The Catastrophic Power of Hurricane Helene

North Carolina's New History of Record-Breaking Storms

Only six years separate Florence and Helene, but these “once-in-a-thousand-year” hurricanes have much in common. Along with other storms that have hit our state, Helene offers lessons — and a warning.

Ed. note: The print edition of the Fall issue was already at press when Helene devastated western North Carolina, but the NC State Climate Office’s Corey Davis provides context for the record-breaker in this special online-only feature.

The scenes of significant flooding and outright devastation in western North Carolina after Hurricane Helene felt on one hand unimaginable, but on the other, quite familiar.

While Helene exceeded all historical flood events for most of the mountains, it wasn’t too long ago that a similar record-breaking storm hit eastern North Carolina with more extreme rainfall amounts that we believed were possible.

Hurricane Florence in 2018 became our state’s wettest and costliest tropical storm on record, and while it should narrowly keep that first title, the damage from Helene seems like it will inevitably surpass the $17 billion cost associated with Florence, as estimated by the governor’s office.

Both storms have rightfully assumed positions as the worst in their respective regions: for Florence, in eastern North Carolina, and for Helene, in the west. But the similarities don’t end with those superlatives.

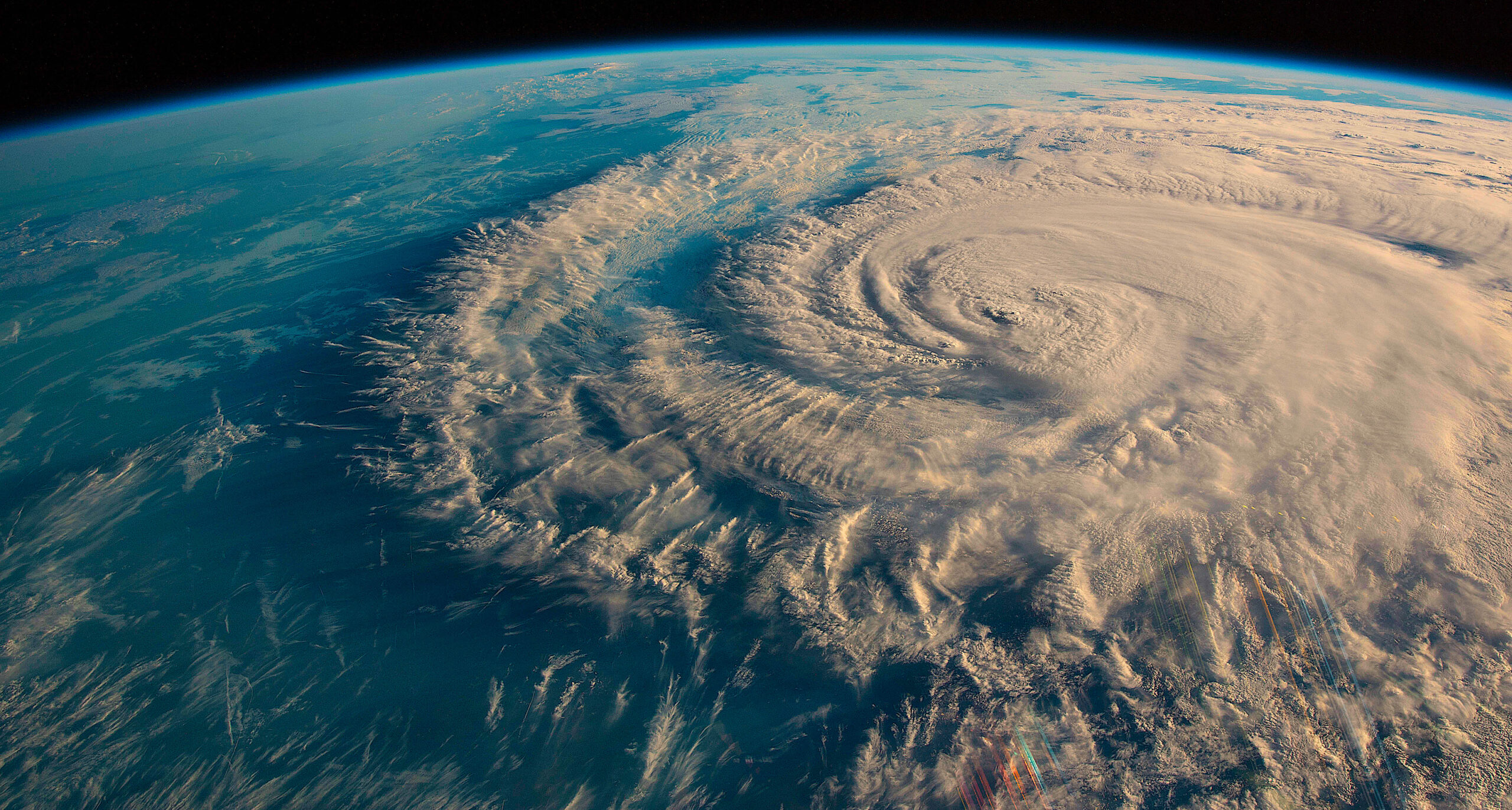

Strength at Sea

Florence and Helene both reached Category-4 strength at their peak, and they each did so in a hurry. Florence took just 30 hours to go from Category 1 to Category 4. Helene needed only 18 hours to make the same jump in its maximum sustained winds.

While Florence ultimately weakened back to a Category 1 before making landfall, that came at the cost of its sinister slowdown that ramped up rainfall totals across our state.

Before heading for western North Carolina, Helene held its strength over record warm water in the Gulf of Mexico and pounded the Gulf Coast of Florida with a 15-foot storm surge. That was on par with what North Carolina’s only known landfalling Category-4 hurricane did along our southern coastline. Seventy years ago in October 1954, Hurricane Hazel brought an 18-foot surge in Calabash and produced hurricane-force wind gusts as far inland as Raleigh. (Read Bland Simpson’s story about Hazel in this issue.)

Extreme Rainfall

With both storms, the damage didn’t stop at the coastline. Inland areas received the brunt of the impact due to heavy rainfall, the likes of which we’d never seen before in those corners of the state.

As Florence crawled across the Carolinas six years ago, easterly winds around the storm pumped in tropical moisture that fell as heavy rain — more than a foot, and as much as 3 feet — in southeastern North Carolina.

In tandem with a stalled cold front over the southern Appalachians, Helene also dropped more than 12 inches of rain over a wide swath of the mountains from Boone through Brevard. The highest reported three-day total after Helene of 31.33 inches in Busick made it only the second known storm in our state’s history to produce localized amounts of more than 30 inches.

The first, of course, was Florence.

In both cases, those extreme totals were literally off the charts compared to anything we’d experienced historically, or even expected was possible. NOAA’s Atlas 14 product, which contextualizes weather observations, characterized the 30-plus inches of rain from Florence in Lumberton and Wilmington, along with 3-day totals from Helene of 14 inches in Asheville and 24 inches at Mount Mitchell as well beyond local “1-in-1000-year” rainfall events.

We’ve now had two such events in our state — along with the “1-in-500-year” Potential Tropical Cyclone Eight just three weeks before Helene — in the span of just six years.

The Scale of the Flooding

Perhaps even more extreme than the highest rainfall amounts were the sizes of the regions during Helene and Florence that received rain and the degree of flooding that followed each storm.

Florence’s two coastal predecessors, Hurricane Floyd in 1999 and Hurricane Matthew in 2016, each produced locally heavy totals of more than 18 inches across a county or two. But Florence itself dropped amounts that high — and up to twice as much — across more than a dozen counties.

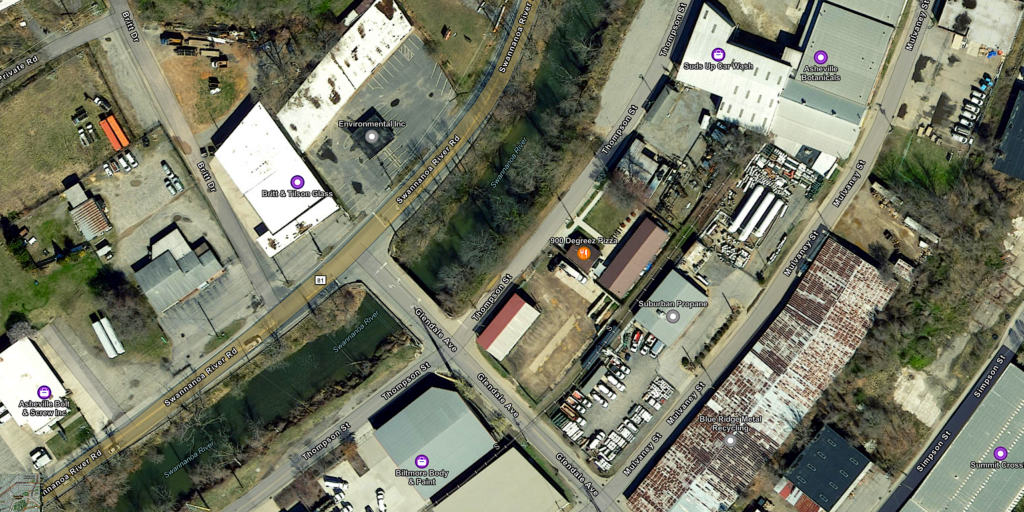

Likewise, in western NC, those highest amounts had historically been isolated to our highest points in the mountains, such as the 22.22 inches in 24 hours at Altapass during the legendary July 1916 storm. But with Helene, high amounts fell across the entire landscape — from 20 inches in the Asheville suburb of Black Mountain to nearly 22 inches near Hendersonville and more than 2 feet in Spruce Pine.

That much water, everywhere, couldn’t be absorbed by the soils — which, in the mountains, created another hazard as the saturated ground gave way in landslides — so it ended up in streams and rivers.

When those filled up as well, excess water spilled into towns and onto roadways, including interstates and major highways that left the region unnavigable. During both Florence and Helene, the North Carolina Department of Transportation advised that the hardest-hit regions of the state should be considered closed, and the major city within each region — Wilmington then, and Asheville now — was cut off for days or weeks following each storm.

A New High-Water Mark

Over the two decades prior to Florence, eastern North Carolina had endured freshwater flooding impacts from both Floyd and Matthew, each of which caused rivers to rise and inundate the towns along their banks such as Princeville and Lumberton.

But amplified by its more extreme rainfall totals, the flooding from Florence set new record high crests along the Cape Fear, Lumber, and Trent rivers.

The water levels in the wake of Helene also surpassed those from some well-known events in western North Carolina. The French Broad River in Fletcher crested 10 feet higher than its previous maximum from the July 1916 flood — an event that stood as the flood of record for more than a century in the Asheville area.

More recently, the remnants of Hurricane Frances in September 2004 also produced flooding in parts of the southern and central mountains. But the rainfall totals from Helene — which were almost three times greater than in 2004 in Asheville, and nearly twice as high in the upstream catchment of the French Broad river basin — helped push the flooding even higher.

Questions of Recovery

Today, in coastal towns such as Pollocksville in rural Jones County, muddy marks remain 6 feet high on the walls of downtown buildings, which sit empty and abandoned. Such scars are reminders of the challenges of recovery and that rebuilding requires more than just time.

The fixes for substantial damage to structures, as well as required updates to meet new local floodplain management regulations, have been too costly for many homeowners and business owners to undertake, especially after the third flood in the past 25 years in some areas.

Florence devastated the Columbus County town of Fair Bluff, and after five years of struggling to get people to come back, along with more flooding from events such as Tropical Storm Idalia in 2023, the town announced its would rebuild its downtown area on higher ground a few blocks away from the flood-prone banks of the Lumber River.

For western NC towns that now face a similar reality, they’ll have to confront the same questions about how and where to rebuild.

Of course, many places in that region don’t have the same luxury of space as in the flat, expansive Coastal Plain. Chimney Rock, for example, is sandwiched between two steep hillsides along the Broad River, making it difficult to move to higher ground — and even there, those same slopes turned into the flows of mud and debris that wiped out much of the town during Helene.

A Sign of the Future

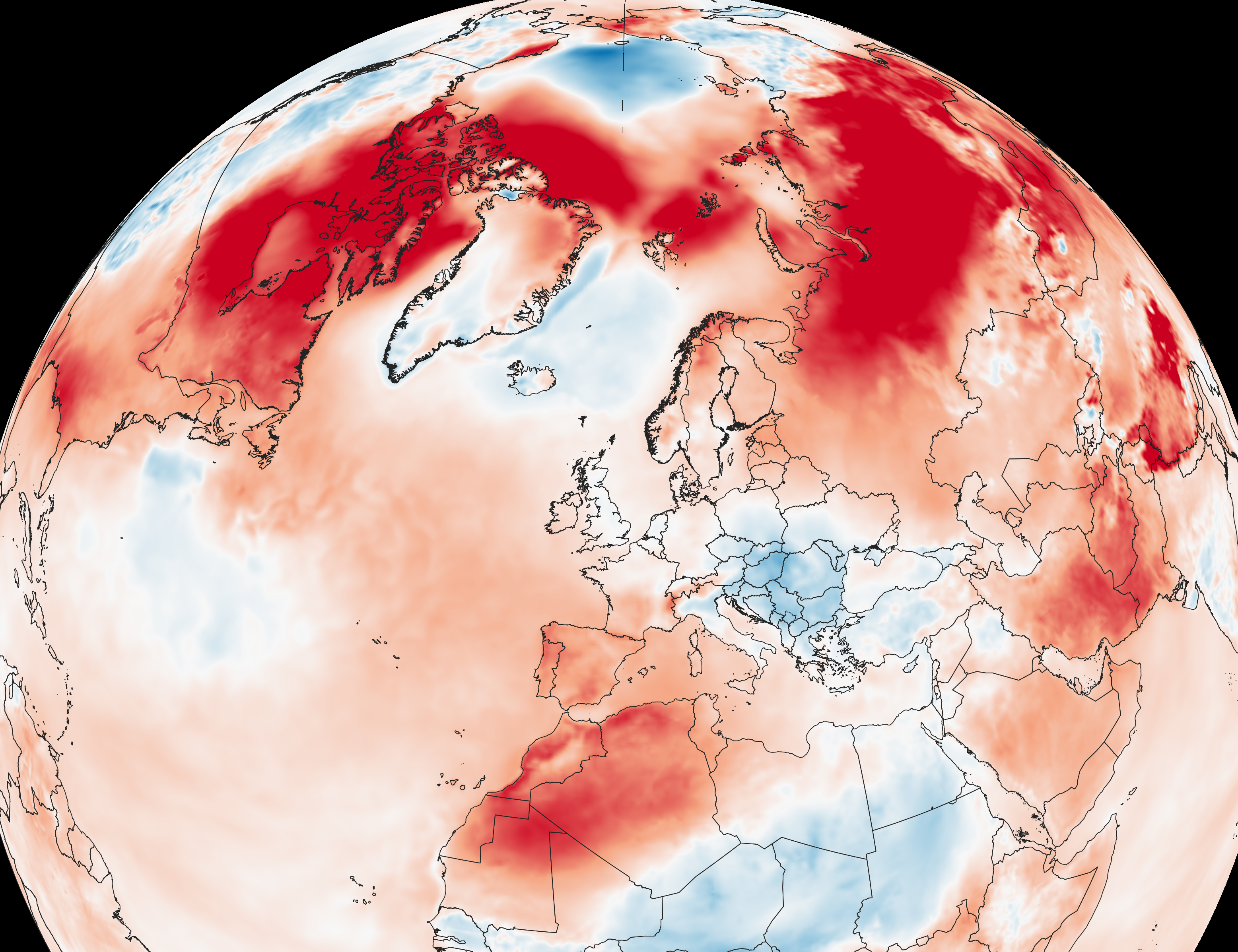

There’s a common thread behind many of these similarities, and it’s one that’s getting harder to ignore or deny amid our increasingly extreme weather.

The rapid intensification of Florence and Helene over historically warm water, the atmosphere’s ability to support the ample amounts of moisture that fed unprecedented rainfall totals, and the flooding that followed as months’ worth of rain fell in just a few days are all known consequences of climate change.

Storms like Florence and Helene probably will happen again, perhaps with an even greater magnitude. Researchers at NC State University simulated Florence in a warmer end-of-century environment and found its maximum rainfall totals would be 46% greater — upwards of 56 inches — and the area receiving at least 20 inches of rain would almost double.

That means Florence’s and Helene’s places all alone in the upper echelon of our state’s most damaging storms won’t go unchallenged, despite their record rainfalls, costs, and death tolls.

And it means the reality of rebuilding — and smartly — is more important now than ever before, whether it’s in the coastal communities still marred by Florence or the mountain towns now facing a long, steep road after Helene.

MORE

Corey Davis also wrote a “Rapid Response” article about Hurricane Helene for the NC State Climate Office.

Read the North Carolina State Climate Office’s “Stormy Summer” series on notable hurricanes here.

Corey Davis is the North Carolina’s State Climate Office’s assistant state climatologist. In addition to writing for the office, he also serves as editor of its blog, creates monitoring tools, and represents the office on the NC Drought Management Advisory Council.

- Categories: