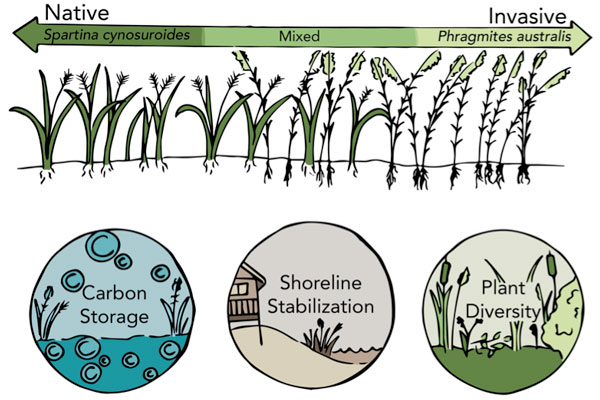

Image above: Seth Theuerkauf assessed three marsh ecosystem services — carbon storage, shoreline stabilization and plant diversity — in areas with varying abundance of the invasive marsh grass Phragmites australis. Image by Elise Gilchrist/N.C. Coastal Reserve

In summer 2014, Brandon Puckett and I grew curious about Phragmites australis, an invasive marsh grass that has become increasingly common throughout North Carolina’s marshes. The invader displaces native marsh vegetation, such as big cordgrass, Spartina cynosuroides. In addition, efforts to eradicate Phragmites often require costly, broad-scale application of herbicides or fire over many years.

Previous studies have documented that Phragmites can harm plant diversity and habitat for threatened and endangered bird species. But Puckett, then a postdoctoral researcher at NC State’s Center for Marine Sciences and Technology (CMAST), and I wondered how Phragmites might affect other ecosystem services that we value from our marshes — such as the ability to store carbon or stabilize eroding shorelines.

We also wanted to know if the quantity or quality of these ecosystem services would vary depending on how prevalent Phragmites was within the marshes. Furthermore, how might the answers to these research questions affect Phragmites management efforts in North Carolina?

Flash forward to 2015, when I received the North Carolina Sea Grant and N.C. Coastal Reserve Coastal Research Fellowship, providing a unique opportunity to seek out the answers to these questions. My fellowship research was conducted within Kitty Hawk Woods and Currituck Banks Reserves, two marsh ecosystems in the northeastern part of the state.

To measure Phragmites’ effect on shoreline stabilization, we installed pairs of markers and measured the position of the marsh edge relative to the benchmark measurements taken in 2015 and 2016. Photo by Seth Theuerkauf.

I was able to continue working with Puckett, by then the research coordinator for the N.C. Coastal Reserve, on the project. Our team also included scientists and partners from CMAST, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Institute of Marine Sciences and the reserve.

Donning our snake chaps to deter possible cottonmouth bites, Puckett, Scott Crocker (then with the reserve), Kathrynlynn Theuerkauf (a graduate student at CMAST and my wife) and I first took to the marshes in Kitty Hawk Woods and Currituck Banks in April 2015.

Scott helped us identify field sites with varying amounts of Phragmites — from areas with only native grasses, to those with a mix of grasses and to those with only Phragmites. We used those field sites to determine how increasing prevalence of Phragmites affected the ability of marshes to stabilize shorelines, store carbon and maintain plant diversity.

We returned to the marshes later that summer to install shoreline-erosion markers — metal stakes installed waterward and landward of the marsh — that allowed us to take precise measurements of each marsh’s shoreline edge. By comparing the measurements taken in 2015 and 2016, we were able to assess whether marsh was accreting (growing) or retreating (eroding). We also could see how that varied depending on the abundance of Phragmites.

To measure carbon storage, we extracted sediment cores from marshes (left) and measured the amount of carbon stored within the sediments (right). Photos by Brandon Puckett/N.C. Coastal Reserve.

We also collected samples of marsh sediment at our field sites to determine if increasing abundance of Phragmites affected the ability of marshes to trap and store carbon. Back in the lab, my brother Ethan Theuerkauf, then a doctoral candidate at IMS and now with the Illinois State Geological Survey, helped us process the samples to determine how much carbon was stored within the sediments.

We also assessed plant diversity, an important indicator of ecosystem health. Our team revisited the research sites to determine the variety of plants that were present and how abundant they were. Despite the dense canopy of the marsh, we identified over 40 unique plant species within the understory vegetation of the marsh. I was amazed by the hidden diversity of plants we observed!

In summer 2016, we wrapped up the final field sampling for the project, and I began digging into the data analysis with my advisor, David Eggleston of NC State. After analyzing all of the data, we found that the increasing abundance of Phragmites within the reserves did not appear to reduce the ability of marshes to stabilize shorelines, store carbon or maintain plant diversity.

Our results were surprising given that earlier research had found that Phragmites had a negative effect on marsh ecosystem services. However, many of those previous studies examined wetlands that have had human interventions, such as shoreline development or construction of drainage canals. Our study, however, was conducted in undisturbed marsh habitat within a protected reserve system.

Our findings highlight the importance of maintaining protected reserves. These areas may provide a strong defense against invasive species and could reduce the time and resources needed to eradicate these species. Furthermore, our study highlights the importance of determining whether invasive species actually harm the ecosystem services provided by our marshes when considering management options.

Our research on the effects of Phragmites australis on marsh ecosystem services was recently published in PLOS ONE at journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0173007.

Seth Theuerkauf is a doctoral candidate in biological oceanography at North Carolina State University’s Center for Marine Sciences and Technology. He was the 2015 coastal research fellow.