The old barges sunk at the bottom of the Pasquotank River don’t look much like classic shipwrecks.

Blocky and rectangular, the abandoned hulks lack the distinctive curves of a schooner’s hull or the remains of intricate rigging that graced sailing ships. They didn’t carry much machinery or equipment and some are unceremoniously dubbed “dumb barges” because they had no propulsion and had to be towed.

But the chunky old vessels were once common along the Elizabeth City waterfront and as vital to commerce as the colorful riverboats, steamers and sailing vessels that ran up and down the Pasquotank River and Albemarle Sound.

“The barges are more like workhorses,” says Lindsay Smith, a graduate student in the Maritime Studies Program at East Carolina University in Greenville.

Smith is studying scores of watercraft intentionally discarded around Machelhe Island in the Pasquotank River, not far from the scenic Elizabeth City waterfront. She sees the dilapidated hulks, some dating to the early 20th century, as vestiges of the maritime traffic that flourished on area waterways before it moved to highways, railroads and air travel. Examining the vessels hidden in the dark water may also shed some lighten the economic and technological trends that shaped the region.

Smith’s research, supported by ECU and a grant from North Carolina Sea Grant, will document the abandoned vessels, as well as Elizabeth City’s development as a hub of maritime activity. Established in 1790, Elizabeth City’s water-based commerce grew with the completion of the Dismal Swamp Canal in the early 1800s and with the later expansion of shipping along the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway.

Of Waterfronts Past

The waterfront once bustled with wholesale grocery, tobacco and merchandise companies that shipped goods by water. At one time, ice and coal companies operated downtown as did an oyster house and shipyard. According to local historians, the Wright Brothers stocked up on provisions in Elizabeth City before heading to the beaches in northeastern North Carolina for their airplane experiments. From 1914 to 1940, the James Adams Floating Theatre, a showboat, docked in town while touring the area. In later years, oil companies and lumber mills kept the wharves busy.

Research by ECU and the state Division of Underwater Archaeology indicated at least 60 abandoned watercraft in what Smith calls the most extensive collection of abandoned vessels found so far in the state.

“It would be nice to find out if a single event caused it,” she says of the abandonment.

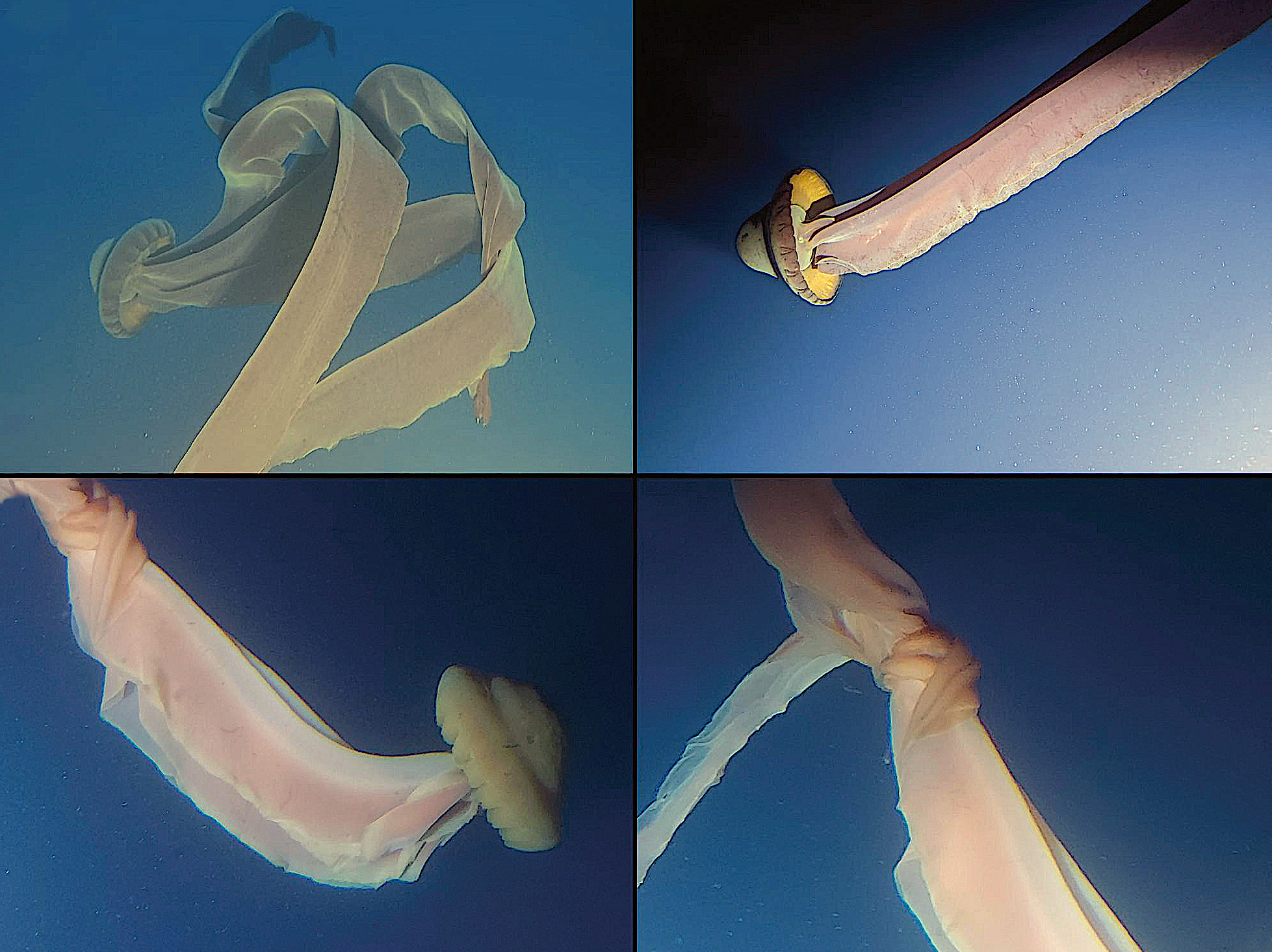

Since January, Smith and fellow graduate students have dived on several sites and recorded images of others with side scan sonar equipment that shows the profile of the river bottom. “From the surface, you can’t tell they are submerged,” Smith says of the wrecks.

Researchers are never sure what they will find. One promising site turned out to be a pile of discarded concrete. Local residents say there are also remains of an airplane or two that crashed in the river when the area was home to a Navy base in the 1940s. One crash site, located near the mouth of the river, used to be known as a good fishing spot. But that site is farther up the river from the boat graveyards that interest Smith and her colleagues.

At another site, sonar revealed the distinct outline of a schooner, the clean curves contrasting sharply with the rectangular shape of the barges. “There is one really beautiful schooner,” Smith says. “After looking at the barges…it’s interesting to see the nice curves.”

Plenty of Barges

The team found what’s left of a few schooners or steamers, but most are the remains of barges. These workhorses of the waterways once hauled lumber, coal, potatoes and other goods. After their working days, they were put out to pasture by being left to sink and rot away. Sometimes the barges were loaded with debris or sediment and intentionally sunk.

At one site, four abandoned barges — about 30 to 40 feet wide and 200 feet long — were apparently discarded together. Now they form a small island with trees growing out of them.

Because the water is relatively shallow and calm, the researchers can reach the sites via canoes. Still, when they were diving last March, onshore observers suggested they were crazy to work in the chilly water. During another outing in August, the conditions were more inviting and the water was closer to the temperature, not just the color, of warm tea.

“The water is beautiful today,” Smith says during a break. “Back in March it was about 45 degrees.”

They didn’t have to paddle far or dive deep. They concentrated on the remains of an iron hull sticking out of the water about 20 feet from the shoreline beside a two-story house. A dock actually extends over and beyond the ragged iron sides of the ship.

“It’ll be over my head,” notes Eric Ray, another ECU student, who stands about 6 feet 4 inches. The divers feel their way through murky water about eight feet deep as they take measurements and jot down observations about the ship’s construction.

Smith plans to learn more about the 100-foot vessel, apparently the remains of a steamer. Studying the way the ship is put together will give her a time frame for its origin. The wreck is not likely to yield artifacts, she says, because vessels were often stripped of machinery and valuables before they were abandoned. Scavengers picked over them after they sat in the water.

While the abandoned vessels remain frozen in time, or at least mired in the mud, the waterfront surrounding them continues to modernize and change. A sleek sailboat rocks gently at the dock nearby. Occasionally small fishing skiffs and powerboats speed along the channel. Across the river, the shoreline is lined with condominiums, as well as docks and marinas that are home to sailboats and yachts.

Modern Waterfront

The Elizabeth City waterfront, now nicknamed the Harbor of Hospitality, primarily caters to recreational boaters these days. “It has changed so much I don’t think many residents remember it as a working waterfront,” Smith says. Even when people recall events, it isn’t always written down for future generations, she adds.

The vessels scattered around Elizabeth City make up a collection of ships with diverse functions ranging from canal steamers to smaller coastal craft. In an outline of her research for Sea Grant, Smith notes the area “represents an extraordinary opportunity to study abandonment behavior patterns and site formation processes in an urban setting in order to illuminate historic trends in marine technological adaptation, the economic environment, as well as prevailing social behaviors that is not likely found elsewhere in the state.”

“By looking at this collection of watercraft as a microcosm of forces within maritime trading systems in the U.S. eastern seaboard,” she writes, “researchers hope to reconstruct and analyze the now defunct maritime commerce systems that drove the development of the state of North Carolina and its trading partners.”

Faculty and students in ECU’s maritime studies program have been studying graveyards for local and international ships for years. Another project, also partially funded by Sea Grant, focused on abandoned boats around the Pamlico and Pungo Rivers farther down the coast. That study looked at abandonment in a fishing community rather than an urban setting.

Nathan Richards, a faculty member in the ECU program, says the boat graveyards in the Pamlico and Pungo area involved places where people had a “living memory” of the boats. The vessels in the Pasquotank are much older and more of a challenge for interpreters, he says. “For us, these collections that are more mundane are telling us about the people,” he says.

Recalling How It Was

Elizabeth City resident Cecil Richardson, 84, is one of the old timers who can still remember when the city’s waterfront teemed with tugboats, barges and workboats. He recalls when fishermen from the Outer Banks came to sell oysters right from the boats and farmers tied up to sell their watermelons. “I’ve seen boats tied up two or three abreast,” Richardson says.

Barges kept wood moving to lumber mills that dotted the downtown area along canals that have long since been filled in. He says several large barges tied up and left to rot in the area waters were once known as “Bay Barges” in their working days.

Barges are rare around the waterfront these days. Once a week, a 58- by 200-foot barge towed by a tug boat hauls wood chips from the J.W. Jones Lumber Co.

“We’re the only ones that barge out of here now,” says Woody Bailey, manager of the chip mill.

Bailey has heard plenty of stories from Richardson, his father-in-law, and has observed more recent changes in the waterfront. He shares an album of photos with a visitor and recounts local lore.

Bailey says he’s glad to see the researchers probing the old wrecks. “It helps preserve the history of Elizabeth City,” he says. “There’s no telling what they’ll find.”

This article was published in the Holiday 2009 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: