There is value in establishing a connection between nature and children. As children learn and grow, they will take the lessons of their childhood into adulthood, applying the values they absorbed to their higher education, careers and personal lives.

Zhenzhen Zhang, a third-year forestry and environmental resources Ph.D. student in the College of Natural Resources at NC State University, understands this on an academic as well as a personal level. She has applied her joint North Carolina Sea Grant – NC WRRI graduate research fellowship to aid her goal of removing social barriers to sustainability challenges.

Zhang has brought her work to public elementary schools in Wake County and has pieced together a picture of how students and teachers perceive and interact with green infrastructures (GI) in their schoolyards.

Zhang seeks to understand the social impact of existing GI at public elementary schools and highlight how green schoolyards can be used as an educational tool for teachers, ultimately acclimating children to current and future sustainability issues.

One of the prominent sustainability challenges our state and places throughout the world face today is stormwater runoff threatening urban water systems. As a promising mitigation tool, GI provides ecosystem services such as improving water quality and reducing the urban heat island effect.

However, the prominence of GI is limited by the political complexities resulting from adding these structures, as well as a lack of finances and incentives. Therefore, Zhang aims to overcome these barriers by integrating GI into public school systems and promoting their importance, to encourage more effective systems for widespread GI implementation.

“We can provide the groundwork to benefit the water system.”

– Zhenzhen Zhang

As locations with a large proportion of impervious surfaces, the adoption of GI in schoolyards can not only alleviate runoff and provide valuable ecosystem services, but also can introduce GI to broader communities. Additionally, these accessible green spaces have the potential to benefit students’ physical and mental health by promoting outdoor activities and connecting students with nature.

In her two-part study, Zhang first used remote sensing to classify the land cover at Wake County public elementary schools. She would then visit school grounds in person to note any existing GI and analyze it.

For the second part of her study, Zhang conducted a survey for teachers and students, to understand their interest and perception about the GI already present at their schoolyards. Through the survey, Zhang developed a clearer picture of what teachers and students think of their school yards and the actual potential for green structures to benefit learning and teaching.

Born in Chongqing, China, Zhang received her undergraduate degree in ornamental horticulture from Beijing Forestry University in China. As she worked toward her degree, she developed a strong connection with nature and the plants, trees and flowers she studied, inspiring a passion for sustainability.

In 2014, Zhang moved to America to continue her studies and received a master’s degree in landscape architecture and environmental science from the University of Michigan. Through her studies, she gained three years of experience working with GIs, expanded her knowledge on ecological design, and developed an ambition to study GI’s potential to promote a sustainable future.

Thus, Zhang is pursuing a Ph.D. at NC State University, applying her knowledge in green structures and ecological designs to her work in the broader realm of climate change.

“I was interested in climate change and how it challenges urban systems pretty seriously,” Zhang says. “So that’s something that I would like to continue to work on: using GI as an adaptation tool for climate change and understanding the benefits.”

As someone who established a valuable connection with nature in her higher education studies, Zhang hopes to generate a similar connection between younger students and nature, so they may understand climate change issues and other sustainable challenges faced today and in the future.

Using her joint North Carolina Sea Grant – WRRI fellowship award to cover transportation costs, Zhang visited over 40 elementary schools in the Wake County public school system, recording an inventory of the kinds of green structures on each elementary school’s grounds.

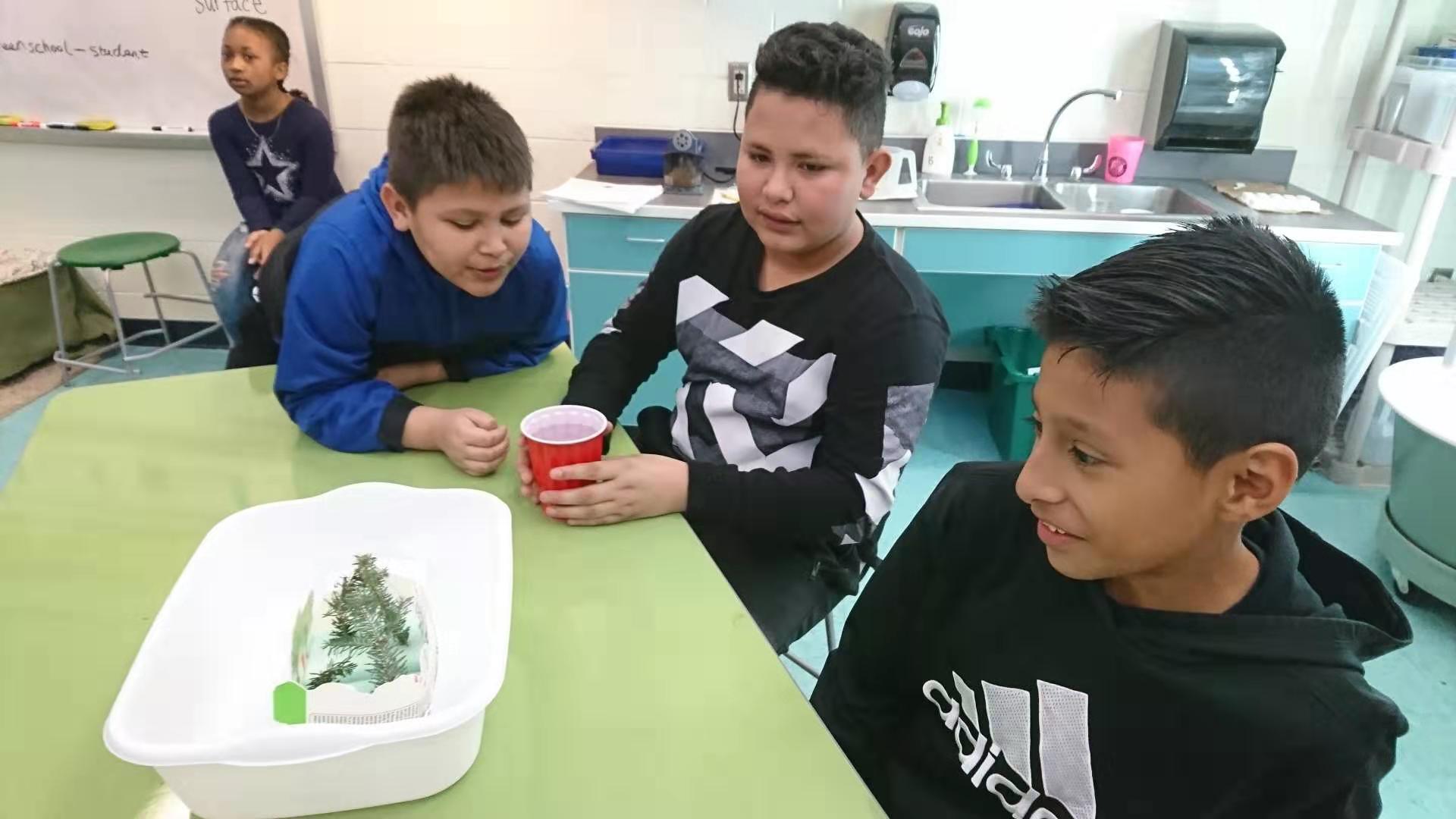

Zhang instructs her students to build models demonstrating the benefits of green structures and the concept of permeable and impermeable surfaces.

From this survey work, Zhang found that three to four of the elementary schools have rain gardens, 17 elementary schools have an edible garden, 29 elementary schools have a flower garden and 32 elementary schools have woodlands, which are inaccessible to students due to the potential dangers within them. Additionally, Zhang only found six schools with retention ponds – a GI designed to capture stormwater runoff – despite the fact that, her findings show, impervious surfaces occupy an average of 38% of the schools’ grounds.

Zhang then worked with public elementary school teachers, compensating them for their participation with funds from her award.

“I will prepare questionnaires for students and teachers about what kind of GI they think are important and the benefits they view from their schoolyard,” Zhang explains.

Despite the monetary compensation, one of Zhang’s most prominent challenges has been garnering teacher participation. While she sends over 1,000 emails to fourth- and fifth-grade teachers, only a few respond, since many teachers are already busy with their job’s workload.

However, teachers that do participate hand out Zhang’s surveys to their students, helping her understand the full scope of how students interact with the GI available to them.

Based on the survey results, Zhang finds that the lowest frequency activities listed on her surveys include exploring the woods, looking at animals or insects and spending time in gardens, revealing that activities relating to nature are not popular activities among these students.

To garner a curiosity and appreciation for nature on school grounds, Zhang interacts with fourth- and fifth-grade students through crafts and models that help them envision the benefits of GI.

“We use runoff models that let kids compare the volume of runoff coming from surfaces with different land cover,” Zhang says. “The kids really like those models because [they’re] really engaging. It’s a really unique experience that I got from this research.”

Using simple models with milk bottles, sponges and impervious objects, Zhang demonstrates concepts of impervious surfaces and water infiltration, explaining how green spaces will aid and protect water quality.

Unlike her colleagues, Zhang does not have an extensive background in education and working with children.

“My background is from environmental science. I worked more with plants than people, so it’s a pretty unique situation,” Zhang admits. “It’s my first chance to do surveys and interact with so many people.”

Thanks to these new experiences, Zhang has been learning and adapting quickly throughout her research work and deeply enjoys what she does, especially engaging with fourth and fifth graders personally.

Zhang’s students study the effectiveness of green structures with hands-on models.

Zhang plans to continue her research with an aim to have GI integrated into public school systems, due to their potential to improve outdoor education for kids and teachers. She hopes her work will be able to break down social barriers to mitigating climate change and solving sustainable challenges.

Currently, Zhang has finished analyzing the survey results and, thus, is preparing multiple manuscripts for different journals, to start sharing her findings to different audiences.

In the future, Zhang will continue using her fellowship to support her travels to conferences, such as the American Geophysical Union annual meeting and the International Conference on Urban Ecological Design.

As Zhang communicates her work to different audiences, she aims to encourage the integration of GI in public systems beyond public schoolyards.

“I would like to provide the pathways to expand the green schoolyards within the municipalities,” Zhang explains. “We can provide the groundwork to benefit the water system.”

From a blog post published on WRRI’s website.

##