Do Self-Releasing Hooks Minimize Fish Injuries During Catch-and-Release?

A bite-shortened hook, designed to release fish without handling, shows promise.

Spotted seatrout are harvested throughout the year, with two peaks in landings: October through February and April through May. So fall means many anglers are targeting the species.

Fishermen seeking spotted seatrout use hook-and-line gear with a variety of natural and artificial baits. Fishing practices and gears that minimize hook injury, handling, and air exposure can considerably improve the chances for the survival of released fish.

Research Need

Releasing fish can help conserve their populations, but the process of capturing and handling fish also can result in injuries or death. These “discard effects” present a major conservation issue in recreational fisheries. Even if the percentage of injuries and mortalities are relatively small, fisheries where large numbers of fish are released can have cumulative discard effects that impact the population.

Fishing practices and gears that minimize hook injury, handling, and air exposure can considerably improve the chances for survival of released fish. In particular, efficient dehooking substantially reduces the physiological stress in fish that typically occurs during the landing and release process.

Earlier field trials with bonefish on Palmyra Atoll found fish would “spit out” bite-shortened hooks once they were reeled in toward the angler and the angler gave slack in the fishing line. The idea appeared promising and prompted the researchers at the UF/IFAS Nature Coast Biological Station to begin more rigorous testing.

What Did We Study?

To our knowledge, these are the first assessments of hooks designed to self-release from fish and fully eliminate fish handling.

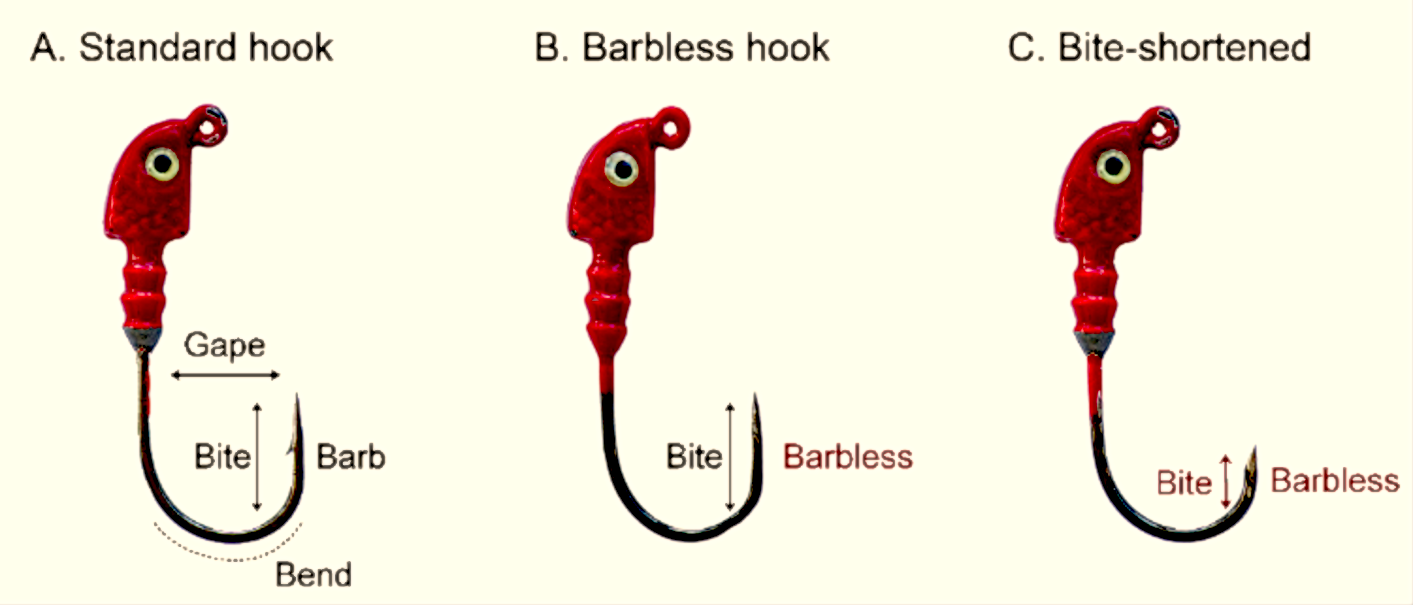

On 150 spotted seatrout, we tested whether standard, barbless, or bite-shortened hooks (Figure 1) would allow anglers to reel in the popular coastal sport fish and then allow the fish to self-release from the hook while still in the water.

What Did We Find?

We found promising results for the bite-shortened modified hook, which enabled anglers to land 91% of hooked spotted seatrout and then release 87% of those fish without direct handling. In comparison, the self-release success rates were 47% using barbless hooks and 20% using standard, unmodified hooks.

We also found that smaller fish were able to be self-released without handling at higher rates. Length-regulated fisheries often protect smaller fish, and reducing mortality in these fish especially can help conserve resources.

So What?

A proven and effective self-releasing hook could have broad conservation and management applications in recreational fisheries as a means to minimizing or eliminating injuries and mortalities in catch-and-release fishing. A foreseeable use of self-releasing hooks could be to allow restricted fishing in sensitive fishing areas, such as no-take aquatic protected areas or areas experiencing unsustainable fishing pressure. Further research with different lures, species, and anglers can inform conservation strategies.

Reading

Harris, H. E., Whalen, B. K., Gude, A. G., and Allen, M. S. (2021). Testing a Bite-Shortened Hook to Minimize Fish Handling in a Recreational Fishery. Fisheries, 1–8. doi:10.1002/fsh.10608.

By Holden Earl Harris, a former dive instructor and commercial spearfisher and current postdoctoral research associate at the University of Florida’s Nature Coast Biological Station. He works to apply integrative research and quantitative ecology to guide natural resource management. His focus areas include commercialized invasive species harvest and the developing lionfish fishery; innovative fisheries gear, including deepwater lionfish traps and self-releasing fishhooks; and, applying ecosystem models to understand and forecast the effects of land-use and climate changes to estuarine communities.

Lead photo courtesy of UF/IFAS Nature Coast Biological Station.

The text from Hook, Line & Science is available to reprint and republish at no cost, but only in its entirety and with this attribution: Hook, Line & Science, courtesy of Scott Baker and Sara Mirabilio, North Carolina Sea Grant.

- Categories: