How old is that fish — and why does it matter?

NOAA Fisheries scientists can estimate a fish’s age by analyzing ear bones, scales, or spines.

Research Need

In the Southeast, few activities are as culturally or economically significant as fishing. From commercial seafood at local markets to enthusiasts investing in gear to recreationally fish, it is easy to see how valuable a healthy fish population is to the economy.

NOAA Fisheries provides the science and management advice to ensure long term viability of this natural resource. NOAA port agents visit fish houses to sample recent commercial catches, and dockside agents review recreational headboat trips to understand what they caught. Some of the data they collect include the types of fish, lengths, weights, locations, and effort (the amount of time spent fishing).

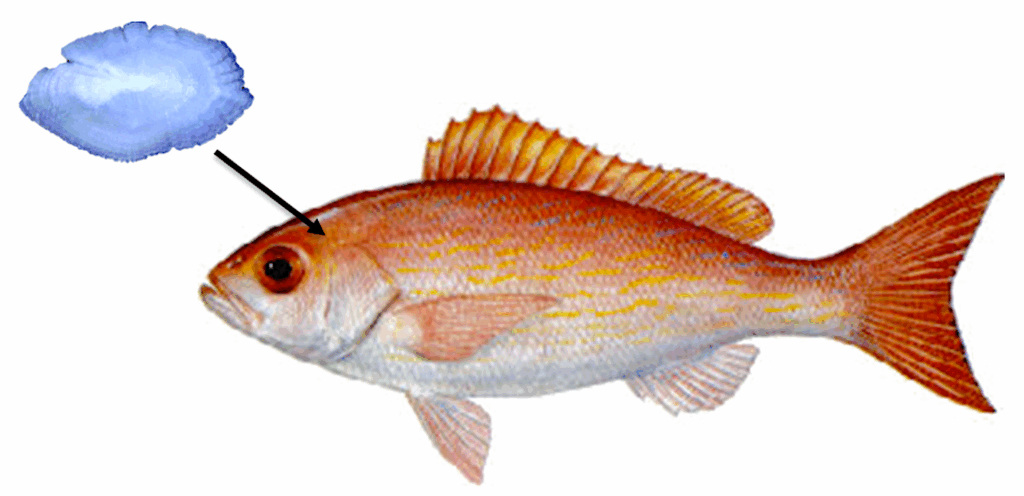

To estimate the ages of fish, NOAA’s age and growth program at the Southeast Fisheries Science Center uses samples, such as fish scales, otoliths (ear bones), or spines. All these data help NOAA to understand fish populations, which better informs stock assessments and allows for sustainable fishing and conservation.

What do we study?

NOAA has been collecting otoliths and ageing fish in the Southeast since the mid-1970s. We have a huge inventory of samples from various locations that has allowed us to research the traits of valuable species over their life histories. Some of our data sets contain tens of thousands of samples, or even more.

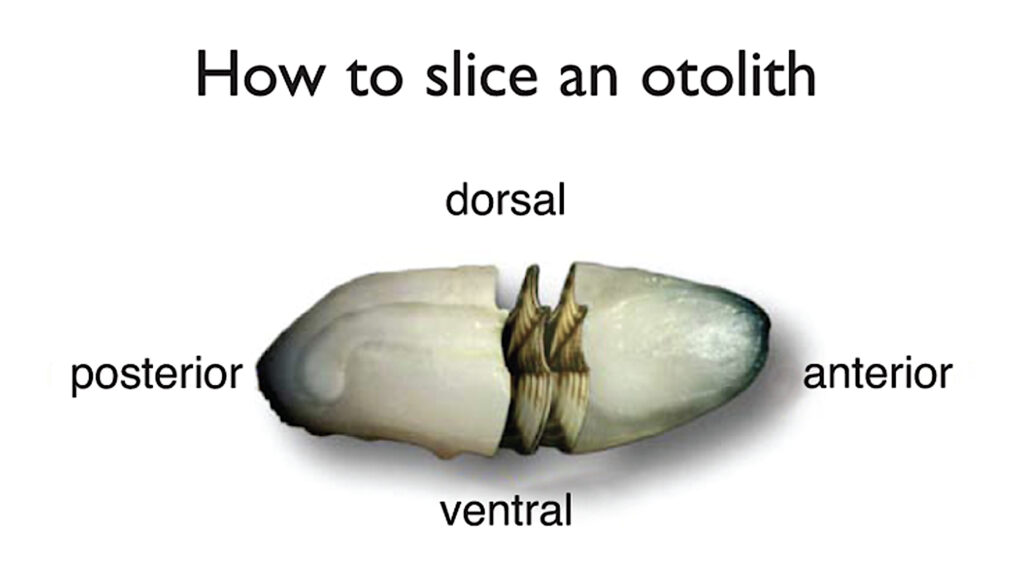

Fish hard parts can help us estimate the age of fish because they lay down annuli, or rings (similar to tree rings) for each year they live. Fisheries scientists take a thin slice out of the middle if necessary (depending on the species), and count the number of rings under a microscope.

The age data collected by NOAA, in combination with data from universities or state fisheries agencies, supply information to models that estimate fish populations (stock assessments).

By linking the ages of fish to their sizes, stock assessors can track strong recruitment years (years where more fish survived to older ages) or estimate growth rates. That information then informs decisions on management measures (such as limits on minimum fish size or the number of fish allowed to be kept) for commercial and recreational fisheries.

What have we learned?

Would you believe that some of those fish you catch can be up to 50 years old, like red snapper, or close to 70, like snowy grouper? Imagine what they have experienced over such a long period of time.

No two otoliths are the same between species, either. Large pelagic fish, such as those from billfish from the Famous Big Rock tournament, have small, delicate otoliths. Meanwhile, red drum have huge stone-like otoliths.

The reason for this? Otoliths serve a few different purposes, including tracking sounds and helping fish maintain equilibrium (similar to human ears). For instance, fish on reefs or in shallow water need to hear better to avoid becoming prey and to find food easier, and they also need to maintain their balance relative both to the sea bottom and their more complex environment.

On the other hand, large fish higher in the water column are constantly moving through open water and can escape easier, while not usually needing to avoid swimming into obstacles due to a lack of balance.

Anything else?

We rely on anglers for most of this valuable information. If a dockside agent approaches you, sharing information about your catch can help us better understand fish populations and provide more accurate and responsive scientific advice for fisheries managers. As the old fishing proverb goes, “Counting fish is like counting trees, except they are invisible — and they move.”

Therefore, the more data we can gather from anglers, the better our science will get, protecting a valuable natural resource for the economy — and for your enjoyment.

Andy Ostrowski (below) is a fisheries biologist with NOAA Fisheries, Southeast Fisheries Science Center in Beaufort, North Carolina. Read more about him here.

The text from Hook, Line & Science is available to reprint and republish at no cost, but only in its entirety and with this attribution: Hook, Line & Science, courtesy of Scott Baker and Sara Mirabilio, North Carolina Sea Grant.

- Categories: