Some experienced offshore bottom fishers can read a depth finder display like a good book and identify individual fish species from shapes that most others would refer to as “something big down there.” Unfortunately, fishers never really know what is down there until they see it on video or catch it themselves.

But are times changing?

Research Need

The waters off the coast of North Carolina are home to many shipwrecks that have accumulated over the past several hundred years. These structures hold cultural and historical significance, as well as important habitat for marine life. Shipwrecks are often the destination for offshore fishers and divers, because these structures can serve as fish havens.

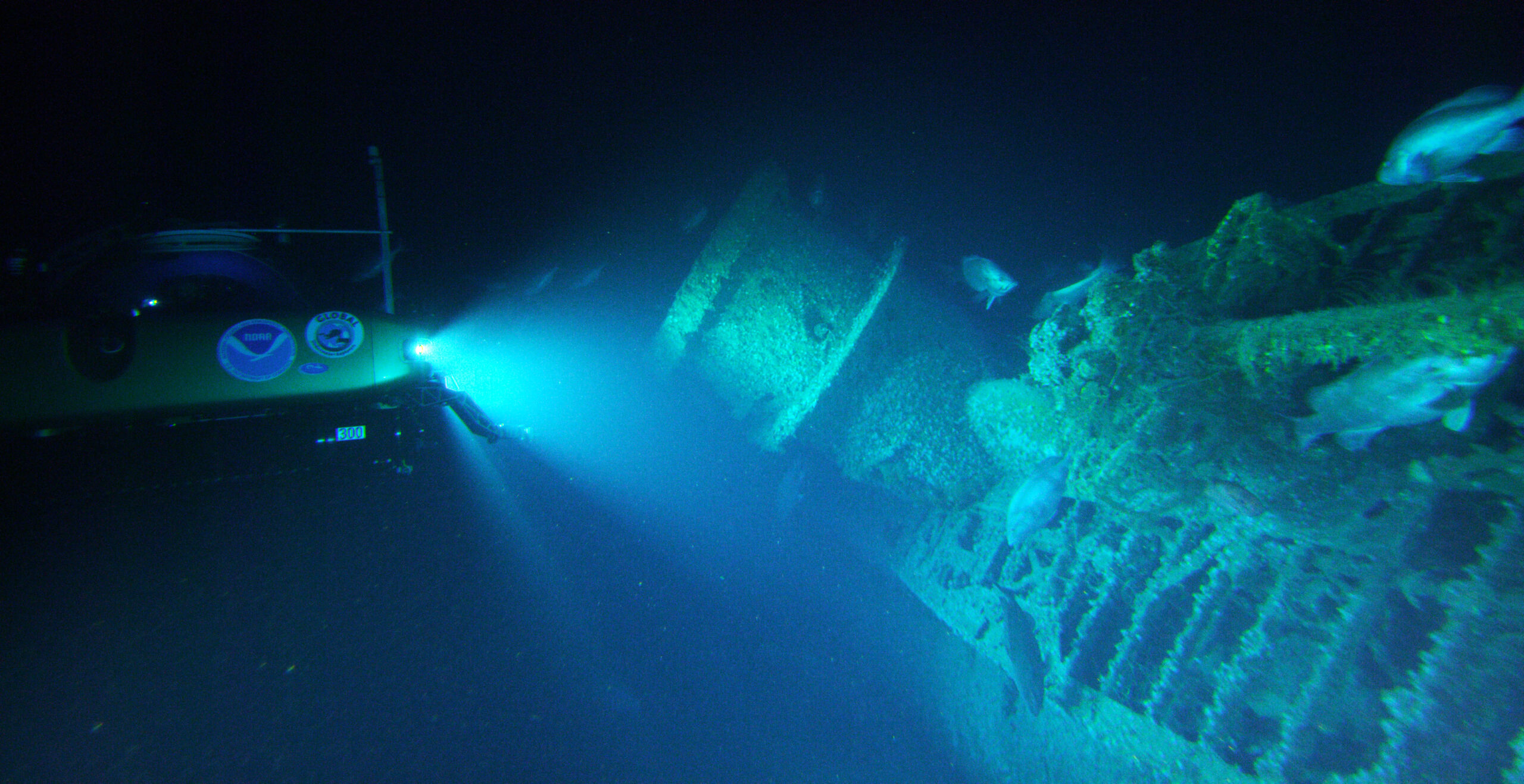

A team of NOAA archaeologists captured on video and with detailed laser-generated imagery the remains of two World War II shipwrecks sunk during the Battle of the Atlantic in 1942. The ships, a German U-boat, U-576 (above), and a Nicaraguan freighter, SS Bluefields, are located relatively close together about 30 miles offshore in 660 feet of water — deeper than the range of most fishers and divers.

When ecologists learned about the availability of the video and imagery, they were interested in using the data to see which kinds of fish frequent these remote, deep-water shipwrecks and where exactly on the wrecks these fish seem to congregate.

Inquiring fishers want to know as well.

What did they study?

A research team utilized two manned submersibles equipped with advanced video and laser scanning equipment to create high-definition video and three-dimensional imagery of the two deep water shipwrecks.

The submersibles made several passes alongside each shipwreck to collect video and create 3-D profile images. From the ecological data collected, the scientists were able to count and identify the fish and their locations relative to each shipwreck.

What did they find?

The shipwrecks hosted several fish species that live close to the ocean floor, including snowy grouper and yellow-edge grouper, among others. Other notable species included wreckfish, Conger eel, and Darwin’s slimehead.

On both shipwrecks, fish concentrated around high-relief shipwreck features. For example, on the U-boat, this included the conning tower, the deck gun, and the bow. A similar pattern of fish behavior has been reported around rocky hard-bottom reefs.

While the research team did not have access to water current data, fish location data suggests that fish are congregating on what appeared to be the upstream side of

each shipwreck. Previous work on shallower shipwrecks on the U.S. continental shelf indicates that this pattern may be common.

Anything else?

The authors note that the study site is the only naval battlefield of World War II on the U.S. East Coast where both the target (the SS Bluefields) and the aggressor (U-576) sank in the same vicinity.

So what?

The success of the joint archaeological-ecological mission has opened the door to additional collaborative ventures, which unmanned underwater vehicles potentially could carry out.

by Summary by Scott Baker, adapted in part from an original article by Heidi Swanson