SEA SCIENCE: A Fishery for All Seasons

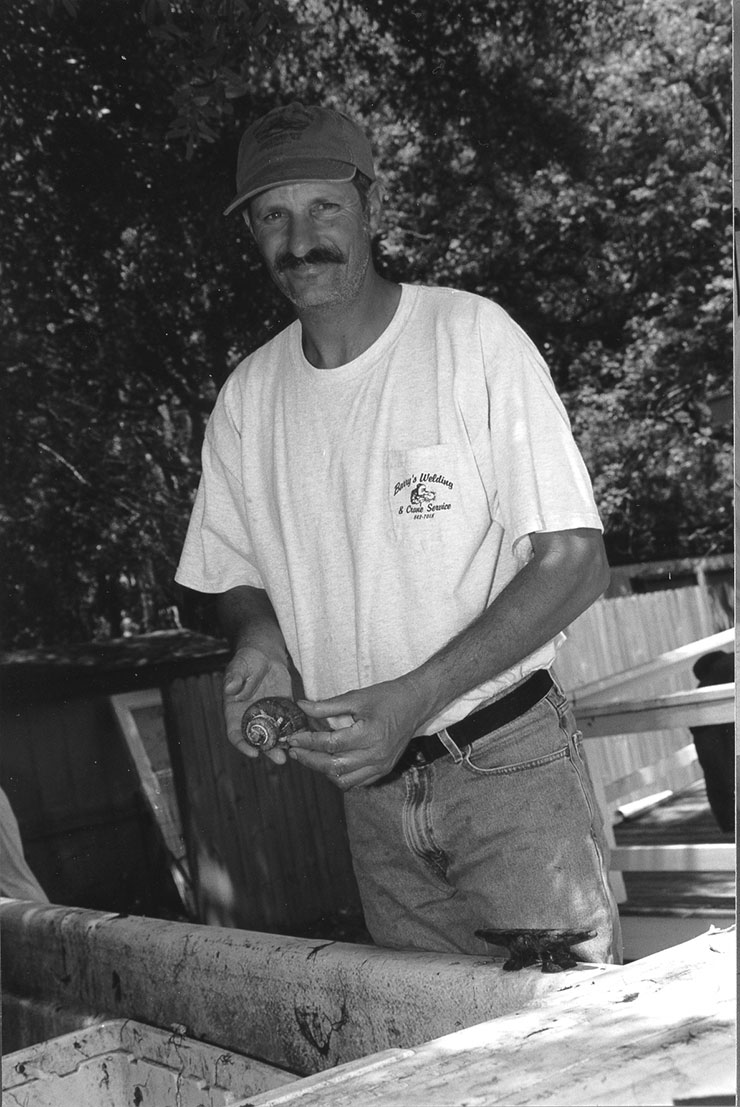

“You can have your conch and eat it too,” says Dave Beresoff, a Brunswick County commercial fisher.

That’s one conclusion he drew from a N.C. Fishery Resource Grant (FRG) project he completed with Elaine Logothetis, a marine biologist with the N.C. Aquarium at Fort Fisher.

The two set out to explore the feasibility of a viable conch fishery in southeast North Carolina. Could conch become an alternative target fishery during the months other traditional fisheries are less active?

From October 2002 through March 2003, they caught conch — and a few other surprises.

“I’m convinced that I can make a day’s pay setting conch pots in winter,” Beresoff happily reports.

Conch has become a general term used to describe various large, spiral-shelled gastropods. The whelk, a close cousin, is the predominant edible mollusk in North Carolina waters.

During the study, the researchers captured a total of 13,876 conch — about 45 percent of their overall catch. The predominant species caught was channeled whelk (Busycotypus canaliculatus), with some knobbed whelk (Busycon carica).

For their FRG study, Beresoff and Logothetis used both wooden lathe conch pots and wire crab pots to compare effectiveness. They placed the pots offshore, behind the breaking surf, at ocean depths from 15 to 30 feet.

Beresoff and Logothetis were more successful with wire crab pots than with traditional wooden conch pots; they caught the most conch in February and March; and they caught the largest individual animals in the fall.

They used a variety of “opportunistic bait,” that is, whatever was readily available — from menhaden to rays, fish heads and dead crabs.

“The more pungent the bait, the better,” Logothetis reports. Whelk, a predator, uses its well-trained nose, or proboscis, to seek out smelly prey.

Tom Likos, a local crabber, was on board as “baitmaster,” Logothetis says. He helped keep track of the type of bait that was used, the type of trap, and each location. He also pinpointed areas where he historically caught whelk in his crab pots during the winter months.

The bait issue is also important, because the literature indicates that horseshoe crab is the preferred conch bait. But, with declining horseshoe crab populations, the research team was happy to demonstrate the effectiveness of alternative baits.

CATCHING A BREAK

The bycatch is even more interesting.

“When we began the project, we worried that bycatch might be a problem,” Beresoff recalls with amusement.

But, when the economic value of the bycatch — blue crab, stone crab and octopus — exceeds the target species, it’s an enviable problem, he concedes.

In fact, the dollar and weight of marketable bycatch landed surpassed that of conch in ever month except December, they report.

Landing blue crab in the ocean during winter months is a significant break, Beresoff says. Ocean waters remain open to blue crab year-round, according to the state’s Blue Crab Management Plan, even when inland waters close for a brief period during January.

“Marketing to the year-round blue crab trade — in addition to the healthy conch market — is a huge economic benefit,” Logothetis adds.

And, documenting the presence of blue crab in ocean waters during winter months sheds light on the life history of the prized crustacean. Currently, the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries (DMF) is conducting a crab-tagging study of female blue crabs to determine staging areas, migration routes, timing and habitat of the female crab.

Since the conch study ended, Beresoff has caught a number of DMF-tagged crabs off-shore. “This says they do migrate into ocean waters,” he points out.

To help assess the off-shore population of blue crab, Logothetis and Beresoff will take the study a step further. They will tag females trapped off shore to learn if they return to inland waters — and if so, where they go. A grant from the Blue Crab Research Program will fund their continuing effort.

Their conch study also had another surprising finding. When they set trawl lines — 20 pots over 1,000-ft. of line — the pots stayed in place, even in heavy weather. This suggests that trawl pot lines could help solve the “ghost crab pot” problem.

Ghost pots are single crab pots that break loose from their buoys and potentially foul other fishing gear, stray into boating lanes, or become environmental trash.

SEA SCIENCE

Conchs and whelks are related as shelled gastropods, Logothetis explains.

Whelks are in the family Melongenidae, while true conchs are in the family Strombidae.

All whelks are carnivores and scavengers, and use their noses to find burrowing clams — or bait used in crab or lobster pots. They force apart bivalves with a strong foot and aperture lip. Or, they may chip away the shell of the prey until it is possible to insert its mouth and feed on the mollusk inside.

On the other hand, true conchs are herbivores that feed on algae. Their typical flared lip would prevent them from exhibiting carnivorous behavior.

The Queen Conch of tropical fame does not come as far north as North Carolina waters. They are protected in the Florida Keys and parts of the Caribbean due to over-harvesting. In some places, conch farms provide the sweet meet for commercial consumption — the main ingredient of stew and fritters.

Though whelks are not a protected species, many states do have commercial and recreational landing/harvesting restrictions.

Currently, North Carolina recreational anglers are limited to 10 per day per person, or not exceeding 20 per day per vessel. However, there are no commercial harvest restrictions for whelk, nor is there a fishery management plan in place. Should one be considered, though, further studies will be needed to document male/female distribution, growth rates and life history, Logothetis says.

FISHING BOAT SCIENCE

The conch study is not the first FRG project Beresoff has initiated. He previously has worked with scientists from the academic community to study fishing gear and red drum protection.

Beresoff provides project idea, field knowledge and equipment, while the scientists climb on board to collect samples or test gear and record data. Together, the strange boat fellows analyze and report findings that often prove of economic value to the fishing community.

The North Carolina General Assembly created the FRG program in 1994 to help protect and enhance the state’s fishery heritage. The Blue Crab Research Program was added in 2000 to focus exclusively on that fishery.

The idea behind the programs — funded by the General Assembly and administered by North Carolina Sea Grant — is to match traditional knowledge with research methodology to find workable ways to improve or protect limited marine resources.

Beresoff and Logothetis agree that the key to the success of these state-supported research programs is the marriage of academia and commercial fishing.

“There is no way a marine biologist can simulate what fishers know about the water, where the fish are, where to lower the nets or traps. The projects produce solid information that can be used in developing or revising fishery management plans,” Logothetis says.

The collaborative projects also enable fishers to become involved in decision making. “They understand the data because it comes from them,” she adds.

“In other words, scientists help document our truths,” Beresoff comments. “Programs such as the FRG help others view the reality of our business.”

Projects also are learning vehicles for participants.

“All the projects are different,” says Logothetis who also is doing the scientific work for an FRG shrimp study. “Each one provides an opportunity to grow as a scientist. There are things to learn out on the water that you can’t duplicate in a laboratory.”

In turn, Beresoff is acquiring a taste for scientific inquiry. “One thing leads to another. For every answer, there is another question to pursue,” he says.

THE PAYOFF

When Beresoff and Logothetis began the FRG conch project, they were focusing on boosting the year-round livelihoods of commercial fishers in North Carolina. New and alternative fisheries and markets are often sought to sustain commercial fishing families.

Conch pot fishing from Massachusetts to Virginia yielded $11 to $15 million in 1999, they say. In Georgia, the conch fishery is one of the most productive mollusk fisheries. And, South Carolina shrimpers fish for conch using trawls after the shrimp season.

In North Carolina, a small conch fishery is lucrative in Dare County during December and January.

Once conch was a profitable bycatch from flounder trawls in the southeastern counties. But, conch fishing disappeared in the region during the 1980s when flounder trawling ceased with the increase in flounder size limits.

Beresoff plans to continue polishing his conch fishing techniques — and the prospects for a sustainable fishery along the Brunswick County coast.

Logothetis believes there still is a profitable market for these edible snails that are known as “squngili” in Italian markets.

Conch may not provide a full-time fishery, but conch plus bycatch could add up to a profitable winter activity — having your conch and eating it too, as Beresoff puts it.

“All in all, it was a successful FRG experiment. The idea is to make money during the typically slow season, and we showed it could be done,” Beresoff concludes.

Channeled Whelk

Phylum: Mollusca

Class: Gastropod

Order: Neogastropoda (new snails)

Family: Melongenidae

Genus: Busycon

Species: canaliculatum

- This large univalve can grow to 8 inches. It is pear-shaped, with an elevated, conical spire and a broad body whorl that narrows into a long, slender, curved canal.

- Grayish to yellow-white in color, covered with a gray periostracum bearing minute hairs; its aperture is yellow.

- It is found on sandy bottoms, often traveling just below the surface, plowing through the sand with its strong, grey foot.

- Its range is from Cape Code, Mass. to northern Florida; was introduced into San Francisco Bay.

- Strings of egg capsules resemble small, oval change purses, each can hold up to100 eggs. Larvae exit a small hole at the top of each purse.

- Indians once used beads cut from the whorls around the axis of the shell as ornaments and money.

- These whelk are mostly are “right-handed,” or dextral, meaning the shell coils to the right. Hold the shell with the opening facing you. If the opening is on the right side of the shell, it is dextral.

This article was published in the High Season 2004 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: