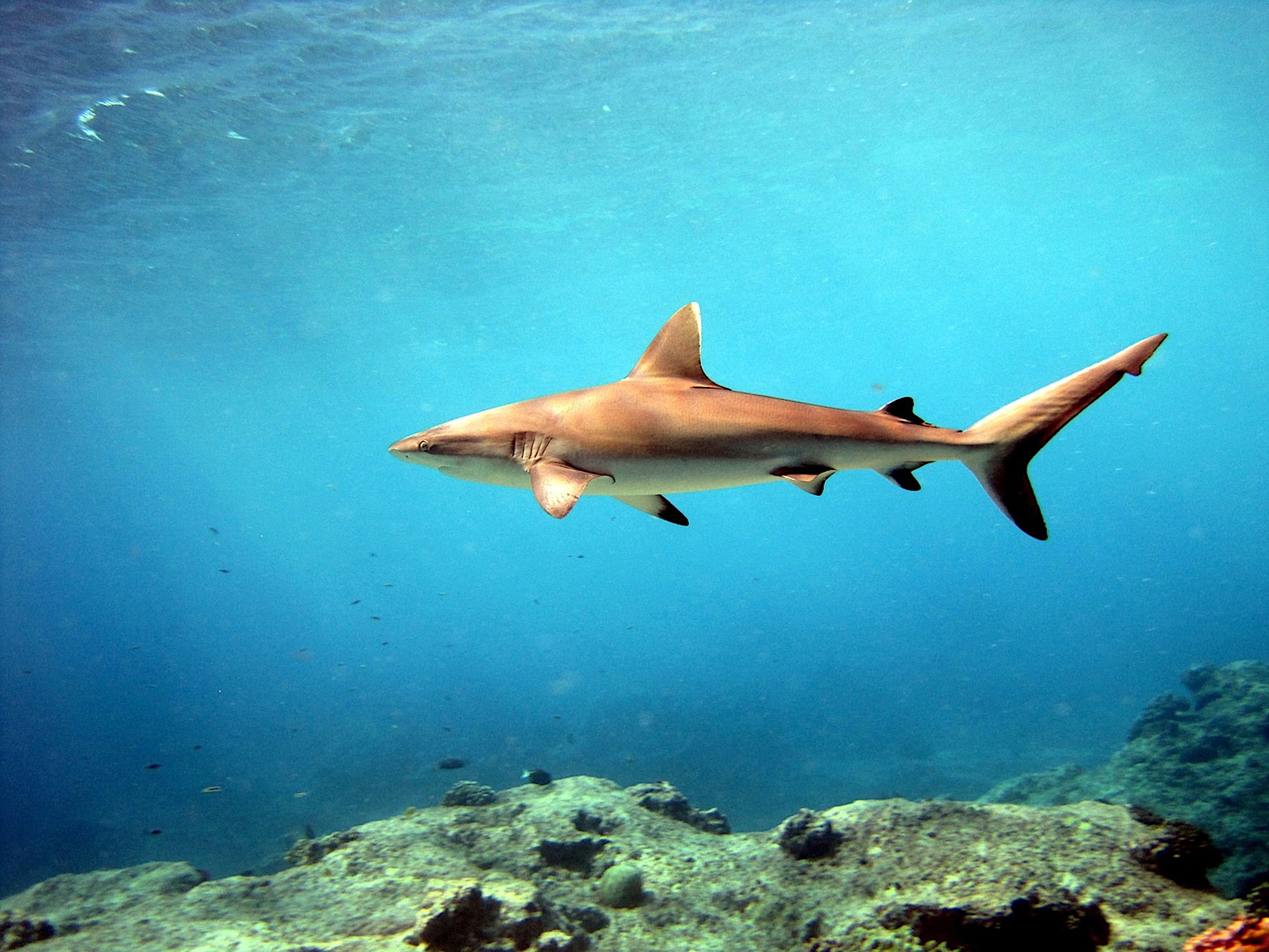

How Often Do Sharks Swipe the Catch?

A new study reveals that avid anglers are no strangers to opportunistic sharks — and this could impact shark conservation.

Many species of shark are found year-round off the North Carolina coast, but several open-ocean species will venture closer to shore come early spring. This can either provide the thrill of a big fight for these catch-and-release species or cause dismay over the loss of bait and gear — or, even worse, cause dismay over losing prize fish catches to hungry sharks.

Research Need

“Shark depredation” — when a shark takes part or all of a hooked fish before an angler or commercial fisher lands it — is increasing in the United States, according to anecdotal reports.

Most research on perceptions of sharks has focused on people whose livelihoods depend on the fish they catch (or don’t catch, thanks to the sharks). But do anglers’ experiences with sharks impact their support for shark conservation? Is the rise in recreational shark fishing in any way correlated to personal experiences and second-hand accounts from friends and family?

What did they study?

A research team set out to study the impact of sharks on recreational fishing experiences, using an online survey of saltwater anglers in North America.

The team gathered information about anglers’ emotional and behavioral responses to shark depredation, as well as basic information about the survey participants, including how often they fish, where they fish, and species they target. The surveys also collected information about anglers’ motivations for fishing (such as for food or catch-and-release), whether they have experienced depredation, their perceptions of sharks and shark conservation, and whether they served as a fishing guide.

Anglers who had experienced depredation in the last five years also received specific questions about those events.

What did they find?

Most of the anglers who took the survey were male (89%), between the ages of 25 and 44 (51%), and considered themselves avid anglers (68%) who fish more than 30 times a year. Of the 541 people who responded, 77% had experienced depredation in the last five years, more commonly in the Southeast than other areas.

Of those anglers who experienced shark depredation, 90.3% had experienced it more than once, and over half experienced 20 or more depredation events in the last five years.

The most frequently depredated fish included various tuna species, king mackerel, and various snappers, though these numbers primarily are due to the large number of respondents from the southeastern U.S., particularly Florida.

In the northeast, the most frequently depredated species were striped bass, black sea bass, and pollock, and, on the West Coast, anglers most frequently reported that sharks took tunas.

Anything else?

The team determined significant differences in emotional responses to depredation between fishing guides and anglers. Guides felt negative emotions — including sadness, distress, and anger — much more extremely than anglers. Additionally, guides reported feeling excitement or awe less than anglers.

All told, 87% of guides experienced depredation when fishing with clients and overwhelmingly reported that depredation has a negative effect on their livelihood.

So what?

While many anglers reported that they would not change their behavior after experiencing depredation, guides said they were much more likely to target and harvest sharks in the future, as well as much less likely to fish in the same area again.

Such behavior change — to target and harvest sharks recreationally — results in the potential for shark depredation to have lasting management implications both for the species anglers target and for shark populations.

Reading

Casselberry, G.A., Markowitz, E.M., Alves, K., Russo, J.D., Skomal, G.B., and Danylchuk, A.J. 2022. When fishing bites: Understanding angler responses to shark depredation. Fisheries Research, 246:106174.

By Sara Mirabilio

Lead photo credit: NOAA.

The text from Hook, Line & Science is available to reprint and republish at no cost, but only in its entirety and with this attribution: Hook, Line & Science, courtesy of Scott Baker and Sara Mirabilio, North Carolina Sea Grant.