Danielle Keller is the 2016 N.C. Coastal Research Fellow. Courtesy Danielle Keller

It’s the time of year when holiday music is everywhere. In the grocery stores, at the bank, maybe even in your car — it’s hard to escape. While I was driving recently, the song “White Christmas,” sung by Bing Crosby, came on my radio.

Being a nerdy ecologist, I couldn’t help but wonder what some juvenile gag groupers and gulf flounders might be thinking about this holiday season. I imagined they might be singing their own version of this song that goes something like:

“I’m dreaming of a green grass bed, just like the ones I used to know.”

Because it’s winter now, juvenile fishes and crabs likely are missing their main nursery habitat in which they grew up during the summer. Did you know seagrasses are affected by seasons just like terrestrial ecosystems? Tree leaves change color in the autumn and eventually fall off. Similar seasonal shifts can be found in habitats like seagrasses.

When water temperatures get too hot in the summer, some seagrasses naturally begin to degrade and decompose into the sediment. However, like trees budding new leaves in the spring — only occurring a little earlier — seagrasses will start growing back over winter. They will reach their peak cover in mid-summer. That’s when new juvenile fishes and crabs settle to those beds to use them as a safe place to find food and hide from predators.

These processes and interactions really interest me. As a doctoral student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Institute of Marine Sciences, I have been working to better understand how changes in seagrass species across seasons affect the habitat use of juvenile fish and crabs — also known as nekton — in our coastal waters. I was able to conduct field research through a fellowship from North Carolina Sea Grant and N.C. Coastal Reserve and National Estuarine Research Reserve Program.

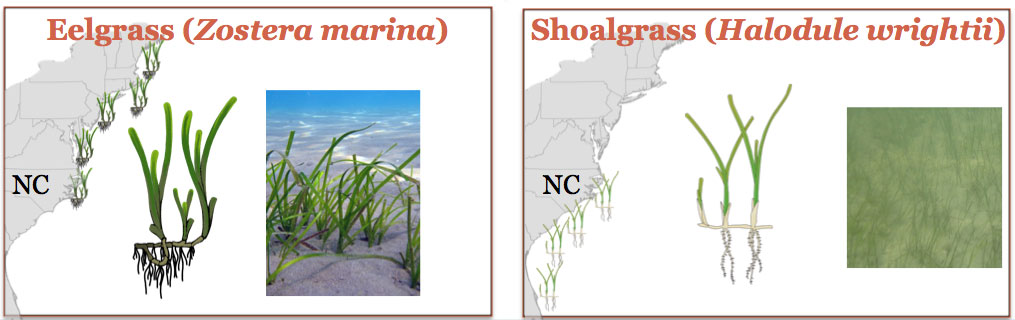

Did you know North Carolina supports more submerged aquatic vegetation than any other state along the Atlantic Coast, except for Florida? The dominant seagrass species in our state, eelgrass (Zostera marina) sits at its thermal tolerance and southern geographic limit, so temperature increases may be particularly problematic here. As eelgrass cover declines, shoalgrass (Halodule wrightii), a shorter seagrass species with less dense shoots and thinner leaves, becomes more prominent. Shoalgrass can tolerate much higher temperatures and shallower depths, but it potentially supports fewer organisms associated with seagrass.

Appearance and distribution of eelgrass (Zostera marina) and shoalgrass (Halodule wrightii). Courtesy Danielle Keller

Why is this important to you? The global seafood industry supports about 10 to 12 percent of the world’s population — landings are worth 80 to 85 million tons per year since 1990 — according to a study reported in the Environmental Resource Economy Journal in 2012. A profitable and favorable seafood industry depends on healthy fish habitats, because many of our ecologically and economically important fish and seafood grow up in estuaries. Essentially, we owe it to these nursery habitats for all the delicious seafood we order in restaurants. Fully understanding these systems greatly contributes to the productivity of many commercially and recreationally important species.

You don’t eat seafood: Is this still important to you? Yes! Nursery habitats are incredibly important because they provide other irreplaceable services, like protecting our coasts and homes from storms, filtering harmful chemicals and pollutants from the water, and trapping sediments and nutrients. Additionally, they provide juvenile fishes some lyrics for their holiday carols.

So how does this work? This project has been particularly exciting to me because we can track fish underwater with the latest technological advances. Fishermen wonder all the time where the fish are, and so do the scientists. By using underwater hydrophones, we can hear where the fish are in order to figure out which nursery habitats are important to them, as well as how those choices change seasonally. It’s a nerve-racking process because it’s not like monitoring a tree that will always be in the same position after you take your measurements. Rather, fish are constantly moving. Once you release a fish back into the estuary, you may never see or hear from it again.

LEFT: These listening devices are attached to sand screws, which can securely anchor the devices below the water for 6 to 12 months. RIGHT: We implanted these acoustic tags into the fish we captured. Photos by Danielle Keller

So, where do the fish go? What habitats do they use in the winter? To answer these questions, we deployed an array of 21 listening devices located in seagrass beds at seven sites located around the Rachel Carson National Estuarine Research Reserve in Beaufort, North Carolina.

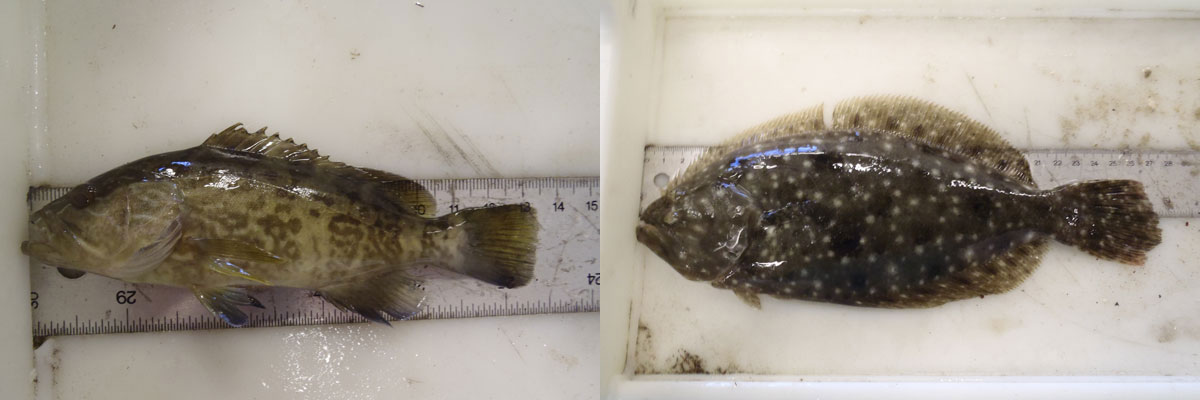

Gag grouper and gulf flounder acted as our model species because we know that they rely on the seagrass beds where we conducted our study. Fish were caught throughout the summer, as the babies settled in the estuary and became large enough for tagging. We surgically implanted an acoustic transmitter into each fish. After a 24- to 48-hour recovery in the lab, fish were released back into the grass bed where they had been caught. That’s right, as a marine ecologist you are not only a fish finder, but fish doctor and fish conservator, as well.

We are studying gag grouper (left) and gulf flounder (right). Photos by Danielle Keller

The tag emits a pulsed chirp unique to each fish in order to identify the presence of individual fish within range of a listening device. Data collected from detected fish will be used to calculate the duration those fish reside within seagrass beds as water temperatures increase in summer months and decrease in the winter. The cool thing about this type of data collection is that the listening device is doing the work once you set up the experiment. So when I’m in the car or sitting at home listening to holiday music, data are constantly being recorded. That is, however, if the fish are still in the estuary near our devices, using the once “green” beds that used to be there, but are now more “brown,” consisting of mostly mud bottom.

In October, I had the pleasure of immersing my entire body in very cold water to retrieve data from each listening device. Although I am still shaking from this chilly day, I think we are going to have a pretty interesting story to tell.

Over the next few months I will process 250,000 detections that we received. That number is a good sign that the fish didn’t leave the area soon after we released them, which had been a constant fear in the back of my mind.

Much work is still to be done. I will be making an interactive map to identify where the gag grouper and gulf flounder go as their preferred seagrass species declines or seasonally degrades.

By learning more about the effects of temperature on seagrass species composition and habitat use by nekton, managers can make more effective decisions about habitats to prioritize as managed areas. So not just the fish will be dreaming of green seagrass beds, but so may all the ‘fish investigators’ — and hopefully you will too!

Take a look at my website for more updates on this research and follow me on Twitter at @hioctopi.

Danielle Keller is the 2016 Coastal Research Fellow, supported by North Carolina Sea Grant and N.C. Coastal Reserve and National Estuarine Research Reserve Program. She is a doctoral student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Institute of Marine Sciences. Her research focuses on understanding how structured habitats affect ecological communities at landscape scales — incorporating how species respond across multiple habitats within a system. Read an earlier blog post about her work here.