Emily White is a former North Carolina Sea Grant communications intern. She is a senior at NC State University, majoring in science, technology and society. Page excerpts from North Carolina’s Amazing Coast: Natural Wonders from Alligators to Zoeas.

Monogamous pairs. Fathers who carry the eggs. Murderous siblings.

North Carolina is home to animals that have developed a multitude of ways to care for their young. Some of these adaptations are well known to humans. Others? Not so much.

These behaviors and social patterns, the familiar and the unfamiliar, are part of what makes North Carolina’s coastal species so intriguing and diverse.

Much of the species variety can be attributed to how our coast is situated, explains Terri Kirby Hathaway, North Carolina Sea Grant’s marine education specialist.

“Cape Hatteras is the boundary between two biogeographical regions. We are the northern extent of many southern species’ range and the southern extent for many northern species’ range.”

A wide range of family and group dynamics among species is featured in North Carolina’s Amazing Coast. Hathaway is a co-author of the book that introduces 100 of North Carolina’s flora and fauna by describing some of each species’ unique attributes.

• MONOGAMOUS MATES

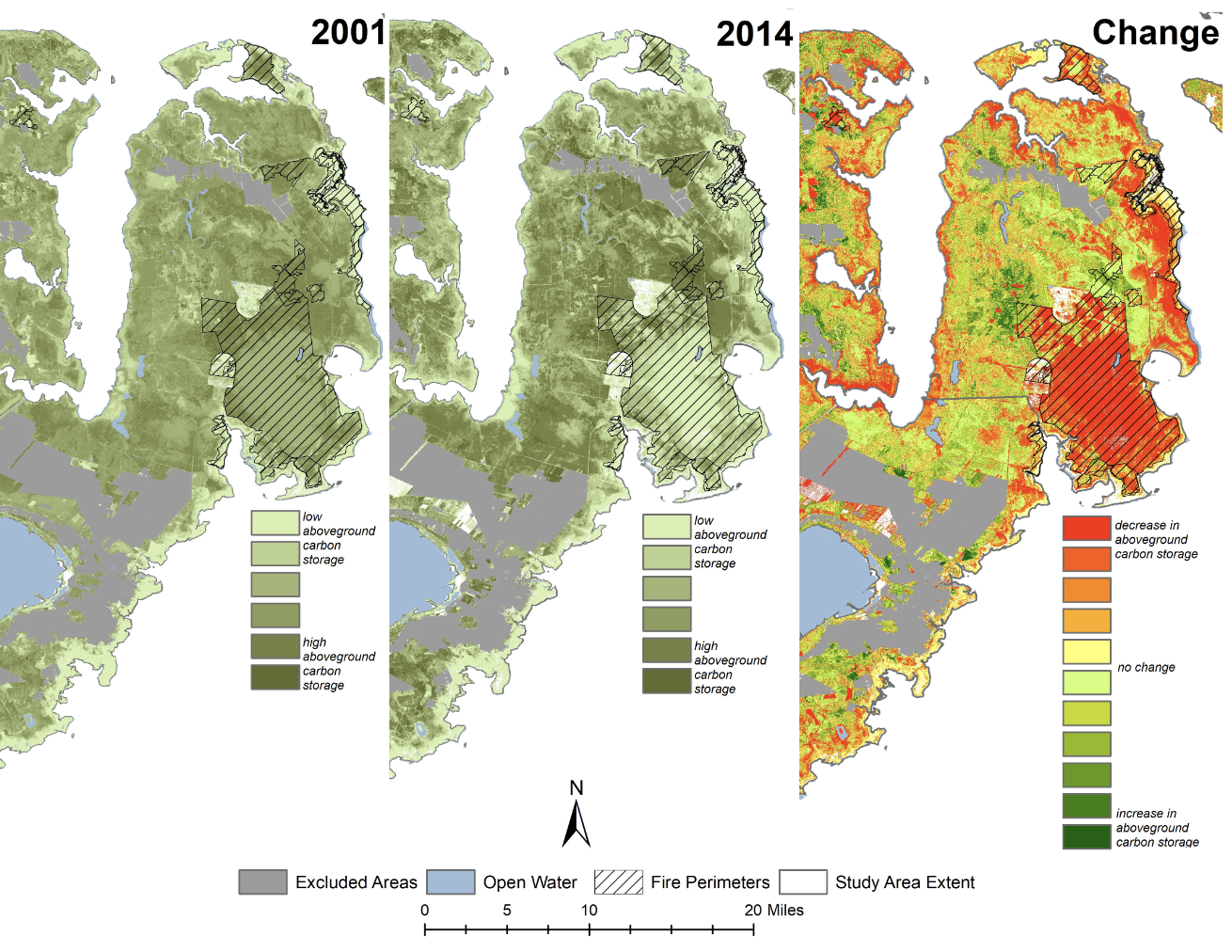

Male and female white ibises, Eudocimus albus, form monogamous pairs and work together to build homes for their young. Their nests may be made of sticks, grass or reeds. The white ibis breeds year-round on small coastal islands.

Versatile and highly adaptable, the white ibis can thrive in many environments. These graceful wading birds can be found in swamps, marshes and even city parks. Their long, down-curved bills are well suited for searching mud for insects, crustaceans and small fishes.

According to Audubon North Carolina, the white ibis is naturally social, feeds with a flock and nests in a large colony of up to 14,000 pairs, often mingling with other wading species.

If they nest near salt water, they may travel 30 miles or more to find freshwater foraging habitat when raising young chicks.

• DANCING DADS

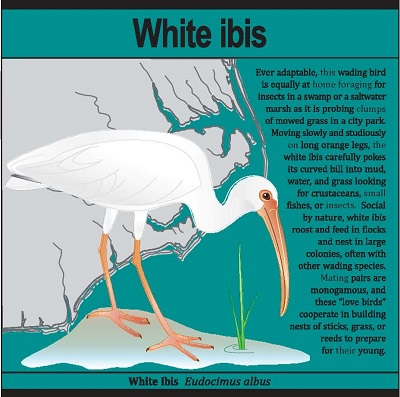

During breeding season, the male seahorse, Hippocampus erectus, will perform greeting dances for his female partner.

Shelley Anthony, an aquarist at the N.C. Aquarium at Fort Fisher, has observed this mating behavior while propagating seahorses bred in captivity. She also notes that competition can breed trouble in paradise.

“Although I cannot comment on their behavior in the wild, I have observed males grabbing each other’s tails and having a type of wrestling and posturing behavior, perhaps to show who is stronger and to impress the available females,” she notes. “I also have seen single males push in between a male-female pair during mating attempts, thereby preventing egg transfer.”

Individual seahorse pairs may change over time. If a mate dies or is lost, the remaining individual will seek another mate, she notes. “In addition, studies have demonstrated that while the males are generally more monogamous, if a female finds a more attractive male, she may leave her current mate and go with the new one,” Anthony adds.

She still is amazed at the variety of depths and habitats in which seahorses can be found.

“We have collected them in the Intracoastal Waterway, off Topsail Beach and as far out as 40 nautical miles offshore floating in Sargassum weed rafts,” she explains.

The seahorse is not a strong swimmer. Rather, it is uses a prehensile tail to cling to grasses and corals in estuaries and ocean waters.

It is also one of several animals in which the male carries the young.

• PREGNANT PAPAS

Another is the pipefish, Syngnathus spp. With long, skinny bodies and pipe-shaped mouths, many are surprised to learn that they are, in fact, fish.

“People usually think that they are a small eel or some type of sea snake. And they have no idea that they are closely related to seahorses,” Anthony explains.

But pipefish have greater variation in how the males carry the young. “Some species have internal pouches, like seahorses, and the process is pretty much the same,” she notes.

“Other species have pouch-like flaps or folds, and some just carry the eggs on a sticky patch underneath their tail.”

What determines the difference? “A general rule of thumb that I use is if the species is pelagic — it swims around without ever touching bottom — it has an external-type pouch or sticky patch. If it lives on the bottom, the pouch is internal to prevent the eggs from being scraped off.”

Within the pouch, the eggs hatch into embryos and develop into juveniles. As they develop, the pouch distends and the dedicated dad appears pregnant.

Average gestation time is three weeks, with about 50 young released in a batch, Anthony notes. “They are usually less than an inch long and look like human hairs floating in the water, except they are moving,” she describes.

• CATFISH CARRIERS

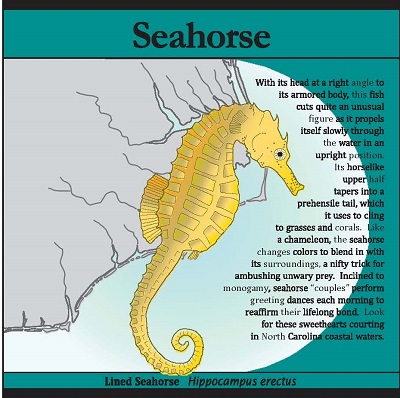

The gafftopsail catfish, Bagre marinus, is yet another example of a species in which the males do most of the child rearing.

The male fish incubates a batch of up to 55 eggs, each roughly an inch in diameter — and he uses an unusual place. The fish’s mouth provides the safety the eggs need to mature and hatch.

Once hatched, the young catfish remain in the male’s mouth until they grow to about 3-inches long and can take care of themselves.

The entire process takes around two months, and the males don’t feed throughout this process.

This fish, nicknamed the slime cat, is covered in copious amounts of mucous and has no scales. When hooked on a fishing line, much of this mucous rubs off on the line, leaving behind a slimy residue.

• SAVAGE SIBLINGS

The sand tiger shark, Odontaspis taurus, comes into the world as a seasoned predator. While in utero, the hatchlings’ teeth develop.

This allows the strongest hatchling in each of the two uteruses to devour eggs and smaller hatchlings, making the pair of dominant young sharks the sole survivors of the group.

After finishing off their siblings, the two sharks are born 2- to 3-feet long, ready to hunt their next meal. The juvenile sharks will eat almost everything, but their preferred diet is small fishes.

The adult sand tiger shark is known for its big appetite. This aggressive-looking species has been known to eat trash cans, burlap bags and even other sharks.

Chuck Bangley, a Sea Grant-funded scientist who wrote an article titled “Sharks of North Carolina” for the Spring 2014 issue of Coastwatch, notes that the sand tiger shark can grow to 12 feet and can be found year-round in North Carolina waters, especially around structures such as wrecks and live-bottom habitats. Read his full article at go.ncsu.edu/oi8qlo.

Despite their savage start and fearsome appearance, sand tiger sharks usually are docile around humans, which makes them popular with divers and aquariums.

Learn more about these and dozens of other species in North Carolina’s Amazing Coast: Natural Wonders from Alligators to Zoeas, available from ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/bookstore. Or find it in local bookstores.

Also, plan to visit one or more of the coastal sites for the North Carolina Aquariums. Locations, schedules and other information are at ncaquariums.org.

This article was published in the Winter 2017 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: