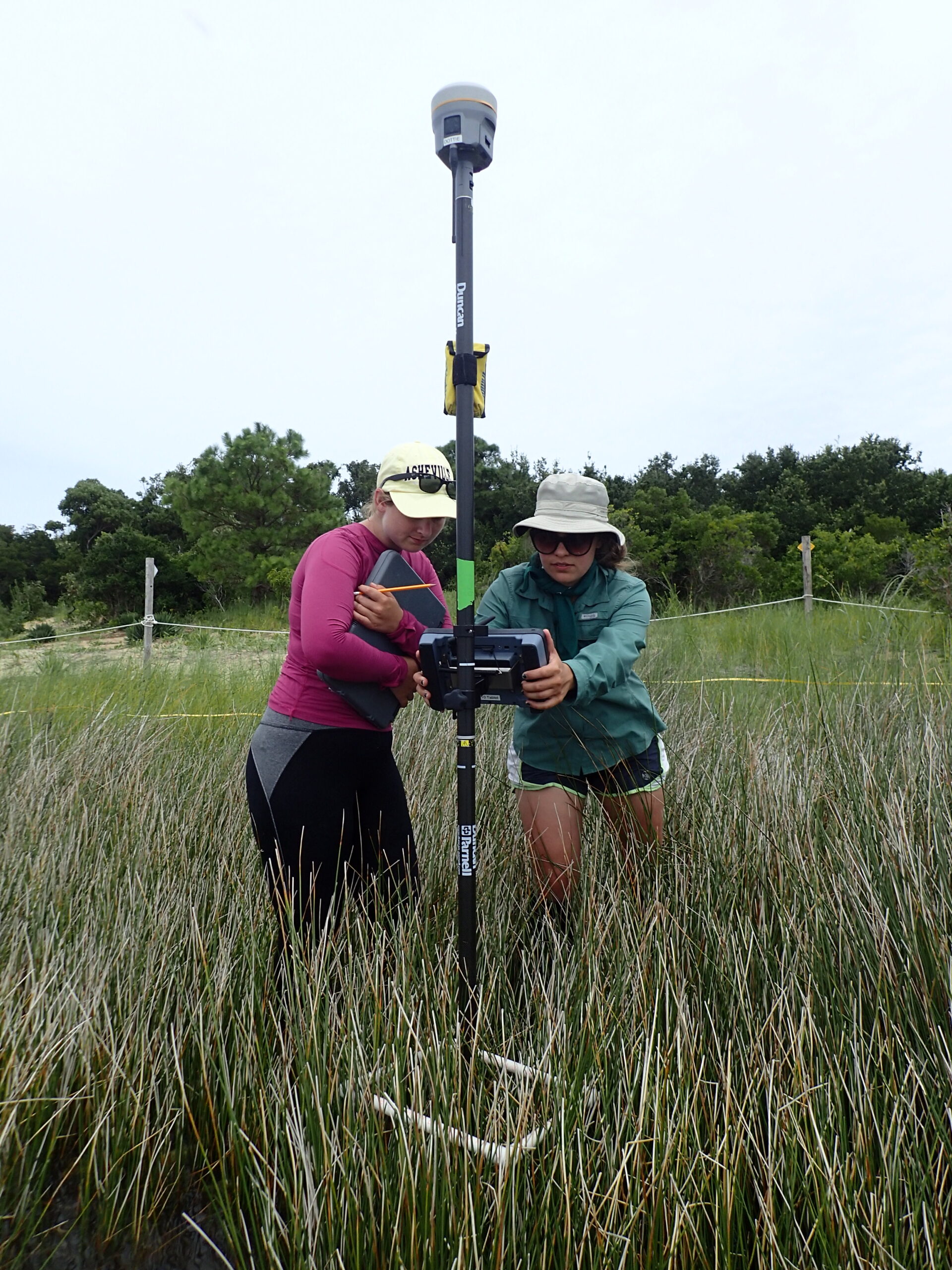

Graduate students Emory Wellman (East Carolina University) and Kelsey Beachman (UNC Wilmington) use a real-time kinematic-GPS unit to collect high resolution elevation data at a rock sill living shoreline. Elevation data can help scientists better understand whether the marsh is growing.

“Effective shoreline management strategies are essential to preserving our intertidal zones in North Carolina,” says Devon Eulie, a coastal scientist at University of North Carolina Wilmington’s Coastal and Estuarine Studies Lab (CES) who is leading a multi-campus team to explore how living shorelines influence the intertidal zone. “In our state, intertidal zones provide ecological and economic benefits by supporting our commercial and recreational fisheries and are crucial to storm protection.”

Living shorelines incorporate native vegetation and, in some cases, low-lying sill or breakwater structures, to protect saltmarsh habitat and shorelines. Nature-based management approaches like living shorelines maintain the interface between land and water, protecting valuable intertidal habitat used by 90% of North Carolina’s commercial and recreational fisheries.

In contrast, traditional hardened shoreline management methods, like bulkheads and revetments, cut off the interaction of land and sea, resulting in the loss of valuable intertidal habitat. Hard structures also increase erosion, reduce biodiversity, and are more costly to install and maintain.

To date, research on living shorelines shows that they provide many benefits that hard shorelines do not. However, there is still much to learn about the best ways to manage eroding coastlines, as well as the implications of different designs and placement of nature-based approaches.

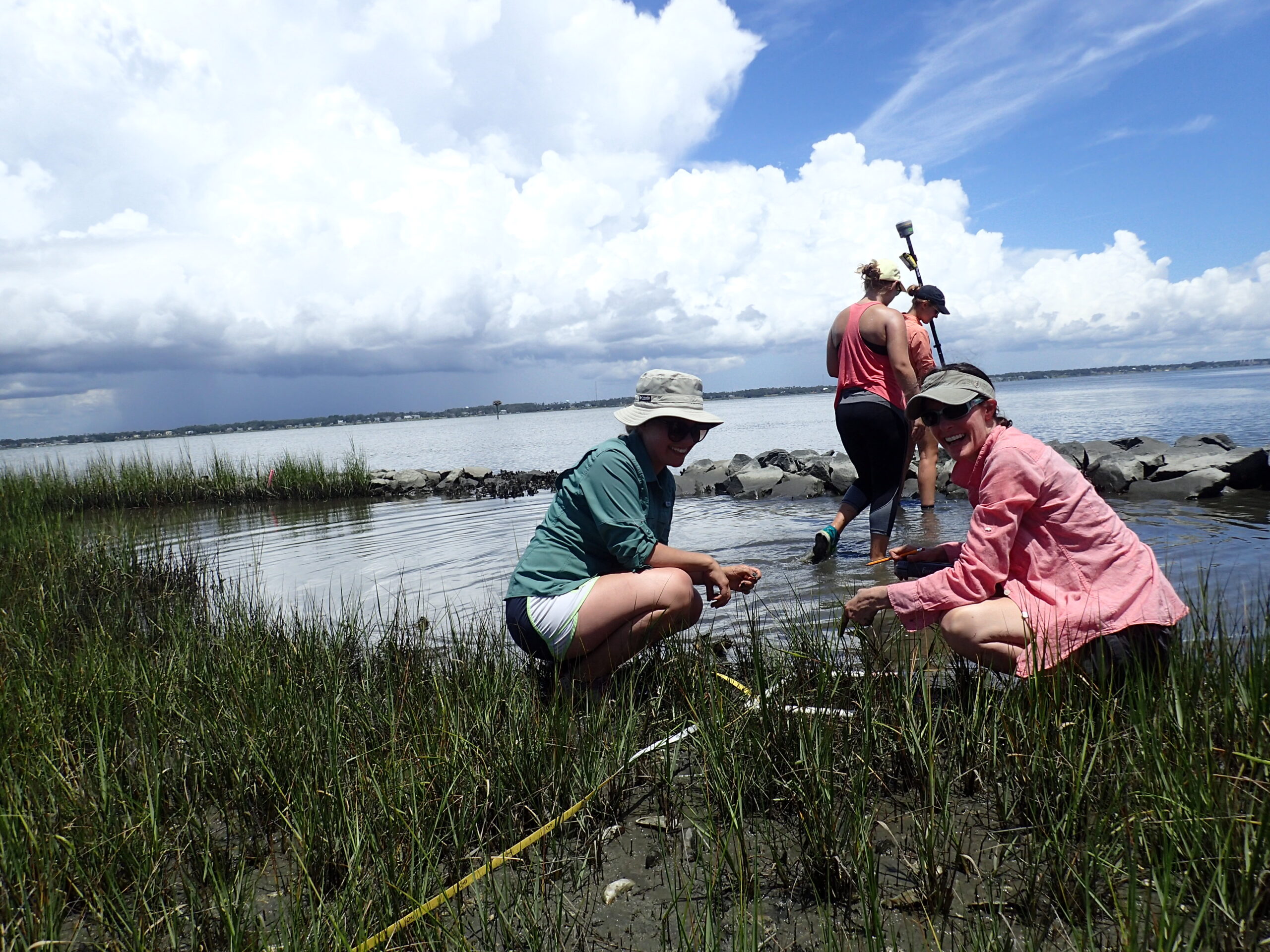

Graduate student Mackenzie Taggart (UNC Wilmington) and coastal technician Kari Signor (UNC Chapel Hill) survey salt marsh vegetation at a rock sill living shoreline. Vegetation data helps scientists understand the health of the marsh.

With support from North Carolina Sea Grant, Eulie and her team have used geospatial science to investigate the benefits and drawbacks of shoreline management decisions across time and place. By collaborating with Rachel Gittman at East Carolina University and Carter Smith at Duke University, they also have used social surveys to understand the impacts of coastal management decisions on residents of North Carolina’s 20 coastal counties.

“Gathering perspectives and information about coastal residents and their communities is essential to grasp the real needs of those who live along the coast,” Eulie explains. “Their responses have given us a greater insight into the emergent risk faced by our community members because of changes in sea level and the increasing frequency and magnitude of storms.”

Graduate student Mackenzie Taggart (UNC Wilmington) and Kelsey Beachman (UNC Wilmington) use a real-time kinematic-GPS unit to collect high resolution elevation data at a rock sill living shoreline. Elevation data can help scientists better understand whether the marsh is growing.

After Hurricane Florence in 2018, the team received a complimentary National Science Foundation Rapid Response Research Grant to expand their Sea Grant study to also understand the immediate impact of hurricanes on North Carolina shorelines. Moreover, the study evaluated how socio-environmental factors, such as community representation and socioeconomic status, have influenced the impact of such a sizable storm on members of the community, as well as on the community as a whole.

Eulie’s lab has found that living shorelines with sills perform well in various site conditions and sill designs. Results emerging from CES work, with support from North Carolina Sea Grant and the UNC System NC Policy Collaboratory Grant, have found that a wide range of living shoreline designs are less likely to experience lateral erosion than sites with no marsh management. They have found that oyster bag sills and rock sills both provide wave dampening protection reducing the loss of marsh habitat. The findings of their work are anticipated to be published this year.

Student-led research and much of the groundwork of this research were done by students from UNC Wilmington, UNC Chapel Hill, and East Carolina University. In fact, the research that Eulie’s lab conducted on North Carolina Sea Grant funding led to an award from the U.S. Coastal Research Program to support Ph.D. student Mariko Polk’s in-depth study on how living shorelines facilitate multiple ecosystem services.

PhD student Mariko Polk (UNC Wilmington) uses a real-time kinematic-GPS unit to collect high resolution shoreline positional data. Polk uses this data to determine how the shoreline is changing over time.

“Our students represent the best and brightest future leaders in research, management, and conservation of our coasts,” says Eulie. “They will be the ones leading our state in the future and it is critical they deeply understand the issues our coasts face.”

The findings from their research will be used to inform homeowners on what approaches may be best for the conditions of their shoreline and to inform policymakers on ways to expand current management to align with new scientific findings.

Eulie believes low-cost community science approaches could be the next step to enable future shoreline monitoring and provide larger datasets on North Carolina’s coasts, as well as engaging residents in developing sustainable shoreline management strategies. Polk agrees. She is leading field data collection and analysis, in collaboration with organizations along the coast.

“By working with coastal managers and understanding the needs of our coastal community members, our lab’s research hopes to build synergy between the need to protect our coastal communities from hazards and protect the environments they are part of,” Polk notes.

If you are an organization or waterfront homeowner who is interested in working with the UNCW CES Lab, please contact them at ceslab@uncw.edu.

Shannon Pelkey received her dual master’s in Environmental Studies and Public Administration from UNCW. She currently serves as marketing coordinator for the Arts Council of Wilmington and plans to pursue a career in environmental nonprofits or sustainability in higher education.