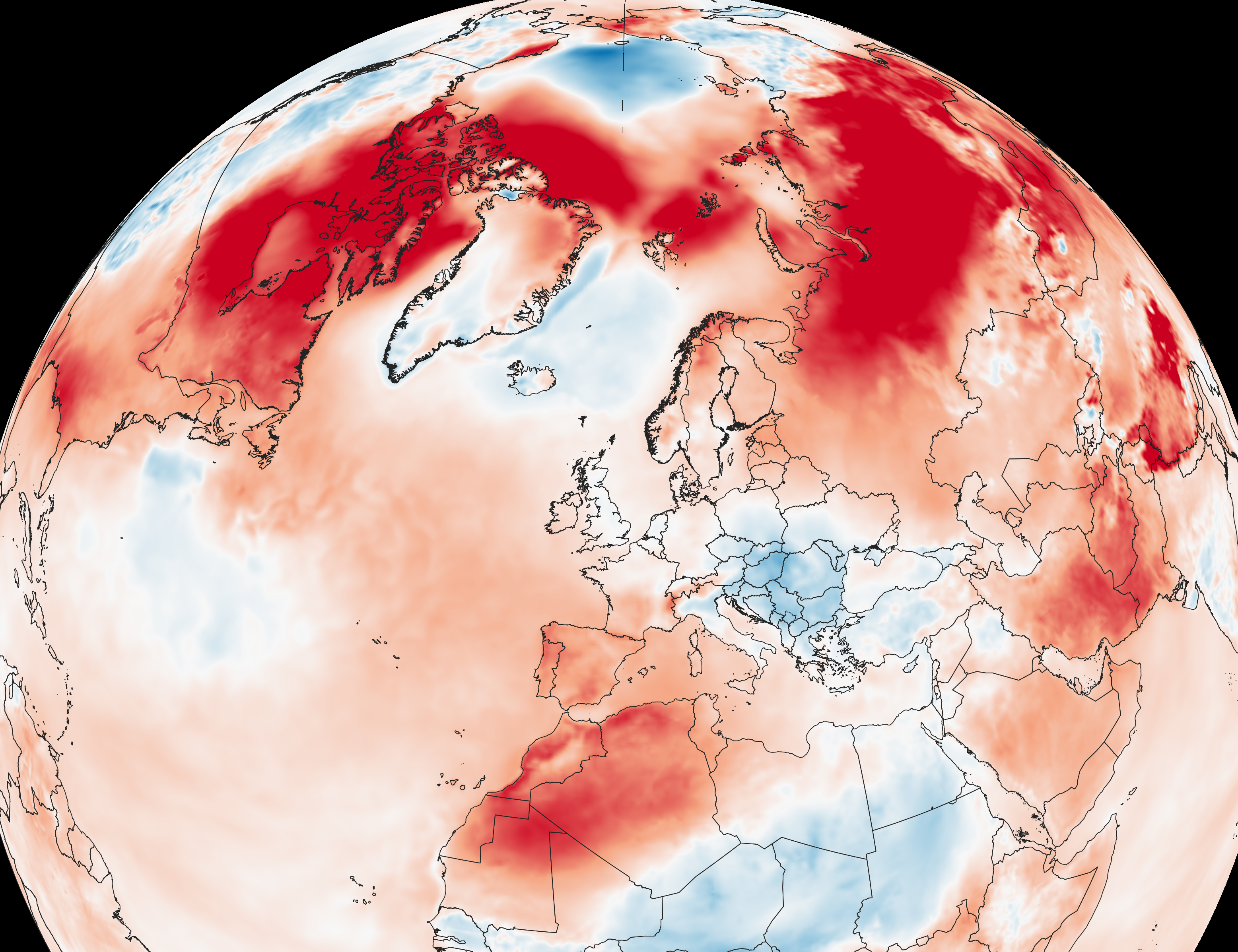

As emissions reach all-time highs, far more stringent goals are necessary to keep global warming under a threshold that would make heightened climate impacts unstoppable.

The UN Environment Programme’s 2024 Emissions Gap Report calls for immediate and more significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions to limit global warming.

What Is the Emissions Gap?

The emissions gap refers to the difference between goals for emissions levels and what scientific evidence says will be necessary to limit the rise in global temperatures to the Paris Agreement’s target of 1.5°C (2.7°F).

The Emissions Gap Report also addresses the gap for slowing warming to a maximum of 2°C (3.6°F). Experts use 2°C as a less desired upper limit since slowing temperature rise between 1.5°C and 2°C will still have a detrimental impact on the environment. Potential effects include extreme heat, continued rapid sea-level rise, further intensification of natural disasters, and near complete destruction of coral reefs.

However, these changes are survivable. If warming exceeds 2°C, though, environmental changes will continue to intensify at accelerated rates, and damage to the environment will become unstoppable and irreversible.

Given current estimates, by 2030 a 42% decrease in global emissions would cap global warming at 1.5°C. To limit to 2°C, emissions must decrease by at least 28%. As it stands, achieving the Paris Agreement’s current goals will not close the emission gap, and global warming will rise above the 2°C threshold by an additional 0.6°C to 0.8°C over the course of this century.

Emissions Reach Highest Levels Yet

In the most recent estimates (2023), experts measured the highest amount of greenhouse gas emissions to date, equivalent to 57.1 gigatons of carbon dioxide. This is a 1.3% increase from 2022, a higher rate of increase than the average in the decade preceding the COVID-19 pandemic (0.8% per year). A majority of these emissions (68%) come from fossil fuels, which grew by 2% (0.3% more than the growth in 2021 and 2022).

The greatest contributor to these emissions is the combustion of coal, oil, and gas for the generation and distribution of electricity. While there are steps in place to decrease these emissions — such as improving efficiency (which reduces necessary electricity use) and using lower-carbon or non-fossil fuel alternatives — these changes do not offset global emission levels.

The report recommends a greater commitment to “decarbonizing,” the change to non-fossil-based fuels, especially in the generation of electricity.

Major Actors in Global Emissions

Contributions to global warming are not evenly distributed. The Group of 20 (G20) — an intergovernmental organization comprised of 19 countries, the European Union, and the African Union — contributes over three-quarters (77%) of current emissions.

Although the G20 supports the global economy and tackles issues of global concern, key members include the top five producers of greenhouse gas emissions in 2023: China, the United States, India, the European Union, and the Russian Federation.

China produced the highest emissions, contributing 30% of total global emissions, but ranked third in per capita emissions. The United States ranked second for both total contributed emissions and per capita emissions. India was third in total emissions but had the lowest per capita emissions of this group.

The combined emissions of the 27 countries of the European Union ranked fourth, with 6% of global emissions, as well as fourth in per capita emissions. Finally, the Russian Federation was fifth with 5% of total global emissions, but first with the highest per capita emissions.

With the exception of India, these top contributors produced significantly more emissions than the global per capita average. Additionally, these five members of the G20 have produced 54% of all greenhouse gas emissions historically.

Last, the least developed countries, many of which are a part of the African Union, were minor contributors to global emissions, accounting for only 3% of total greenhouse gas emissions.

Next Steps for Closing the Emissions Gap

All countries must take the same first step to mitigate climate change: emission “peaking” – when a country’s emissions rate has reached its highest level and then either plateaued or fallen below that level for at least 5 years. The report emphasizes that countries should aim to “peak emissions as soon as and at as low a level as feasible.”

Currently, seven G20 members are yet to reach their emissions peaks (China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Republic of Korea, Saudi Arabia, Türkiye), and of the 10 that have peaked (Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, European Union, Japan, Russian Federation, South Africa, United Kingdom, United States), only two are likely to achieve their emissions targets as the Paris Agreement defines them.

In fact, current targets will only reduce emissions 4-10%, falling far short of the 28-42% necessary to slow warming to 1.5°C.

Despite the immense scale of the task ahead, the Paris Agreement’s original goals are technically achievable, but action must be immediate and will incur a cost. Current estimates of the cheapest strategies have found that it would take about $200 to remove one ton of the 57 billion tons of emissions released in 2023.

According to the report, transitioning to lower cost options, such as solar power and wind energy, can deliver 27% of the needed emission reduction for 2030, and 38% for 2035. Currently, the United Nations Environmental Programme is calling for countries to revise their goals and join it in demanding “no more hot air.”

More

Ice to Ocean: From the Sources of Sea Level Rise to the Coast of NC

Vital Signs: Greenhouse Gas Emissions Hit Highest Levels

50-year Trend in Atlantic Hurricane Escalation

More from Coastwatch on climate change

Lily Soetebier is a contributing editor for Coastwatch and a science communication intern at the North Carolina Sea Grant. She is pursuing an M.S. in technical communication from North Carolina State University.

lead photo: adobe stock.

- Categories: