Every summer, many people flock to North Carolina’s Outer Banks as a popular vacation spot to beat the heat. This year, visitors to Cape Point on Hatteras Island found a newly formed island — one that has captured nationwide attention.

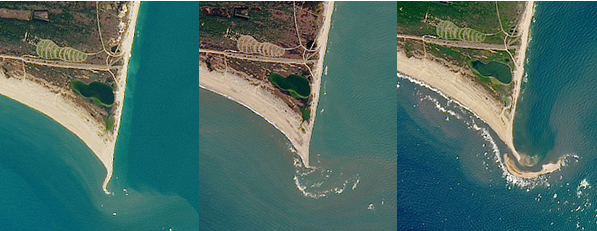

Images taken by NASA show the extended sandbar — dubbed Shelly Island by one of its first guests — became a subaerial, or above water, island in less than a year.

Images taken, from left, on Nov. 11, 2016, Jan. 28, 2017, and July 7, 2017, show the formation of Shelly Island.

Although the appearance may strike some folks as a mystery, Stan Riggs, coastal geologist from East Carolina University who has studied the Outer Banks extensively, knows to expect the unexpected when it comes to coastal North Carolina.

“Barrier islands are complex, and respond to oceanographic and atmospheric conditions. They are constantly changing. We currently can’t predict the weather very far into the future, so it is equally difficult to predict how the coastline will change in response to the weather into the future,” Riggs explains.

Riggs is not surprised that an island has appeared. The mystery lies not in that the island formed, but rather in the dynamics that caused the island formation, he notes. Particularly at Cape Point, weather patterns and currents contribute to a volatile and changing coast.

The Outer Banks have a unique geology and past, Riggs explains in his book The Battle for North Carolina’s Coast. Barrier islands are ribbons of sand separated from the mainland by an estuary.

Cape shoals — like Diamond Shoals off Cape Hatteras — are submarine sand piles, located in the ocean off each of North Carolina’s three capes. Perpendicular to the shore, the shallow shoals are largely responsible for the North Carolina coast garnering the nickname “The Graveyard of the Atlantic.”

Mariners often would not see the underwater shoals, thus running aground and ultimately sinking many ships. The Diamond Shoals extend seaward for about 10 miles directly off of Cape Hatteras.

Why these shoals are on the North Carolina coast and how they formed is still a big question for researchers. “We don’t have a clue how the currents and waves interact with the Diamond Shoals,” Riggs notes.

Residents and visitors to all of North Carolina’s coast know that with each storm, barrier islands change.

In 2003, an extreme example of change occurred with Hurricane Isabel. When the storm hit the coast, it created a new inlet between Hatteras and Frisco. This destroyed a portion of N.C. Highway 12 and left a stretch of water 2,000 feet wide. The inlet was filled and the highway repaired in the months following the storm.

Images taken from (top) Aug. 25, 2003, and Nov. 13, 2003, show the changes that a storm like Hurricane Isabel can bring to the coast.

Storms cause change, but lack of storms also brings change. In the past eight to 10 months, weather conditions have been ideal for accretion, or the build up of sediment, Riggs notes.

“If you look at the storms since last October, we had three tropical storms that impacted the coast. Since then, our weather has been very mild with all nor’easters developing north of us. We have generally been under high pressure with southwesterly winds since last October. Those weather conditions over a long period of time are building conditions at the cape. A submarine shoal is almost always offshore. Enough sand has accumulated on the shoal for it to become subaerial. We haven’t had the storms to prevent the shoal from accreting sand, so they just kept building,” he explains during a chat prior to Hurricane Gert rolling offshore.

Due to this constant high-pressure system and southwest wind pattern, it is likely that sand has been transported from the south shore of Buxton Woods and is being deposited about 50 yards off of Cape Point, he adds.

The new mile-long island is about a football field wide, and has grown since May. “I think the island is in the process of welding to the beach. Cape Point is very long right now and in a constructional phase. Ultimately, barring any nor’easters, the island may weld itself to the south shores of the beach,” Riggs suggests.

This is not a unique phenomenon. Similar processes built all of the beach ridges that make up the Buxton Woods section of Hatteras Island over the past 1,700 years, he adds.

Spencer Rogers, North Carolina Sea Grant coastal construction and erosion specialist, notes that this isn’t the first time accelerated changes have occurred on Cape Hatteras.

“Before Hurricane Isabel in 2003, Cape Point was eroding and reached a point 3,500 feet north of its present location. After Isabel, Cape Point grew south 2,900 feet. It did this at a rate of 6 feet per day, which is an incredible rate.”

Islands often appear and disappear off the coast. Rogers smiles as he asks, “Did anyone notice that an island formed off of Cape Point in 2009? Or when one formed off Cape Lookout before 2010?”

The coast responds to changing energy during storms and seasons. Calmer waters in the summer bring long, wide beaches, while more frequent tumultuous waves in the fall and winter bring ideal conditions for surfing, but smaller beaches, Rogers adds.

Satellite images identify the growth of the new island, but the exact processes or movement of sand responsible for its formation were not documented. “Nobody was monitoring this site,” Riggs adds.

Both scientists suggest more research would help understand the detailed weather conditions and processes that shape the Outer Banks. More frequent aerial photography, weather tracking and studies of the currents and natural phenomena all could be helpful.

Much work remains to be done before we fully understand our Outer Banks, they note. But Riggs and Rogers, along with other scientists, residents and visitors can agree: The coast is always changing.

For more information about safety concerns, read Pack Safety to Visit Shelly Island. To see how the North Carolina coast has continued to change since 1984, try North Carolina Sea Grant’s Shifting Shoreline: Inlet Atlas time machine. Special thanks to the NASA Landsat team.