Are East Coast Anglers Catching Tunas, Sharks, and Billfishes Farther North?

Trends from a longstanding recreational survey can help anglers, tournaments, and communities plan for changing fisheries.

Research Need

Highly Migratory Species like tunas, sharks, and billfishes are prized by offshore anglers and charter fishing operations. In many communities along the East Coast, fishing for these species is centered around tournaments that, by necessity, are located near the populations of these species and that take place at a time of year when they are most available.

Offshore anglers are skilled at utilizing environmental data to locate the fish, often referring to personal catch histories, changes in sea surface temperatures, and insight from other fishers. But as a more consistent resource, NOAA conducts an annual survey each year that helps us manage these fisheries.

The NOAA Large Pelagics Survey is a specialty survey that spans Maine to Virginia and focuses on the Highly Migratory Species that anglers target from June to October. This survey exists because Highly Migratory Species — unlike nearshore species like flounder, drum, and trout — are considered “rare-event,” and are much less likely to be encountered.

We know that the warming ocean is forcing some species to shift northward, meaning anglers should also be catching Highly Migratory Species farther to the north. Looking at the most recent 18-years of recreational catch data is one way to verify this.

What did they study?

NOAA scientists utilized dockside interview data from the Large Pelagics Survey from 2002 to 2019 to see when and where anglers reportedly caught 12 Highly Migratory Species. Coupled with detailed public records of sea-surface temperature, the team could then use models to determine shifts in captures in relation to latitude, time of year, and water temperature.

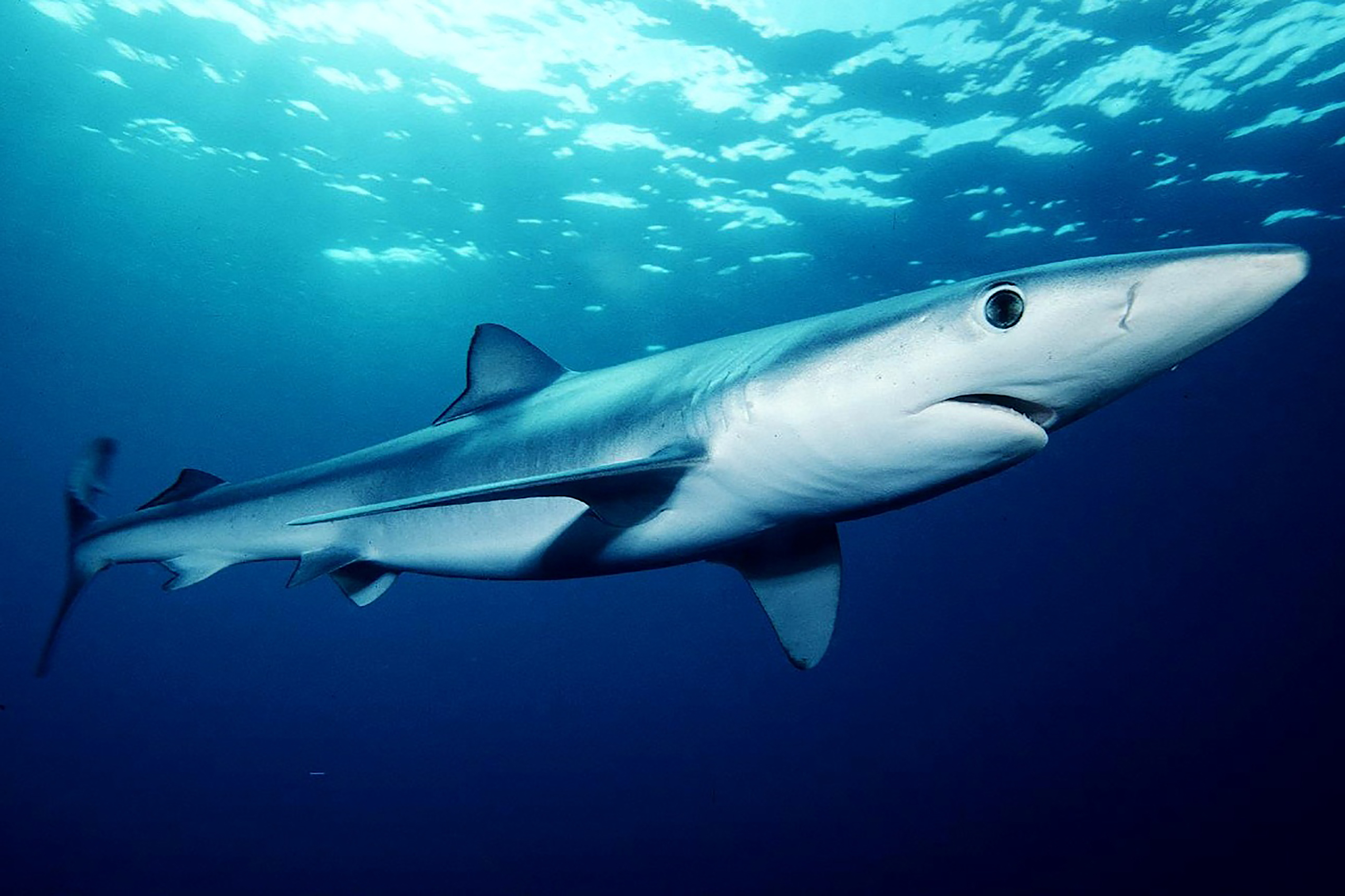

The scientists focused on species of interest to anglers: albacore tuna, bigeye tuna, skip-jack tuna, yellowfin tuna, bluefin tuna (both small and large, coded as different target species), blue shark, shortfin mako shark, Atlantic common thresher shark, Atlantic blue marlin, swordfish, and white marlin.

What did they find?

Scientists looked at more than 96,000 dockside interviews in the dataset, some from Highly Migratory Species tournaments.

Since the earliest year of the study period (2002), the analyses indicate that Highly Migratory Species catch locations have shifted north. Further, many are being captured earlier in the year. These shifts are strongly linked to increasing sea surface temperature.

For example, northerly shifts in capture over the time series ranged from about 0.5 nautical-miles per year for blue marlin to about 5 nautical-miles per year for small bluefin tuna. And for every ~2° F increase in sea surface temperature, species shifted northwards a minimum of 1.5 nautical-miles (large bluefin tuna) to 22 nautical-miles (blue shark).

Anything else?

The most frequently encountered species in the survey were yellowfin tuna (14,326), small bluefin tuna (8,177), and white marlin (7,786).

So what?

The NOAA Large Pelagics Survey was designed to monitor the catch of bluefin tuna during the primary fishing season off the coast of the Northeast U.S., but reanalysis of the data available clearly suggests that the survey provides insight on many Highly Migratory Species important to anglers and communities along the entire East Coast.

Reading

Crear, D. P., Curtis, T. H., Hutt, C. P., & Lee, Y.-W. (2023). Climate-influenced shifts in a highly migratory species recreational fishery. Fisheries Oceanography, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/fog.12632

Funding for the study was provided by the NOAA NMFS.

Summary by Scott Baker.

Lead photo: blue shark, courtesy of Mark Conlin/NMFS.

The text from Hook, Line & Science is available to reprint and republish, but only in its entirety and with this attribution: Hook, Line & Science, courtesy of Scott Baker and Sara Mirabilio, North Carolina Sea Grant. HookLineScience.com

- Categories: