Coastal Storytellers Spin Fish House Tales and Other Whoppers

While standing in front of a fish house scene complete with rocking chairs, Rodney Kemp spins a whopper about a bolt of lightning turning North Carolina’s only menhaden plant into a towering inferno.

The Beaufort Fisheries management called in fire trucks from all over Eastern North Carolina and as far away as Raleigh, says Kemp.

“Those fire trucks couldn’t get within 100 feet of the fire because of intense heat and watched it burn,” relates Kemp to an audience at the 2003 Down East Storytelling Festival in Morehead City. “So finally the management of Beaufort Fisheries waved a check for $10,000 as a reward to the firefighting company that is successful in putting out the blaze.”

But not a single fire truck budged, he says.

“Suddenly, they heard a great commotion and turned just in time to see full bore — coming down Front Street — none other than the Cedar Island Fire Department,” adds Kemp. “Now the Cedar Island Fire Department was driving a 1952 double pumper.” With two buckets of sand, two ladders and three buckets of water they put out the blaze.

When asked what he would do with all the money, the first thing the chief said was to take the old truck and fix them brakes, Kemp adds.

As one of the original “fish house liars,” Kemp has told the “Cedar Island Fire Department” tale dozens of times.

“When you start telling stories like I do — and people halfway believe you — they give you a label, a term of endearment,” he says. “People started calling me a common fish house liar.”

A group of about eight men started telling tall and dubious tales around 1991 and were dubbed fish house liars by master storyteller Josiah Bailey. Today, Kemp and Sonny Williamson of Marshallberg still are spinning tales in Carteret County.

“The tales we tell as liars are the same stories which have been passed down verbally from generation to generation,” Williamson writes in Fish House Lies. “Over the years, they have been added to, modernized and changed until the only truth remaining is that they are intended strictly for entertainment and, even though we sometimes poke fun, it is never done with malice. This is important to remember because that’s what it’s all about, to just have good, clean fun.”

Varied Styles

Although both Kemp and Williamson are fish house liars, their styles differ. Williamson has a Down East storytelling style in comparison to Kemp’s “Southern style” that is similar to the late comedian Jerry Clower and the late newspaper columnist Lewis Grizzard, says Kemp.

Across North Carolina, there are many storytelling styles.

“Every region is different,” says Kemp. “People Down East in Carteret County don’t understand mountain Jack tales.”

However, Down Easters do have a gift for telling stories, according to North Carolina State University professor Carmine Prioli, who wrote Hope for a Good Season: The Ca’e Bankers of Harkers Island. “They all have natural instincts for storytelling,” says Prioli. “When they get on a roll, there is no stopping them.”

For years, Capt. Jim Willis of Salter Path has been telling Down East stories.

Dressed in a khaki jumpsuit and fishing cap, Willis calls himself a “Banksologist” because he studies the Outer Banks and specializes in the Bogue Banks that includes Atlantic Beach and Salter Path.

“True Banks tales don’t have no name,” says Willis. “I have broke with tradition and give my stories names. I studied at the University of Salter Path under Dr. Little George Smith and Professor Bryant Guthrie of the Promise’ Land.”

A five-block area in Morehead City is dubbed the Promise’ Land by those who migrated from Ca’e Banks, where the Cape Lookout Lighthouse stands.

Willis uses the Banks brogue when telling tales, including “Unquenchable Thirst” about a Banker who loved any kind of whiskey.

Storytellers in Carteret County spin many stories about alcohol.

In the shade of weeping willows in front of his Core Banks cottage, David Yeomans often entertains tourists by crooning “The Booze Yacht” – a ballard about a whiskey boat gone aground.

“I learned this from my father who was a storyteller,” says Yeomans. “He wrote some things and told stories sometimes. He would tell stories at fish houses.”

Coastal Legends

Along the coast, storytellers also entertain audiences with ghost, pirate, hunting and Indian stories.

One popular tale is “Maco Light,” set in 1867 in Maco — about 15 miles outside of Wilmington in Brunswick County. After a caboose dislodged, conductor Joe Baldwin waved a light at an approaching freight train, according to North Carolina Legends, edited by Richard Walser. As the train plowed into the dislodged caboose, it decapitated the conductor’s head.

“Thereafter on misty nights, Joe’s headless ghost appeared at Maco,” the legend goes. During an 1899 campaign trip, President Grover Cleveland reported seeing the light — and so have hundreds of people through the years. But in 1977, the railroad tracks were removed and the swamp reclaimed the haunting grounds. “Joe seems to have lost interest in Maco. At least he has not been there lately,” the legend ends.

On Ocracoke Island, stories of Edward Teach — also known as Blackbeard the Pirate — abound. They include “The Pirate Lights of Pamlico Sound” in Charles Harry Whedbee’s Legends of the Outer Banks and Tar Heel Tidewater.

While on his ship the Queen Anne’s Revenge, Blackbeard shot and crippled his mate, Israel Hands, at Teach’s Hole.

Later, he battled the British while aboard another ship. Toward the end of the fight, a British sailor killed Blackbeard and cut off his head, according to the legend.

“To this day at Ocracoke, some will tell you that the ‘Teach lights’ are still seen on occasion both over and in the waters of Pamlico Sound,” writes Whedbee. Blackbeard’s ghostly ship is sometimes seen in the light of the waning moon. Some say the headless figure of Blackbeard can been seen in the dark of the moon as the body swims around and around Teach’s Hole, searching for its severed head.”

Storytelling History

Throughout coastal North Carolina, storytelling has become an art form.

Years ago, people gathered at country stores, fish houses and front porches to exchange tales. One popular spot on Harkers Island was Cleveland Davis’ store called “the beehive.”

One storyteller, Grayden Paul of Beaufort, earned a reputation for his innate ability to relate tall tales.

“Grayden Paul was the best storyteller I ever heard,” says Kemp. “He performed in the 1940s, ’50s, ’60s and ’70s. He had a regular routine and amazing stories.”

Today, people tell stories at festivals and family reunions.

“I love storytelling,” says musician and storyteller Connie Mason. “People are hungry for it with e-mail and electronic devices. Storytelling is personalized.”

For Ocracoke storyteller Donald Davis — who has performed all over the world, including the Smithsonian Institution — storytelling is a “way of giving and living life.”

“He invites each listener to come along, to pull deep inside for one’s own stories, to personally share and cocreate the common experiences that celebrate the creative spirit,” Davis recounts on his Web site.

In a few small communities, residents also spin yarns at restaurants and other hangouts.

Each morning, a group of men gather at a round table and tell tales at the Heritage House in Windsor.

“Most of the time the men tell stories about farming, fishing and hunting, and how things were a long time ago,” says Rachel Pierce, the restaurant’s co-owner. “Some come as early in the morning as 5:30. They have been friends forever, and all are retired and natives of Bertie County.”

Liars Club

In the tiny community of Powellsville near Ahoskie, members of the Scrub Club — which is made up of about 20 retired men – swap tales every weekday at a closed gasoline station on N.C. 42.

“Everybody tries to top somebody else,” says Buck Carter, the club’s treasurer. “You tell the biggest lie you can think of. Others are supposed to tell a lie bigger than yours so people will believe it.”

One of Carter’s favorite lies is about a squirrel that he saw while hunting.

“The squirrel was pushing bark back into the water,” he says. “When the squirrel got to the water, it jumped in, pushed its tail up, and the wind blew it across the water. Then it jumped up the tree on the other side.”

After Carter told the tale, another man topped the story.

To keep the group from disbanding, members have to follow a few rules. “We don’t allow anyone who works,” says Carter. “It is a bad influence. We don’t talk politics or religions. We don’t want to have a falling out.”

Although storytelling offers local folks a quaint form of entertainment and an interesting pastime, it also links them to their past, according to Jack Thigpen, North Carolina Sea Grant extension director and coastal and tourism specialist.

“These stories also give a glimpse into a region’s culture and history,” says Thigpen. “Often important moral values and shared virtues are interwoven with humor.”

What makes a good storyteller?

Whether spinning fish tales or historical vignettes, a good storyteller believes in what he is doing and enjoys it, says John Golden of Wilmington.

“Beyond that, the sky is the limit,” he says. “I am continually developing different ways of telling a story — from sitting in a chair for a classical tale to a living history performance of folklore and legends.”

School Performance

For a group of students at Cooper Elementary School in Clayton, Golden dressed like an Elizabethan sailor in a white belted shirt, olive green breeches and tan moccasins.

“I am a minstrel bringing news from 400 years ago from Queen Elizabeth’s court,” he says.

“Queen Elizabeth never married, and men were coming to her court to impress her,” says Golden. “She was the most powerful woman in the world and had a great armada of ships.”

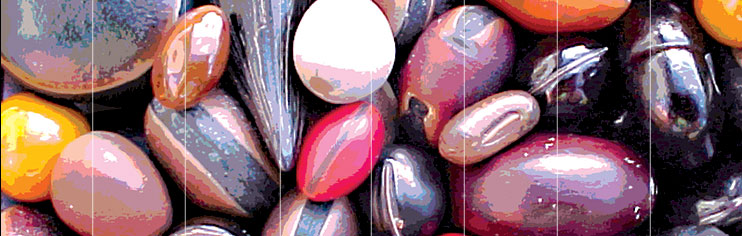

Golden asks the students to sing “Froggy Went A-Courting” with him. Later, he engages the students with bean games and more tales about Sir Walter Raleigh’s voyage to the New World.

At the end of the performance, Golden strums his guitar while singing “Virginia Dare.”

“I wrote these words to tell the sad story of the mysterious fate of the little girl to go along with the beautiful melody composed by my songwriting partner, Rob Nathanson,” he says.

Ann White, fourth grade teacher, says that the historical tale was perfect for her students who are learning North Carolina history.

“They have heard the legend of ‘Virginia Dare the White Doe,’ ” says White. “This is a good culminating activity. For the fifth graders, it reinforces what they have learned. It gives the third graders a good introduction to our state’s history.”

For younger students, Golden relates less serious subjects like animal tales. “I tailor my stories to the audience,” says Golden.

Sound Country Stories

When spinning yarns about the coastal plains, Chapel Hill author and musician Bland Simpson draws on his roots in Pasquotank County.

“I learned stories from my father who was a lawyer and a good yarn spinner and also in the Merchant Marine and Navy,” says Simpson, a member of the Red Clay Ramblers.

In the book Into the Sound Country: A Carolinian’s Coastal Plain, Simpson relates childhood memories, including that of his father “coming home at breakfast time with a brace of ducks from his first-light Currituck hunts.”

His stories and songs also draw inspiration from North Carolinian John Harden’s The Devil’s Tramping Ground and Other North Carolina Mystery Stories and Nell Wise Wechter’s Taffy of Torpedo Junction.

These books were Simpson’s and his schoolmates’ “first literary inklings that real and noteworthy things of history — and mystery — had occurred right in the small towns and country crossroads where we lived, and that the telling and retelling of these stories in classrooms and living room were no small part of what bound us together as Tar Heels, as Southerners, and as Americans,” Simpson wrote in the foreward to the 1996 reissue of Taffy.

Want to hear more coastal tales? Rodney Kemp and Sonny Williamson will perform together on Oct. 4 at noon at the 17th Annual N.C. Seafood Festival in Morehead City. For more information, visit the Web: www.ncseafoodfestival.org.

This article was published in the High Season 2003 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: