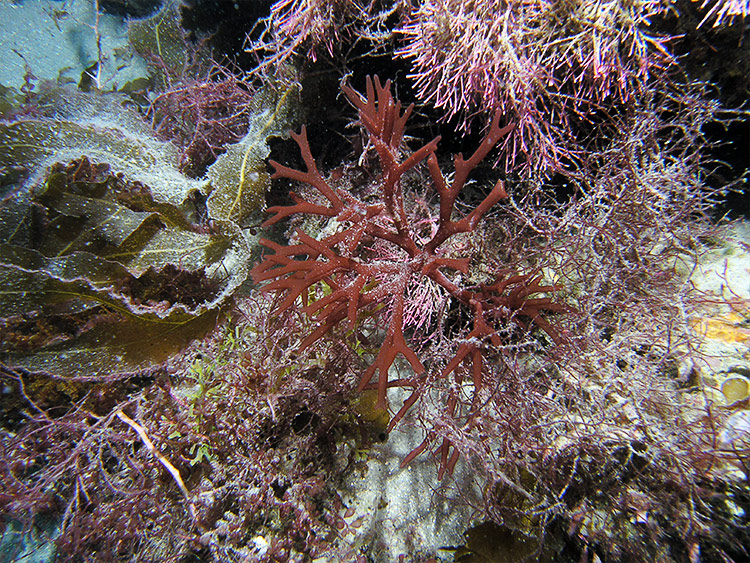

The ocean ran red around Bodie Island last October. Local reports said that the discolored water stretched from Oregon Inlet toward Buxton.

Fearing a harmful algal bloom, the N.C. Aquarium on Roanoke Island postponed its release of Barnacle, a rehabilitated loggerhead sea turtle. They planned to wait until the bloom cleared or was identified as not harmful.

Scientists from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science called in area experts to help.

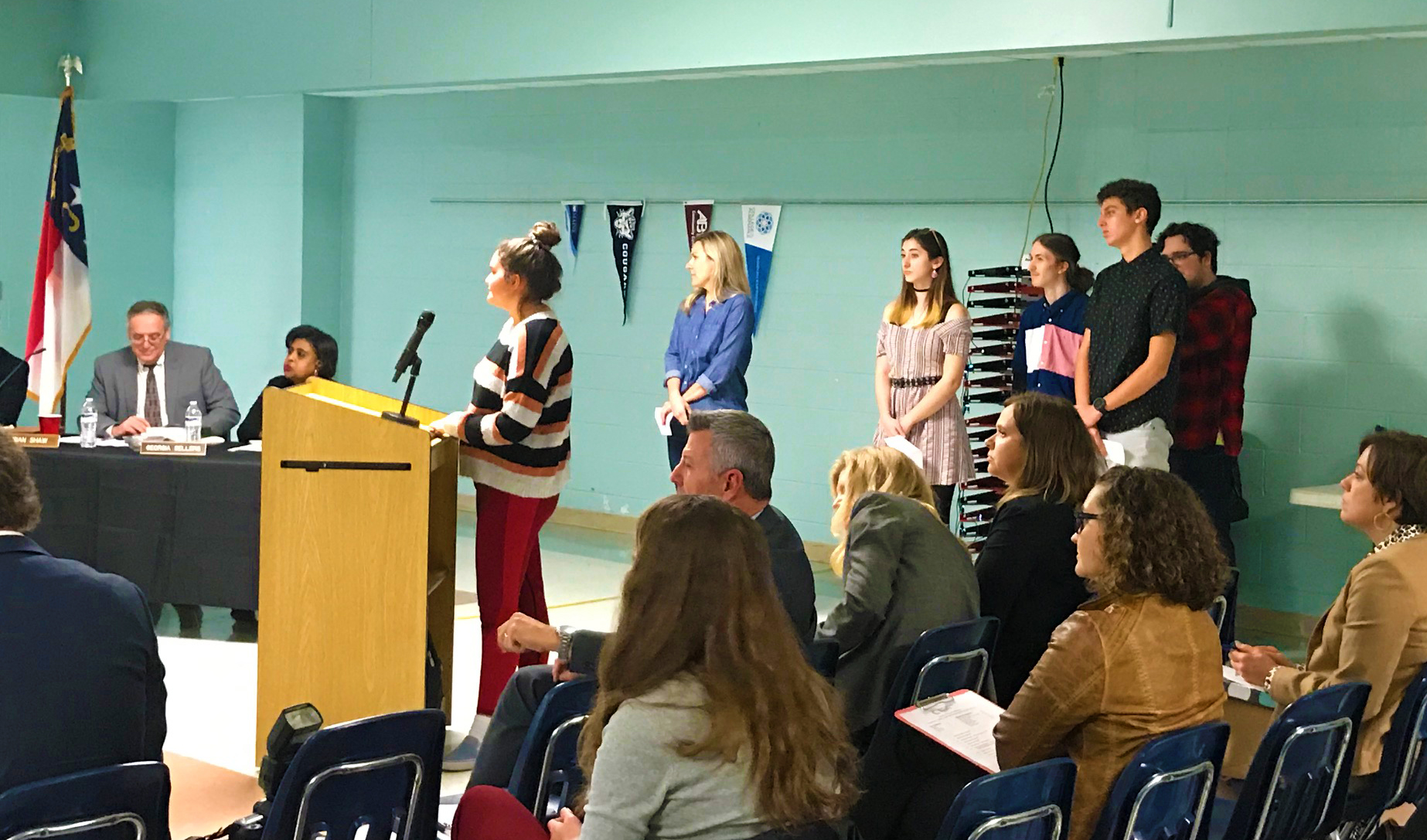

That request went to First Flight High School in Kill Devil Hills. In response, students waded in, literally and figuratively. They collected water samples, attempted to isolate what was changing the water’s color and sent their analysis to NOAA.

With the students’ help, NOAA scientists determined that the October red tide event was caused by a bloom of Mesodinium rubrum, an organism that typically is nontoxic to humans and marine life. Barnacle was released a few days later.

Andrew Kiousis, a high-school senior, and Advanced Placement science teacher Katie Neller recall that event. Science, they imply, is not for the faint hearted — or, in this case, for those who are averse to adverse weather.

“It was cold,” Neller remembers. “A scientist has got to do what a scientist has got to do.”

Kiousis is part of the Phytoplankton Research Team — commonly called Phytofinders — that Neller directs and advises. Founded in 2005, this group has helped detect and confirm algal blooms along the Outer Banks for the past decade. The team is part of NOAA’s Phytoplankton Monitoring Network, or PMN.

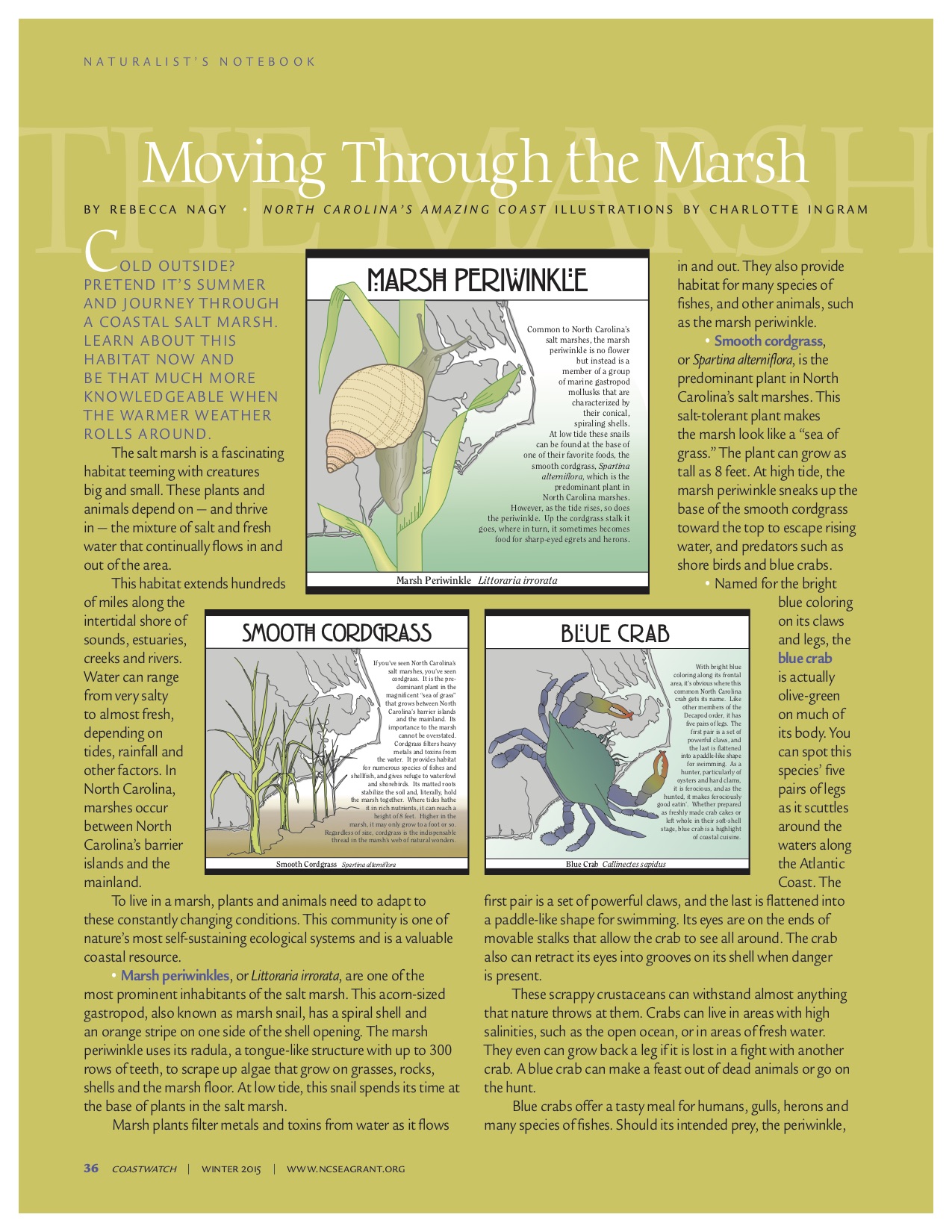

“The network uses citizen volunteers to monitor marine phytoplankton in coastal waters, with special attention to species that cause harmful algal blooms that can cause human health problems,” explains Terri Kirby Hathaway, North Carolina Sea Grant marine education specialist.

Sea Grant has been involved with Phytofinders since its inception, through Hathaway’s work with the Centers for Ocean Sciences Education Excellence SouthEast.

“In 2005, Sea Grant hosted and assisted with three workshops — in Manteo, Beaufort and Wilmington — to introduce the SouthEast Phytoplankton Monitoring Network to North Carolina teachers,” Hathaway adds. “In the beginning, North Carolina had roughly 10 sampling sites.”

Phytofinders was one of the groups that emerged from those meetings.

“They were our first group in North Carolina,” says Steve Morton, who leads PMN. “They’ve been the most consistent.” He notes that there currently are seven groups in the state, joining a nationwide volunteer effort that samples at 190 sites.

Phytofinders quickly made contributions to the monitoring work. Within a year — in late 2006 — the students identified the sources of a harmful algal bloom in North Carolina.

“They were actually the very first group to find this toxic diatom called Pseudonitzschia in the southeast,” Morton recalls. That was the farthest north this organism had been identified in the Atlantic Ocean.

This identification of Pseudo-nitzschia helped scientists determine the cause of death when some marine mammals washed up around the same time and location.

“We would not have tested them for domoic acid if the group didn’t see it in the water first,” he explains.

Domoic acid, produced by Pseudonitzschia species, accumulates harmlessly in fish and shellfish. However, the toxin can cause brain damage, or even death, in mammals, including marine mammals. The Phytofinders’ analysis changed how researchers analyzed the dead animals.

The team also maintains a lot of information — about a decade’s worth of continuous monitoring data from the Outer Banks. All their data are available at products.coastalscience.noaa.gov/pmn/.

Neller, a veteran science teacher, started Phytofinders to get her students more involved in what they learned in class. She wanted to take science beyond the walls of her lab. “I began to think students weren’t curious or interested,” she says.

Very soon, she found her students linking what they saw at the piers with their lessons.

“The work connects science to them even when they are sitting at a desk with a textbook,” Neller says. “Dissolved oxygen, climate change — every time I can bring in phytoplankton, I do. Kids can identify with what they’re learning in their books because they’ve seen the connection with the real world.”

That was true for former student Katlin Allsbrook. “In the classroom we learned about scientific techniques and discoveries, but we didn’t always get to see them in action. The Phytofinders allowed me to have real-life experiences of collecting data in the field and then analyzing it,” she recalls. “I think all of the information that I had learned about in my science classes really clicked and was more meaningful to me when we discovered the bloom.”

DEDICATED AND DECORATED

The Phytofinders meet twice a week. After school on Mondays, they divide into two teams to sample the water at Jennette’s Pier in Nags Head and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Field Research Facility at Duck. The next day, the high schoolers return to Neller’s lab during their morning free period to examine the samples collected the day before.

Attendance fluctuates — some come on one day, some show up for both days — but Neller is grateful. “I’ll take them whenever I can get them,” she says. “It is strictly student run. I want them to decide.”

She is adamant that Phytofinders be a fun and interesting activity, not another pressure or stress for her students. So she encourages collaboration, not competition, while conducting scientific research.

However, Neller has to contend with other school activities for students. And every year, her seniors graduate and move on.

“One hundred percent of Phytofinders go to college,” she notes proudly. Her students mostly end up in the science and engineering fields.

“It is an excellent program,” acknowledges Matt Thibodeau, a senior who plans to study material science in college.

“Being a part of the Phytofinders team confirmed that a science-related field was what I wanted to do,” Allsbrook says. “The experience allowed me to develop and refine basic science skills that were crucial to my undergraduate and graduate science courses, and also my current career.” She recently earned her master’s degree in medical genomics from the University of Cincinnati.

The Phytofinders’ work is the gateway to many opportunities for the students. Kiousis, who wants to major in genomics in college, worked on a phytoplankton exhibit during his internship at Jennette’s Pier, which is part of the N.C. Aquariums.

Some Phytofinders have presented peer-reviewed papers at an academic conference.

Beyond the classroom, Neller hopes that their efforts will benefit the surrounding Outer Banks community that has strong ties to the ocean for jobs and recreation.

“A toxic event would be devastating to major fisheries and the economy,” she says. “We want to find ways to predict when those things will happen.”

State officials, local communities and organizations have recognized Phytofinders’ contributions.

Their efforts in identifying the first Pseudo-nitzschia bloom in the state earned the team the N.C. Governor’s Conservation Achievement Award for youth conservationists in 2007. The awards are the highest natural resource honors in the state, presented annually by the N.C. Wildlife Federation and the governor’s office.

In 2013, the team received the Albemarle Stewardship Development Program Significant Achievement Award from the Albemarle Resource Conservation and Development Council. They were honored for their commitment to environmental education and stewardship.

Since 2009, the Phytofinders team has received annual financial support from the Oceanic Engineering Society of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, also known as OES IEEE.

“This is a huge return on investment and bang for your buck,” says Todd Morrison, OES member and ocean engineer. “If we give a $5,000 scholarship to one grad student, that helps one person. But $5,000 per year here, suddenly instead of five kids, it is 50 kids who are involved in the program, who are getting something out of it. And some of them end up being published authors.”

The first round of funding came with a requirement that the students write and present academic papers at OCEANS 2012, the society’s annual meeting. OES extended the funding for another three years, with the same condition. Morrison is looking forward to seeing what the team will produce for OCEANS 2015 this autumn.

“A program of this quality is unusual in a high school. It’s more the kind of thing you’d see among undergraduate or graduate students,” he explains.

“We have been no end impressed,” he adds.

This summer, Jennette’s Pier will unveil a touchscreen display on phytoplankton that Kiousis helped develop during his internship. A companion panel will focus on the Phytofinders.

“We just wanted to highlight the high school for their contribution to science,” says Christin Brown, education programs coordinator at Jennette’s Pier.

In addition, she wants to introduce the facility’s visitors to PMN and its work via weekly citizen science programs — with involvement from the Phytofinders.

“I would like for one of them to actually lead it instead of one of our staff, because they are so knowledgeable, and it would be a unique opportunity for them to do some outreach,” Brown says.

Echoing Morton and Morrison, Brown notes that Neller’s enthusiasm and dedication enable Phytofinders to excel, in spite of student turnover.

“The composition of the Phytofinders changes annually, with seniors graduating and underclassmen joining or taking on leadership roles in the group. But what remains constant is the students’ dedication to their job as citizen scientists and the support and mentoring they receive from Katie Neller,” Sea Grant’s Hathaway says.

“Teachers and students like these give me hope for our future.”

**********************************************************************************************

GET INVOLVED

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Phytoplankton Monitoring Network, or PMN, is an effort that engages citizen scientists — school groups, nongovernmental organizations and volunteers — to monitor sites for harmful algal blooms.

Volunteers sometimes are sent to ground truth local reports or satellite detection of potential bloom events. To sign up or learn more, go to products.coastalscience.noaa.gov/pmn/.

Residents of, or visitors to, the Outer Banks can help with phytoplankton monitoring projects at N.C. Aquarium’s Jennette’s Pier this summer. Contact Christin Brown at 252-255-1501 for more information.

This article was published in the Summer 2015 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: