Can We Monitor Juvenile Shrimp With Microchips?

Scientists test a new technology that’s similar to your car’s EZ-Pass in order to track individual shrimp.

Research Need

The ability to track individual animals in coastal and ocean waters has transformed our understanding of animal movement and behavior, as well as the processes affecting animal populations, such as migration, survival, and growth.

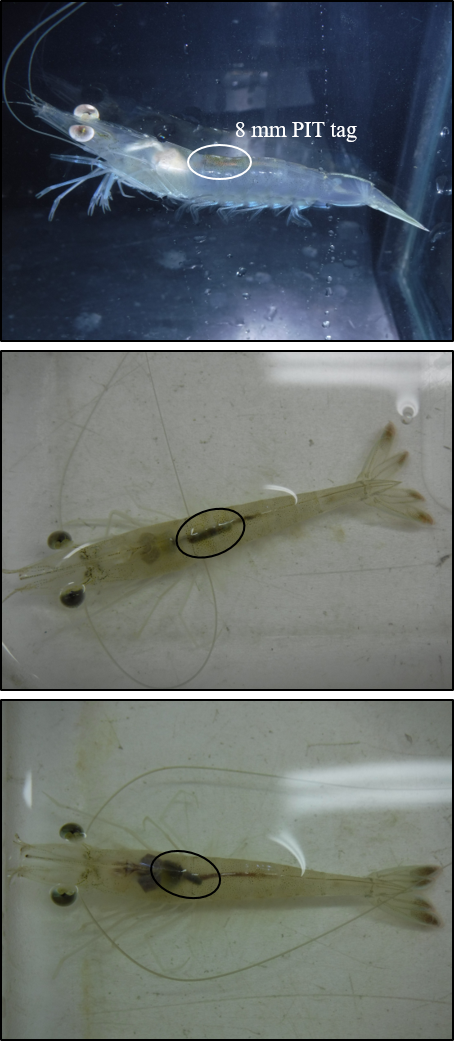

Passive-integrated transponder (PIT) tags are a common tool to track smaller marine animals. Similar to the technology behind your car’s EZ-Pass or pet’s microchip, these small microchips require no power but encode a unique identification number that a handheld device can read. By attaching or injecting the tag into an organism, scientists can non-lethally monitor the same animal over time.

In estuaries, PIT tags have successfully tracked small fishes, like mummichogs and juvenile red drum, but to our knowledge no one had tried them with any size of white shrimp (Litopenaeus setiferus). Because of their economic and ecological importance, we set out to test PIT tags on juvenile white shrimp.

What did we study?

We studied the growth, survival, and feeding behavior of shrimp injected with 8-millimeter PIT tags compared to untagged shrimp.

We collected shrimp from a tidal creek and checked each shrimp daily for survival, and we measured and weighed all the shrimp weekly.

After a month, our team provided different amounts of prey (grass shrimp) to a handful of tagged and untagged shrimp, and we recorded the number of prey they ate within a 12-hour period.

What did we find?

We saw no difference between the tagged and untagged shrimp in their survival rates, their growth, and the amounts of prey they consumed.

What else did we find?

All tagged shrimp retained their PIT tags despite each shrimp molting — shedding and regrowing their hard exoskeleton shell — at least once during the experiment.

So what?

By demonstrating that these tags can be effective, we have a new tool to study the movement, behavior, and ecology of juvenile shrimp in our salt marsh creeks and estuaries.

Specific areas for future research include investigating the impacts of diseases — such as black gill — on white shrimp, as well as testing the relative importance of specific types of habitat in estuaries in the Southeast for juvenile white shrimp.

Reading

Dunn, Robert P, Pfirrmann, Bruce W., and Kimball, Matthew E. (2021). Juvenile white shrimp (Litopenaeus setiferus) can be effectively implanted with passive integrated transponder tags. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 540:151560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2021.151560

Funding for Robert Dunn was provided by the Office for Coastal Management, within the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, via the operations award to the North-Inlet Winyah Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve

Robert Dunn (left) is the research coordinator at the North Inlet-Winyah Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve and a research assistant professor at the University of South Carolina. Bruce Pfirrmann (center) is the research resource specialist at the University of South Carolina’s Baruch Marine Field Laboratory in Georgetown, S.C.. Matt Kimball (right) is the assistant director of the Baruch Marine Field Lab and a research associate professor. All three study authors share an interest in marine and coastal ecology, with specific interests in the population dynamics, habitat use, and behavior of estuarine fishes, shrimps, crabs, and other invertebrates.

Summary compiled by Bruce Pfirrmann and Robert Dunn.

Lead photo: adult white shrimp (Litopenaeus setiferus), courtesy of NOAA.

The text from Hook, Line & Science is available to reprint and republish at no cost, but only in its entirety and with this attribution: Hook, Line & Science, courtesy of Scott Baker and Sara Mirabilio, North Carolina Sea Grant.

- Categories: