Above: Chester Lynn, left, is an O’cocker, or Ocracoke native. Sociolinguist Walt Wolfram, right, began studying the island’s brogue 20 years ago.

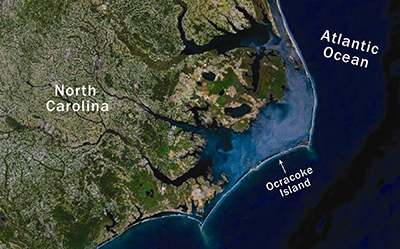

To sociolinguist Walt Wolfram, North Carolina is a “dialect heaven,” potentially offering more dialect variation than any other state. While the brogue spoken on Ocracoke Island may sound similar to other Outer Banks dialects, certain features are distinctive to the island. You can learn more about the history and evolution of Ocracoke’s brogue in this story from the Winter 2018 issue of Coastwatch.

Below is a brief guide to Ocracoke brogue vocabulary, grammar and pronunciation. For a deeper dive, check out Hoi Toide on the Outer Banks: The Story of the Ocracoke Brogue (UNC Press), by Wolfram and Natalie Schilling-Estes. For middle-school lesson plans developed by NC State faculty members Jeffrey Reaser and Walt Wolfram, visit Voices of North Carolina Dialect Awareness Curriculum.

VOCABULARY 101

VOCABULARY 101buck (n.): A good friend, usually male. A female friend may be a puck.

call the mail over (v. phrase): Distribute the mail.

dingbatter (n.): A nonnative of Ocracoke or the Outer Banks.

foreigner (n.): An off-islander.

meehonkey (n.): A game of hide-and-seek played by earlier generations of children on Ocracoke Island, or a call used while playing this game.

mommuck (v.): To harass or bother.

O’cocker (n.): A person born and raised on Ocracoke; a native as opposed to a nonnative resident.

Ocracoke (n.): The name of the island, probably derived originally from the Algonquian word waxihikami, meaning “enclosed place or fort.” Through misspelling and English-like pronunciation, the word became Wococon and, eventually, Ocracoke. In one popular island legend, Ocracoke comes from the phrase, “Oh, crow cock,” which was spoken by the infamous pirate Blackbeard as he waited to do battle at sunrise with the governor’s forces that had come to capture him.

quamished (adj.): Sick to the stomach.

slick cam (n.): A very calm water, typically used with reference to the sound waters, as in, “It was a slick cam out there today.” Cam is pronounced so that is rhymes with ram. Also slick calm.

water fire (n./v.): Light that appears on the surface of a body of swampy water at night, caused by gases released by decaying plant matter.

In this this video, O’cockers offer examples of how to use these vocab words.

A- prefixing: An a- prefix is sometimes attached to verbs that end in -ing. For O’cockers, this use is usually limited to emphasis when telling an animated story. Precise rules govern where the a- can be added. The word that follows must be a verb, as in, “He was a-chasin’ the cat.” The prefix also cannot follow preposition. For instance, an O‘cocker might say, “They make money a-fishing,” but not, “They make money from a-fishin.’” In addition, the a- must be used with a verb whose accent is on the first syllable, as in, “She was a-hollering at the dog,” but not, “She was a-discovering the cave.”

A- prefixing: An a- prefix is sometimes attached to verbs that end in -ing. For O’cockers, this use is usually limited to emphasis when telling an animated story. Precise rules govern where the a- can be added. The word that follows must be a verb, as in, “He was a-chasin’ the cat.” The prefix also cannot follow preposition. For instance, an O‘cocker might say, “They make money a-fishing,” but not, “They make money from a-fishin.’” In addition, the a- must be used with a verb whose accent is on the first syllable, as in, “She was a-hollering at the dog,” but not, “She was a-discovering the cave.”

To Be ~ Weren’t: For negative sentences in the past tense, the Ocracoke brogue uses weren’t for all subjects, as in, “The dog weren’t here.” For affirmative sentences in the past tense, was is used, as in, “The dog was.”

For O’cockers, this use of weren’t is part of island identity, distinctively used to set an islander apart from someone from the mainland. This feature is still used by some younger speakers.

Locative to: The preposition to is used on Ocracoke and the Outer Banks where other dialects use at or on, as in “She’s to the dock” in response to the question, “Where is Rena Del?”

The pronunciation of the i vowel: This is probably one of the most noticeable and iconic pronunciation features. In early modern English, the i vowel sounded like uh-ee (“high tide” = h-uh-ee t-uh-ee-d). Ocracoke English keeps this pronunciation; however, the modern pronunciation of time sounds more like toim, and side more like soid. The oy sound can become more pronounced when O’cockers perform their dialect for tourists. For an example, listen to brogue performer Rex O’Neal.

The ai for ou: The vowels in words like sound and brown may come across like saind and brain, respectively, and there are cases where outsiders have confused a brown pocketbook with a brain pocketbook. This pronunciation is unique to the islands of the Outer Banks and Chesapeake Bay in the United States.

The pronunciation of ar for ire: An i vowel followed by r sounds like ar, as in far for fire, or tar for tire. This feature is shared by a number of Southern-based varieties of English. Listen to the clip below for an example. Also watch this video, in which an O’Cocker shares an anecdote about miscommunication arising from this pronunciation.