Conserving a Culture: Land Development, Climate Change, and the Gullah/Geechee Nation

“We teach our children the same traditional ways to go out in the water, and the same traditional ways to live from the land: only when things are in season.”

“Gullah/Geechee communities are typically found in areas where there are remnants of rice, indigo, and cotton. The culture is unique in that because of the seclusion found in those areas, people have been able to retain many West African traditions that aren’t found as often in other African American communities. The Gullah/Geechee people have been able to hold on to their roots.”

— Courtney McGill, program specialist at the University of Georgia’s Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant, and a member of the Gullah/Geechee Community

The Albemarle-Pamlico Sound region and communities southward along the Atlantic coast are home to millions of people — including nearly 500,000 residents of the Gullah/Geechee Nation, who inhabit a 500-mile stretch between Jacksonville, North Carolina, and Jacksonville, Florida.

The South Carolina coast sits at the heart of this terrain and is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the region. Nearly 7.3 million visitors flocked to the Charleston area in 2018 alone (as an indicator of its pre-pandemic popularity), pushing the economic impact of the region’s tourism to a record $8 billion that year. Hilton Head Island, one of South Carolina’s award-winning tourist destinations, itself typically attracts about 2.5 million visitors a year.

The Southeast coast also serves as an important foundation for the Gullah/Geechee Nation, whose people, over the years, have seen aspects of their culture vanish. With the increase in tourism comes more development of land, which, in turn, has displaced many important practices and beliefs of the Gullah/Geechee community.

The Gullah/Geechee Nation is also experiencing the heavy impacts of climate change on its waterways. The ocean traditionally has provided many resources and has brought the community food security.

As the effects of global warming and development both severely test the resiliency of the Gullah/Geechee people, is it possible to preserve this important nation and its culture? And, if so, how?

“DISYA WHO WEBE!”: LANGUAGE, FOOD, AND ART

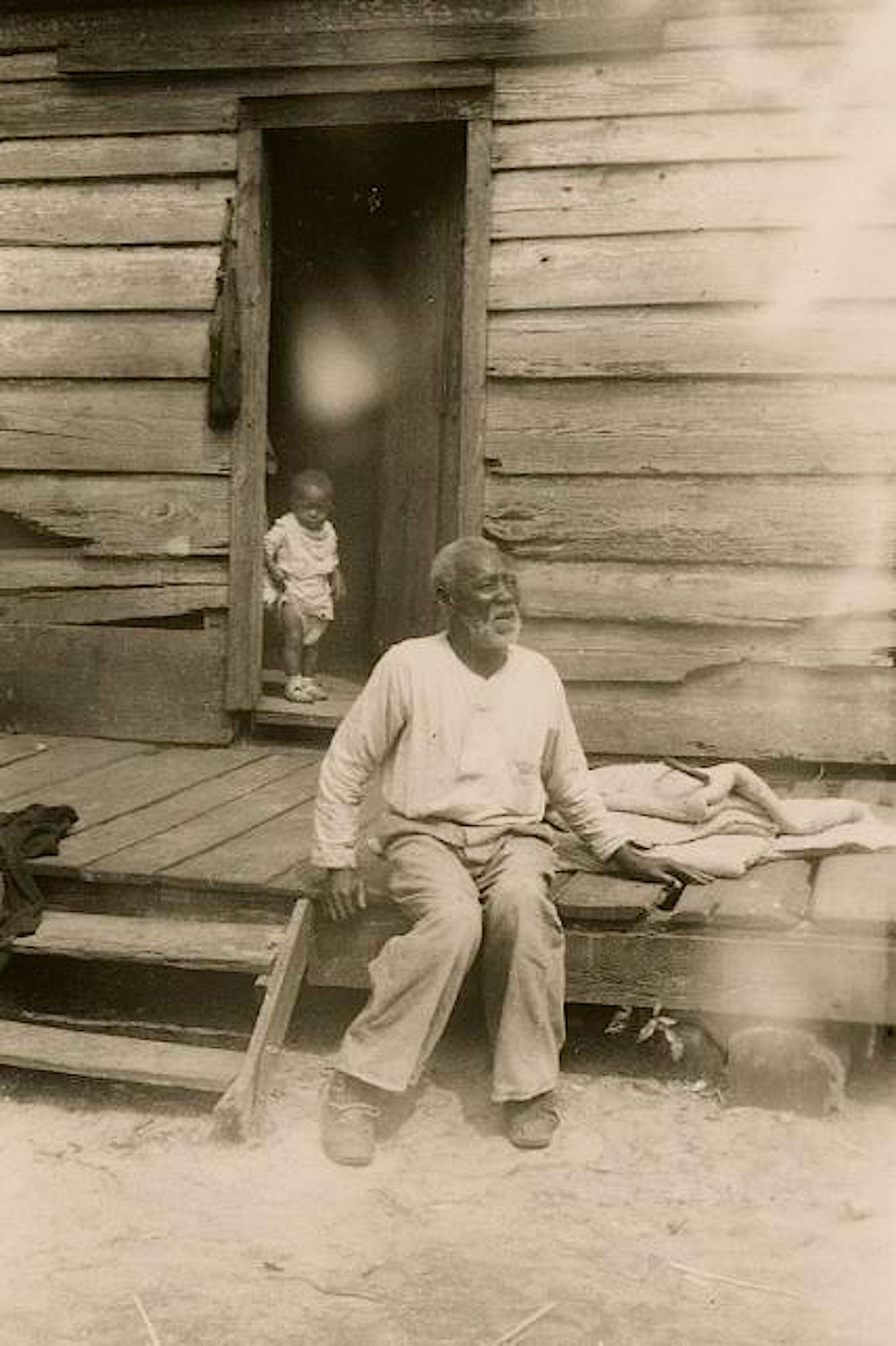

The Gullah/Geeche people are the descendants of Africans enslaved on multiple cotton plantations, known as the “Sea Islands,” located off the coast of South Carolina and southward into Georgia and Florida. Over time, enslaved Africans of different tribes and regions met and intermingled, leading to the emergence of the “Gullah” people.

The dialects they spoke among themselves created a place to uphold African culture, despite the conditions of slavery, and ultimately led to the creation of their own language, “Geechee” — a creole language specific to the coastal areas of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. According to the Gullah/Geechee Heritage Corridor, in fact, Geechee is the only distinct African creole language in the United States that has influenced traditional vocabulary and speech patterns in the South.

The history of the Gullah/Geechee is truly unique.

Courtney McGill, program specialist at the University of Georgia’s Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant, is a member of the Gullah/Geechee community. When she was a child, her mother married a 9th-generation Sapelo Island descendant, and her family moved to the island, off the coast of Georgia.

“Gullah/Geechee communities are typically found in areas where there are remnants of rice, indigo, and cotton,” McGill says. “The culture is unique in that because of the seclusion found in those areas, people have been able to retain many West African traditions that aren’t found as often in other African American communities. The Gullah/Geechee people have been able to hold on to their roots.”

Gullah/Geechee ancestors brought African cultural traditions in music, food, and art. Most of their arts and crafts are products designed for daily living, such as cast nets for fishing, basket weaving for agriculture, and textile arts for clothing and warmth.

McGill says the traditional diet of the Gullah/Geechee consists of vegetables, fruits, and seafood, including okra and peas, berries, and shrimp, crab, and fish.

“I have so many rich memories of seine net fishing with the entire community and having large fish fry cookouts with the catch of the day, learning how to make sweet grass baskets, listening to ‘griots,’ such as the late Cornelia Walker Bailey’s storytellings, and attending church, where we would participate in call and response worship services,” she recalls. “It is important for this culture to persevere, so that we maintain these connections to our ancestors and our history.”

Marquetta Goodwine, also known as Queen Quet, is founder of the Gullah/ Geechee Sea Island Coalition and the first elected Chieftess of the Gullah/Geechee Nation. She says that North Carolina Sea Grant’s “Quality Counts: A Consumer’s Guide to Selecting North Carolina Seafood” has helped the Gullah/Geechee become more aware about seafood safety today.

“It was great to have that little guide,” she says. “A person who was living or visiting the area knew what was safe to eat.”

VANISHING LAND

Back in the 1900s, land on some of the Sea Islands where Gullah/Geechee ancestors were once enslaved — including Cumberland, Jekyll, and Sapelo — became either resort locations or reserves for natural resources. This was the precursor to modern-day conflicts over resort development.

Surviving members of the community have taken many measures to help maintain and protect their culture, holding onto the traditions that their African ancestors brought to America, as well as legally obtaining and staying on the isolated former plantation lands where their ancestors were enslaved.

The Gullah/Geechee initially bought their lands during the Civil War. By communally owning land passed down generation to generation — also known as “heirs’ property” — Gullah/Geechee people became the first group of African descent in North America to own land en masse.

Over the years, though, threats to Gullah/Geechee land ownership have brought drastic changes through both an abundance of continuous land development and legal loopholes.

“Folks come in with bulldozers,” said Queen Quet to Vice News in a 2016 interview. “And the first thing we see is that they want to dig up what we’ve already had for all these generations. And then they want to build something that’s apathetical to our culture.”

In South Carolina, construction contributed roughly $12.6 billion of the state’s GDP in 2019. More specifically, private nonresidential spending in South Carolina totaled $5.5 billion.

Hilton Head Island was one of the first elite vacation spots, and according to media reports its development reportedly has forced out about 300 Gullah/Geechee families. Land development, including a mixture of golf courses and resorts, has caused such a dramatic displacement of Gullah/Geechee communities, in fact, that one news account stated that burial grounds of Gullah/Geechee ancestors now make up the backyards of million-dollar condominiums.

Initially, heirs’ property arrangements helped to keep extended family properties from development, but over the years, developers have found legal openings, thanks to arcane property law.

“The history of Hilton Head and current Gullah communities reminds me of the concept of ‘highest and best use’ in real estate,” says Jane Harrison, North Carolina Sea Grant’s coastal economics specialist. “Property is appraised with a price that represents what the highest bidder will pay, regardless of the current occupants. People are displaced who do not have the financial capital or power to remain in a place. This process leads to a loss of culture and scattering of traditional communities.”

Overbuilding in the Gullah/Geechee community also has blocked important fishing access points to waterways, and some fishermen end up having to go out on foot, instead of on their boats, to catch blue crab or shrimp.

Quet says access points are essential in order for Gullah/Geechee people to engage coastal areas and to protect them for future generations. Gullah/Geechee culture doesn’t make use of docks, instead making use of landings, but she adds that docks are proliferating along the coast.

“Furthermore, the shading from docks creates a situation where species that may depend on direct sunlight are not receiving it,” she explains. “And as a result, aquatic life who depend on those species will migrate away.”

Natural hazards exacerbate the situation.

“If a tropical storm or a hurricane tears a part the dock, the leftover debris enters the water,” she says. “The people who wanted the private dock end up not wanting to take responsibility of cleaning it out of the water. As humans, we all have a responsibility to protect these waterways.”

Additionally, the Gullah/Geechee Nation has been fighting a 10-year legal action for access to fish along the coast from North Carolina to Florida, ensuring that each state has Gullah/Geechee subsistence rights and laws in place.

However, in South Carolina, conflicts continue to arise among commercial fishers, the state’s Department of Natural Resources, and Gullah/Geechee fishing families, and in Georgia and Florida, the Environmental Defense Fund’s listening sessions in Brunswick and Fernandina documented and discussed broader concerns of African American fishermen, highlighting great overhead costs, diminishing waterfront access, overfishing, and the price of fuel.

RISING SEAS AND CLIMATE CHANGE

“We teach our children the same traditional ways to go out in the water, and the same traditional ways to live from the land, only when things are in season,” says Queen Quet.

Yet, 2019 brought record-breaking temperatures that marked North Carolina’s warmest year on record, and the research- based North Carolina Climate Report projects a continued increase for the state in temperatures, precipitation, storms, floods, droughts, wildfires, and sea level rise.

Meanwhile, climatologists predict that for our neighbors to the south in Charleston, flooding from tidal flows and rain will become more frequent over the next 30 years. According to UGA Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant, scientists expect coastal Georgia to experience at least six inches of sea level rise within the next 50 years as a result of the changing climate. Florida Sea Grant says sea levels will haverisen by 2040 10 to 12 inches above 2000’s levels.

Climate change also brings concerns about water quality; warmer waters can contribute to decreased oxygen levels in rivers and estuaries, which, in turn, will affect Gullah/Geechee resources, such as fish, oyster beds, and other seafood. Moreover, pollutants that have entered waterways from factories also bring health risks for the Gullah/Geechee’s subsistence fishing families.

In addition, as more intense hurricanes and stronger storm surges become more frequent, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) frequently has denied disaster assistance to Gullah/Geechee landowners. A 2017 U.S. Department of Agriculture study found that FEMA turned down claims for approximately 20,000 heirs’ property owners following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita because the Gullah/Geechee reportedly were not able to show clear titles to their land. After Hurricane Matthew in 2016 left many structures damaged, most of the 18,000 assistance claims that FEMA denied in South Carolina counties also involved heirs’ property.

Storms of all sizes, in fact, bring stressors to the Gullah/Geechee community. Flooding can impact fall crops, and even rains and winds that don’t originate with tropical systems can damage what little infrastructure the Gullah/Geechee rely on.

The decision often comes down to choices about what’s affordable to fix. Is it, for example, the leak in the roof or the leak in the boat? Both are crucial to Gullah/ Geechee survival.

Another step the Gullah/Geechee are taking in preserving their culture is educating their youth on the impacts of climate change. “The Gullah/Geechee Fishing Association always seeks to engage the youth so that they can pass down traditional knowledge, all while incorporating current scientific information concerning climate change,” explains Queen Quet.

“It is important for youth, particularly in the Gullah/Geechee community to know how to thrive and survive on the land in order to sustain the culture. In the future, this will help and empower them when it comes to avoiding economical displacement.”

PRESERVING THE HISTORY OF GULLAH/GEECHEE

The Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor is a Natural Heritage Area designed to preserve, share, and educate. The Corridor offers public meetings four times a year, hosts educational programs, and engages with public and private entities on projects and collaborations.

New partnerships with the Gullah Geechee Heritage Corridor promote and enhance tourism development opportunities associated with Gullah/Geechee culture and history. For instance, UGA Marine Extension has been working with the Corridor as well as Gullah/Geechee community leaders on developing better marketing to create and provide different tourism opportunities in Georgia to share the Gullah/Geechee heritage.

Bryan Fluech, associate marine extension director at Georgia Sea Grant, oversees the project. “Although the project is in its beginning stages,” he says, “as an extension agent, a huge part of this whole process has been building internal trust and connections with the community.”

Recently, the Gullah Geechee Chamber of Commerce in Beaufort, South Carolina, also received NOAA support to establish a Gullah/Geechee Seafood Trail, with designs on expanding it throughout the entire Corridor. The project will include extension and program directors from South Carolina Sea Grant Consortium, as well as other partner groups.

Although the Gullah/Geechee Nation faces many threats, continuing initiatives and partnerships can help sustain and preserve its culture and history. In addition, the Gullah/Geechee’s deep connections to the coast have made this community extremely durable.

“We know in the other world, there’s this word called ‘adaptation,’” says Queen Quet. “That word doesn’t exist in the Gullah Language. There’s this word called ‘resiliency.’ Doesn’t exist in the Gullah Language. But we are resilient people who had to adapt to whatever the situation is that’s coming against us.”

Read More:

- Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission

- Gullah Geechee Chamber of Commerce

- Gullah/Geechee Nation

- Quality Counts: A Consumer’s Guide to Selecting North Carolina Seafood

Lauren D. Pharr, a Ph.D. student in Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology at NC State University, also is a science communicator with North Carolina Sea Grant, a Southeast Climate Adaptation Science Center Global Change Fellow, and winner of NC State’s Forestry and Environmental Resources Fellowship for Excellence in Graduate Education.