Can the Sounds of Courting Fish Help Predict the Number of Offspring?

South Carolina scientists compared underwater fish sounds and environmental data with the numbers of young fish they collected.

The calendar recently turned to fall, and with that comes cooler days and falling water temperatures in the coastal Carolinas. That also means it’s time for red drum — North Carolina’s state saltwater fish — to aggregate, spawn, and produce its next generation.

Research Need

The family Sciaenidae includes red drum, black drum, silver perch, and spotted seatrout, among other fish. A defining characteristic of the drum family is the ability to create throbbing or croaking sounds by using special muscles to vibrate against the swim bladder. Each species makes a slightly different sound.

We’ve long known that these fish produce sounds that are associated with courtship behavior and spawning. In recordings, scientists can determine whether there are many fish “chorusing” — singing together — or individual fish “calling,” where one or more fish may be signaling to potential mates.

If you’ve ever caught and handled a fish from this family — including its other species like spots and croakers, for example — you have likely heard and felt the constant throbbing and drumming sounds and vibrations while holding them.

By listening to recordings of the different species’ calls and choruses, scientists have been able to identify approximately when and where specific spawning aggregations occur. But scientists have a poor understanding of whether fish mating sounds can predict the location, timing, and numbers of their offspring later in the year.

In the simplest terms, do louder and longer fish courtship sounds result in more spawning activity and thus more offspring? And importantly, how do environmental factors affect this?

What did they study?

From February 2013 to December 2018, scientists used passive acoustic recorders to record fisheries soundscapes of red drum, black drum, silver perch, and spotted seatrout in the May River on coastal South Carolina. In addition to sound recordings, scientists also collected a host of environmental data.

In the lab, the research team used the sound files to identify species, group them by sound intensity, and determine the timing and intensity of spawning activity for each species.

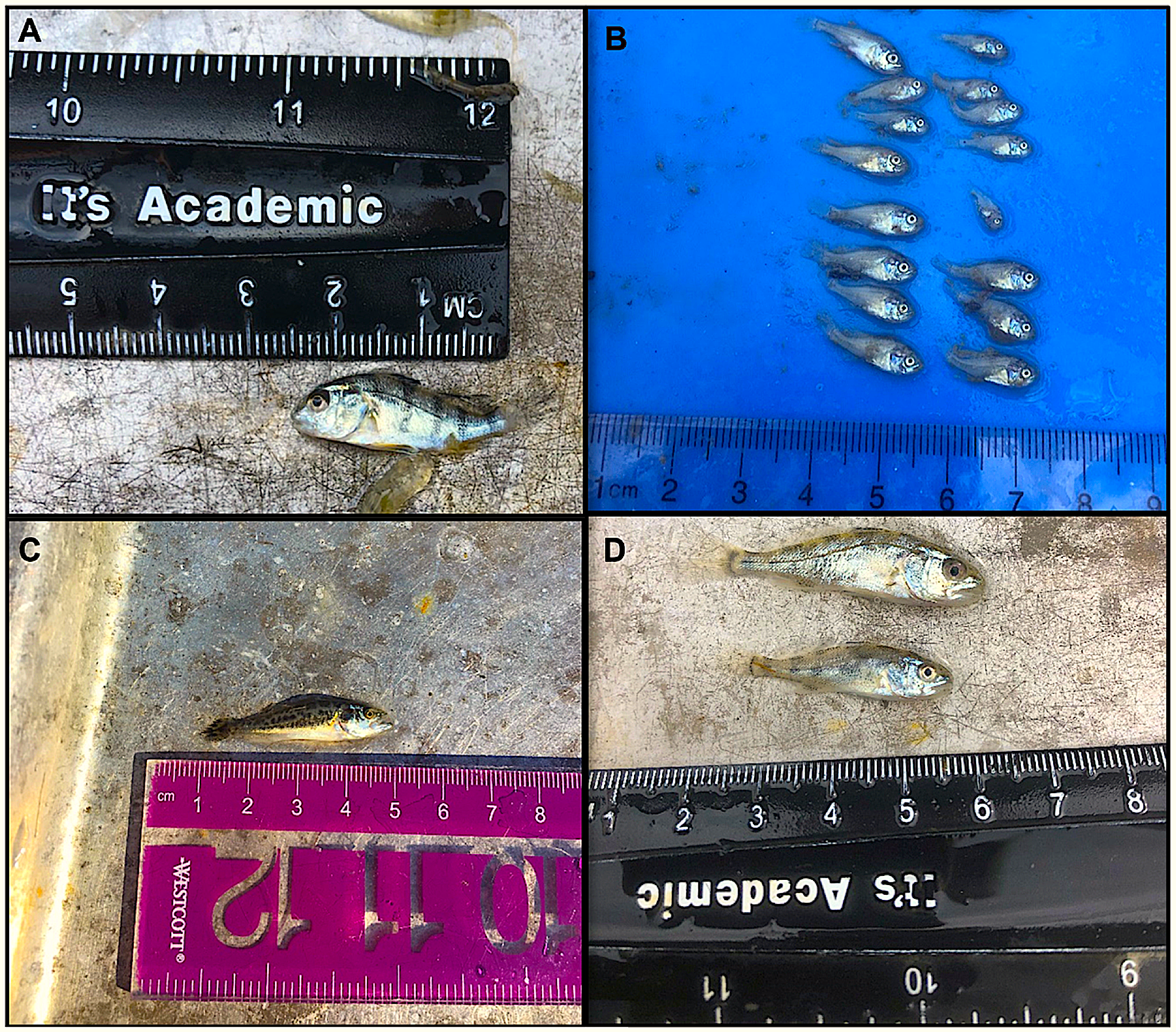

During the last three years of the study, the team used hand-operated nets (“haul seines”) to collect fish once per month at multiple locations near the sound recording stations.

What did they find?

The research team gathered more than 130,000 sound files and captured more than 18,000 recently hatched fish. The vast majority (97%) were silver perch.

Specifically, the timing, duration, and intensity of mating calls and choruses for silver perch, spotted seatrout, and red drum are strongly linked to the seasonal numbers of recently hatched fish.

For spring-spawning fishes (silver perch and spotted seatrout), warmer springs led to a lengthier and more successful spawning season.

Cooler temperatures during the late summer and fall led to similarly high levels of reproductive success for red drum, a fall-spawning fish.

Anything else?

It takes about 30 days for silver perch, spotted seatrout, and red drum to reach 0.5 to 1.2 inches, the size needed to be captured by the nets used.

Interestingly, researchers captured no recordings of black drum spawning choruses during the entire study — only calls from individual fish. With no spawning events documented, perhaps it was no surprise that researchers captured only four black drum offspring in nets during the study.

Can I listen to these fish?

The researchers provide free access to a variety of sound recordings from the study here.

So what?

The study provides evidence that we can use passive acoustics to monitor the reproductive output of some of our most popular inshore sport fishes. Will the next generation of anglers add underwater microphones to their tackle box?

Reading

Monczak, Agnieszka, Bradshaw McKinney, Jamileh Souiedan, Alyssa D. Marian, Ashlee Seder, Eva May, Thomas Morgenstern, William Roumillat, Eric W. Montie. 2022. Sciaenid courtship sounds correlate with juvenile appearance and abundance in the May River, South Carolina, USA. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. Vol. 693: 1–17.

This work was supported by numerous grants including the Palmetto Bluff Conservancy, Research Initiative for Summer Engagement (RISE) grant from the University of South Carolina (USC), the USCB Sea Islands Institute, the Port Royal Sound Foundation, multiple USC ASPIRE internal awards and Magellan grants, an SC EPSCoR/IDeA Program award (#17-RE02), the Lowcountry Institute, the Spring Island Trust, the Community Foundation of the Lowcountry, the Town of Bluffton/Beaufort County, and the Coastal Discovery Museum. This work was also supported, in part, by the Southeast Coastal Ocean Observing Regional Association (SECOORA) with NOAA financial assistance awards (numbers NA16NOS0120028 and NA21NOS0120097).

by Scott Baker

Lead illustration credit: Claire Mueller.

The text from Hook, Line & Science is available to reprint and republish, but only in its entirety and with this attribution: Hook, Line & Science, courtesy of Scott Baker and Sara Mirabilio, North Carolina Sea Grant. HookLineScience.com

- Categories: