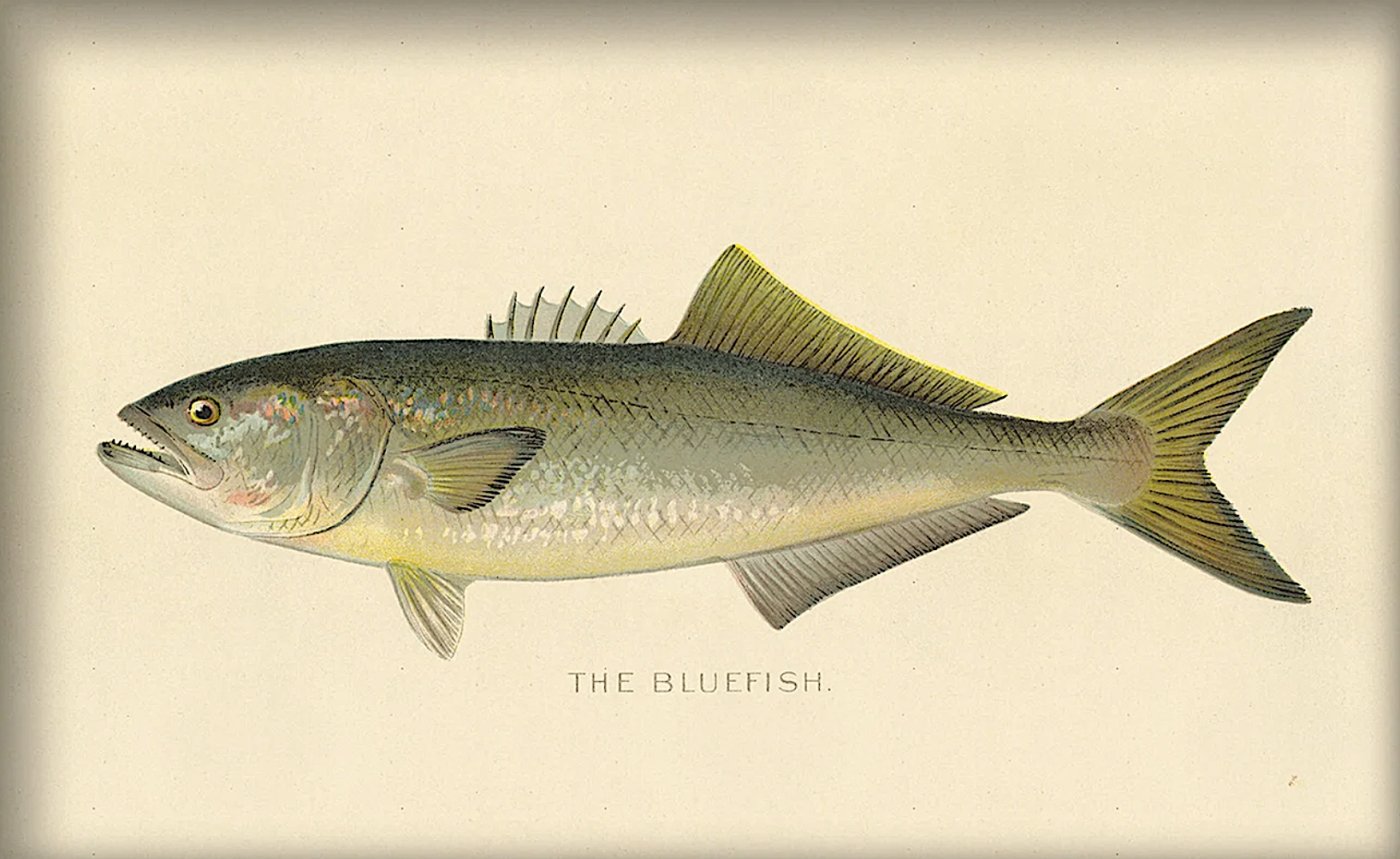

Do Contaminants Affect the Bluefish Population?

Scientists looked at whether PCBs and pesticides are leaving a chemical “fingerprint.”

The weather has started to resemble fall, bringing with it fishing favorites along North Carolina’s coast, including bluefish. During the spring and summer, they make their way north and can be found from Cape Hatteras to the Gulf of Maine. As temperatures begin to cool in the fall, they migrate to their wintering grounds between North Carolina and Florida.

Bluefish will hit just about anything in the water, often in a feeding frenzy commonly known as a “bluefish blitz.” The fish’s hard strike on an angler line means it’ll be a challenging — but fun-filled — fight to land after hooking it.

Yet, in the last few years, anglers have remarked about not seeing large schools of bluefish anymore, and, like fishery biologists, they wonder why there are fewer fish.

Research Need

In 2020, the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries implemented a three-fish possession limit for private anglers. Estimates from the 2019 population assessment had shown that the number of bluefish capable of reproducing has been decreasing since 2008 — and it has remained below a long-term threshold for viability of the species since 2014.

Fishery managers are trying to understand better the factors that affect the size of the bluefish population. For instance, could chemical contaminants play a role?

What did they study?

A research team wanted to know to what extent very young bluefish (those younger than one year of age) accumulated high levels of contaminants in a Mid-Atlantic estuary. They chose the Hudson River Estuary for the site of the study both because of its history of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and chlorinated pesticide contamination and because it regularly serves as habitat for young bluefish.

As a newly hatched fish feeds on local prey, it displays its habitat’s chemical profile in the ear’s “otolith,” which is like a small bone. Using this “chemical fingerprinting,” the scientists examined seasonal and multi-year trends over a 3-year period.

What did they find?

Throughout three spring and summer seasons, the research team captured a total of 358 bluefish within their first year of life. All otolith samples contained some form of PCB.

Other research has shown that bluefish accumulate PCBs rapidly upon entering a contaminated environment due to their rapid growth rate and rapid consumption of prey. In this study, the research team did notice a distinct chemical signature in bluefish as small as 1.8 inches in fork length.

Relating to the array of chemical substances, fish collected from the first two years of the study had similar PCB profiles. The Year 3 profile was different, and the team determined most of the variability (69%) was related to fish size. Even though also under one year of age, Year 3 fish were larger on average.

Seasonally, PCB profiles were similar for comparable weight classes. This suggests that PCB source conditions during bluefish estuarine residency remained consistent throughout each season.

Anything else?

There was no consistent pattern of pesticide accumulation, which varied seasonally and from year to year. Unlike PCBs, which most often pollute from a particular source, pesticides in the Hudson River historically are associated mostly with broader agriculture runoff. The research team feels the significant differences in pesticides in fish samples could be from pesticides used historically yet newly exposed in resuspended sediments.

So what?

A distinct chemical profile develops when bluefish enter a contaminated nursery habitat, which suggests one possible factor that could affect the size of the species’ population.

We don’t yet know the long-term effects of contaminants on bluefish. However, a better understanding of this would help to identify habitat use, as well as to evaluate habitats for the survival of bluefish — and other commercially or recreationally harvested fish — at different stages of their development.

Reading

Williams, S.D., and McCrary, J.P. (2021) Temporal organochlorine profiles in young-of-the-year bluefish (Pomatomus saltatrix) in the Hudson River Estuary. Marine Pollution Bulletin. Volume 165, 112128, ISSN 0025-326X.

This research was supported, in part, by the NOAA Educational Partnership Program with Minority Serving Institutions Graduate Program of the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through the US Departments of Commerce and Energy. Title III of the Department of Education provided additional funding. Several sampling efforts were made in collaboration with the New Jersey Marine Science Consortium and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.

By Sara Mirabilio.

Lead photo credit: Library of Congress.

The text from Hook, Line & Science is available to reprint and republish at no cost, but only in its entirety and with this attribution: Hook, Line & Science, courtesy of Scott Baker and Sara Mirabilio, North Carolina Sea Grant.