BY AARON RAMUS

Aaron Ramus (above) received the 2020 Coastal Research Fellowship, which North Carolina Sea Grant and the N.C. Coastal Reserve and National Estuarine Research Reserve Program sponsor jointly. Ramus, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of North Carolina Wilmington, studies the ecological impacts of “Gracilaria” in estuaries in the Southeast. He received his master’s in marine biolog y from UNC Wilmington and his bachelor’s in biology from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

from the Autumn 2021 issue of Coastwatch

Intertidal mudflats, shallow muddy areas exposed during low tide, are actually quite common in North Carolina’s estuaries. Although they might not seem as scenic or picturesque as other coastal habitats, these mudflats are home to myriad invertebrates — species without a backbone — as well as to fish and seabird populations.

These mudflats also support numerous fisheries, including the hard clam Mercenaria mercenaria. Hard clams are edible, filter-feeding bivalves that constitute the basis for a popular recreational and major commercial shellfishery in North Carolina that generates more than $3.7 million annually, according to the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries.

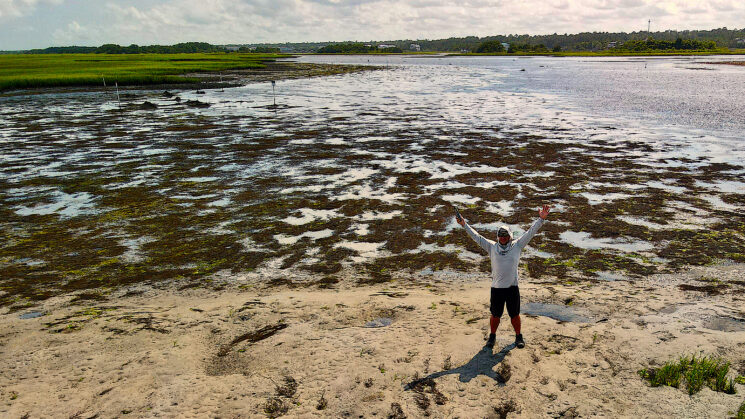

Does the presence of Gracilaria affect the production of hard clams, like these on the Masonboro Sound? Credit: Aaron Ramus.

However, many of North Carolina’s mudflats are now also home to a new species — a black, stringy, disheveled-looking seaweed known as Gracilaria vermiculophylla. In fact, nonnative Gracilaria has recently invaded almost every estuary in the southeastern United States, from Georgia to Maryland, and it appears Gracilaria is here to stay.

When Gracilaria invades, it forms complex micro-habitats in these intertidal areas that previously were largely devoid of vegetated structure. Because predators — such as whelks, seabirds, stingrays, and blue crabs — play a major role in controlling populations of benthic (bottom-dwelling) invertebrates on intertidal mudflats, Gracilaria could provide benthic prey with a refuge from predators. This could potentially modify predator-prey interactions on invaded mudflats, with important implications for the production of hard clams in North Carolina estuaries.

Many invasive species have negative impacts on the functioning and health of ecosystems and pose serious challenges for managers. In particular, it’s often unclear exactly where invasive species occur, and, even when we do know, we frequently don’t understand the invader’s impacts adequately.

For my Coastal Research Fellowship, I sought to address these challenges in two ways. First, I conducted surveys to enhance our understanding of Gracilaria’s distribution and abundance (and, thus, its potential impacts) along the N.C. coast. I searched the “waterbearing” N.C. Coastal and National Estuarine Research Reserves for Gracilaria and, when I located it, recorded its abundance. My survey detected the presence of invasive Gracilaria in five reserves and revealed that Gracilaria covered more than 10% of intertidal mudflats in four of the reserves — all of which are along the central and southern portion of the state’s coast. Ultimately, I developed a web-based interactive map of Gracilaria’s distribution and abundance to assist managers in their endeavors.

Second, I examined the indirect effects of Gracilaria on predator-prey interactions and on other aspects of the benthic community, including the production of hard clams, by conducting an experiment on intertidal mudflats in the Masonboro Island National Estuarine Research Reserve. My experiment manipulated the presence of Gracilaria and predators simultaneously in experimental plots by either manually removing Gracilaria or using cages to exclude predators. After two months, I sampled the plots using sediment cores to collect smaller invertebrates and juvenile hard clams and by digging with a clam rake to recover adult hard clams.

Ramus manipulated the presence of Gracilaria and predators simultaneously by either manually removing Gracilaria or using cages like this one to exclude predators. Credit: Aaron Ramus.

The results showed:

• Gracilaria strongly and positively affects the overall abundance and diversity of the benthic community.

• Predator exclusion had a negligible effect on the benthic community. The natural mortality of juvenile hard clams (as well as other benthic invertebrates) is very high, independent of whether predators are excluded.

• Most importantly, neither predator exclusion nor the presence of Gracilaria significantly influenced the production of hard clams.

These findings suggest that Gracilaria’s overall impact on the ecosystem falls somewhere between positive and neutral. It would appear that invasive Gracilaria is neither “good” nor “bad” for this estuarine shellfishery and is simply a new feature of North Carolina’s mudflats. Consequently, taking management actions to eradicate this invasive seaweed might not be necessary to preserve the health of our state’s hard clam fishery.

View an interactive map of Gracilaria’s distribution and abundance.

Read more about the Coastal Research Fellowship.