First Wave

The Pea Island Surfmen Prove Themselves on a Heroic Night

When Richard Etheridge peered out of the tower of the Pea Island Lifesaving Station that he commanded, he could hardly see for the blinding hurricane.

That Sunday night in October 1896 was going to be cold and long. Strong northeast winds whipped around the station on the northern shore of Hatteras Island.

Etheridge, a Dare County native and a Civil War veteran, was the first Black person to be appointed Keeper of a U.S. Lifesaving Service station, and he was the first of a line of Black commanders at the Pea Island Station that lasted more than six decades.

This particular Sunday night, he and his all-Black crew were not going to win any medals, but their heroics would be etched in history.

Caught in the storm was the E.S. Newman, a 393-ton schooner, captained by S.A. Gardiner, en route from Providence, Rhode Island, to Norfolk, Virginia. Gardiner was traveling with eight other people, including his wife and 3-year-old child.

The three-masted schooner ran into the hurricane, which ripped its sails away and blew the vessel 100 miles off course, into seas that were the responsibility of Etheridge and his team.

Surfman Theodore Meekins scanned the turbulent waters from the Pea Island watch tower, where he was on duty from dusk to 9 p.m. The darkness, the blowing sand, and the raging storm made it hard to see, but Meekins caught a flicker of light to the south of the lifesaving post.

The surfman set off a flare. If there was a sinking vessel on the Atlantic Ocean, Meekins wanted to signal the crew that they had been spotted.

“You have to go out, but you do not have to come back.“

The U.S. Lifesaving Service was established in 1848 to provide rescue services to all of America’s coasts. The service merged with the U.S. Cutter service in 1915 to form the U.S. Coast Guard.

The lifesavers’ unofficial motto was You have to go out, but you do not have to come back.

Richard Etheridge, who grew up on the water in Dare County, came to the Lifesaving Service with some command experience already. He had served in the Civil War as a Buffalo Soldier — the first black cavalry regiment in the U.S. military.

After the 1864 Chaffin’s Farm fight near Petersburg, Virginia, Etheridge was promoted to sergeant. The skirmish led to the capture of Richmond, the Confederacy’s capital.

When white Union Army soldiers cheated Etheridge and other African American soldiers of their rations and mistreated their families, Etheridge didn’t let the offenses pass. He wrote to General Oliver O. Howard, the commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau in Washington, DC.: “Our families have no protection, the white soldiers break into our houses, act as they please, steal our chickens, rob our gardens, and if anyone defends themselves against them, they are taken to the guard house.”

Where Others Failed

After the war, Etheridge returned to Nags Head Township, married, and resumed his life as a fisherman and a surfman.

In 1879, Pea Island’s all-white crew, as many Lifesaving Stations had in that era, came under scrutiny for not responding to a British vessel in distress, which contributed to the deaths of 17 crew and passengers aboard. Lieutenant Charles F. Shoemaker, the officer who investigated the tragedy, recommended to the superintendent that Etheridge be given the position of Keeper, after the previous crew was dismissed.

Etheridge had a reputation as one of the best surfmen on the coast. He had worked at the Bodie Island and Oregon Inlet lifesaving stations as a surfman — though not in the top leadership position of Keeper.

In 1880, following Shoemaker’s recommendation, Etheridge became the first Black Keeper of a U.S. Lifesaving Service station, bringing together the all-Black Pea Island lifesavers, who individually were some of the best surfmen on the Atlantic Coast.

At the time, there were 18 stations in North Carolina and 179 in the United States. For the nearly 70 years that followed, Pea Island would be manned by all-Black crews. Etheridge and his men inspired a generation of Black men to join the Coast Guard.

The Well-Prepared, Sharp-Eyed Leader

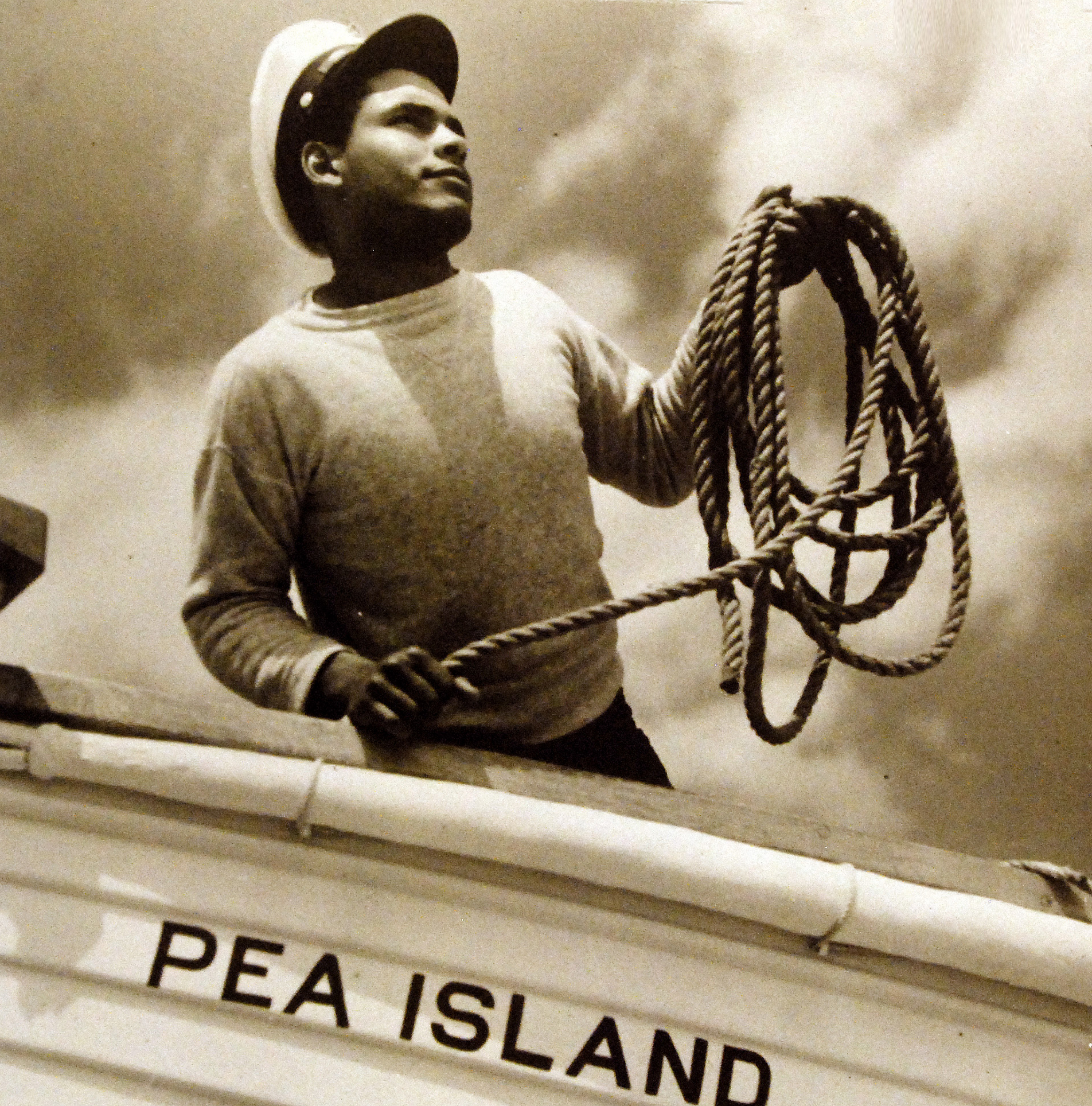

Etheridge’s station consisted of seven surfmen, including himself. Each surfman had a number, a rank. If something happened to the Keeper, the No. 1 surfman was next in line.

At “checkerboarded” stations, those that were integrated, Black surfmen generally were numbers five and six, and performed menial duties, including cooking.

Etheridge understood the burden of being the first Black to hold such a respected position and made sure that no one could question the ability of his crew. He was a sharp-eyed leader who kept a clean station, drilled his men constantly, and kept his equipment in good working condition. Inspectors consistently mentioned his station was one of the finest on the coast.

Etheridge was well-prepared for his role. He had grown up listening to the crash of the ocean, when Dare County was an isolated stretch of land and fishing was its chief industry. So as a boy he learned to fish and respect the power of the water.

As a man, Etheridge was as much a disciplinarian with himself as he was with his surfmen. He was in good shape when he was appointed, reportedly “of strong and robust physique, intelligent, and able to read and write sufficiently well to keep the journal of the station.”

The Pea Island surfmen patrolled the beach from sundown to sunup. One of Etheridge’s surfmen would carry a lantern as he walked north to Oregon Inlet and another surfman would walk south to the New Inlet station. The men would exchange badges with men from the other stations, then return to their outpost.

Etheridge logged the numbered badges, which served as proof that his men walked their patrol area. His journal entries, made four times a day, also included how many boats or vessels passed in a given day and the weather conditions.

As the men walked the 3 1/2 miles out and back, they would be looking for flares in the darkness and listening for the sound of ripping sails. They were also searching for debris that might indicate a ship in trouble.

“The voice of gladden hearts”

On the stormy night of October 11, 1896, the weather was so bad that Keeper Etheridge had to suspend foot patrols.

In the station log, he recorded that the weather at sunrise was “fresh N.E. gale, Stormy” and at noon “fresh, N. Hurricane, Stormy.”

Meekins was on watch in the station’s tower, and when he saw what he thought was a distress signal, Etheridge’s log recounts, he “immediately answered” with a flare. Summoned by Meekins, Etheridge “burned a red rocket, which was answered again with a red torch light. Then it became an evident fact that some vessel was stranded on the beach.”

“The keeper,” Etheridge records, “at once mustered the crew and with the team [of] a pair of good mules started to the scene of disaster with the hand cart and driving cart.”

One of the carts contained a small cannon that would shoot a line across to the wreck. If the vessel was further out in the ocean, the lifesavers would row a boat to it and rescue people as best they could.

But this night, Etheridge wrote, “It seemed impossible under such unfavorable circumstances to render any assistance.” They found the schooner “well upon the beach, with head sails all blown away, cabin stove in, and its effects greatly demolished, yawl boat [lifeboat] lost.” Raging waters thwarted every attempt to get a line on the Newman from shore.

So, Etheridge decided to tie heavy lines to his strongest surfmen and “let them go down through the surf as near the side of the vessel as possible.” Meanwhile, the other surfmen held on tightly to the lines attached to the men.

When the surfmen got close to the wrecked vessel, the Newman crew threw out a ladder, and “each survivor with a line around their body with great difficulty was carried back on the beach.”

The surfmen repeated the ritual until all nine people on the ship were off.

Etheridge wrote in the Pea Island station that night, “The voice of gladden hearts greeted the arrival of the station crew.”

It had taken his men until 1 a.m. to rescue all nine people on the ship.

Etheridge remained keeper at Pea Island Station until his death in 1900. He and his family are buried on the grounds of the North Carolina Aquarium on Roanoke Island, land the family once owned.

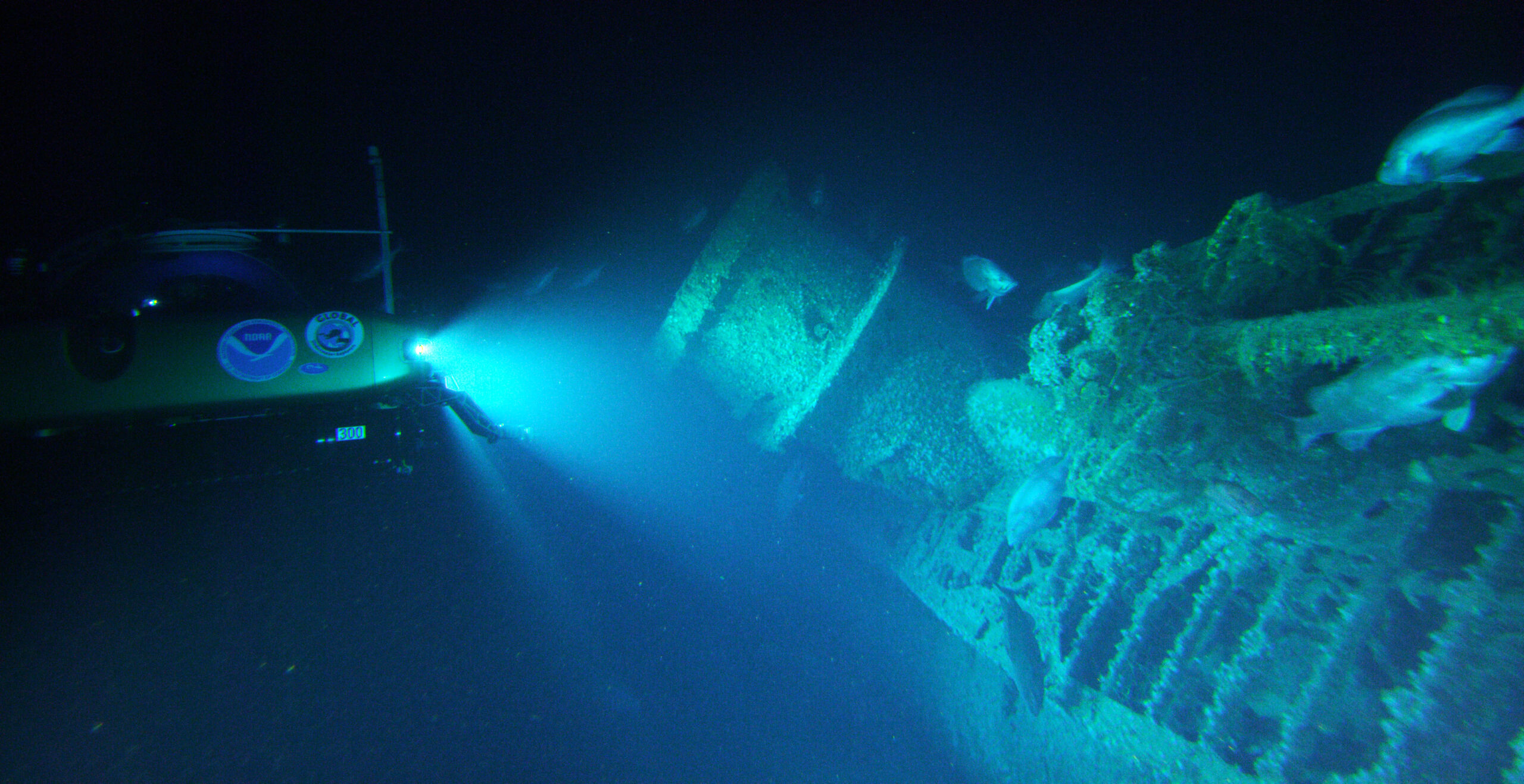

In homage to the all-Black lifesaving crews, the Coast Guard named a 110-foot patrol boat after them. The Pea Island, christened in 1992, was based in Mayport, Florida, where it served as a border patrol vehicle.

Last Fall, The Pea Island Preservation Society, Inc. marked the 125th Anniversary of the E.S. Newman shipwreck and rescue with a Governor’s proclamation and a reunion of descendants. Read more here.

Read more about the U.S. Lifesaving Service.

An earlier version of this story appeared here, courtesy of the African American Experience of Northeast North Carolina, a six-county collaboration that inspires exploration and appreciation of dozens of sites in one of America’s most history-rich corridors. This self-guided discovery begins at NCBlackHeritageTour.com and connects dozens of points of interest and African American influence across a region that includes the Outer Banks, the legendary Dismal Swamp, and some of the state’s earliest riverfront communities in Elizabeth City, Hertford, and Edenton.

Bridgette A. Lacy, a feature and food writer, is the author of Sunday Dinner, a “Savor the South” cookbook from UNC-Press and a finalist for the Pat Conroy Cookbook Prize from the Southern Independent Booksellers Alliance.

- Categories: