Dolphinfish, also known as “dorado” or “mahi mahi” (Coryphaena hippurus), is a relatively easy sportfish to catch. The short-lived species grows fast and is popular among anglers and seafood consumers alike. In fact, in 2021, anglers landed 1.9 million pounds of dolphinfish in North Carolina, the most on the East Coast with the exception of Florida, where anglers landed 3.9 million pounds.

Despite the fish’s popularity, its management is challenging due to insufficient data to support a traditional stock assessment. This is especially problematic considering the increasing popularity of dolphinfish among anglers in the South Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico, and the Caribbean since the 1990s, as well as recent research that suggests that the relative abundance of dolphinfish in the Atlantic Ocean has been declining.

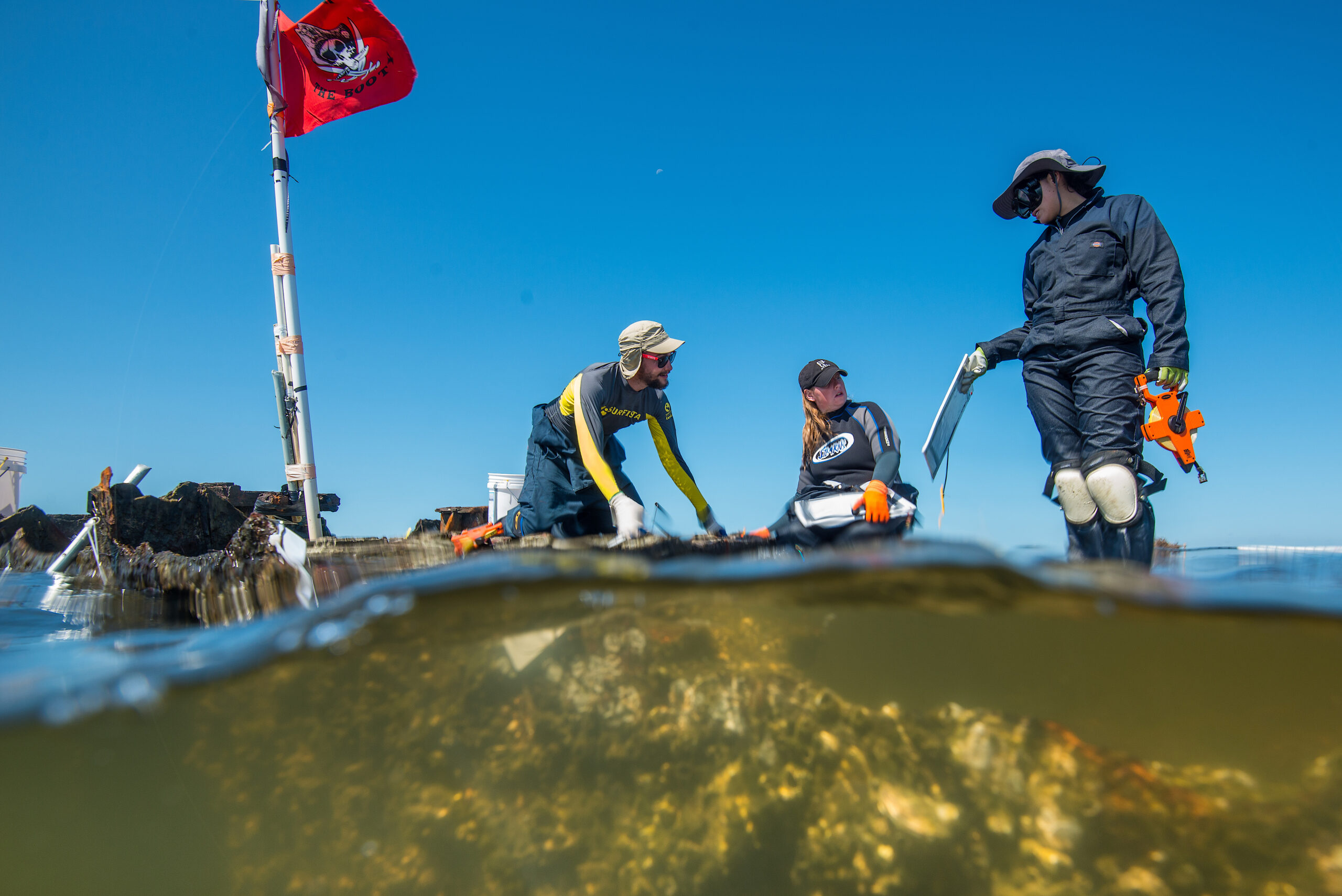

Scientists and fishers have been collaborating to learn more about dolphinfish to better understand the drivers of the population and health of the species. Since 2002, the Dolphinfish Research Program has utilized a flotilla of anglers to capture, tag, and recapture dolphinfish using both traditional and satellite tags. It is the world’s largest fish tagging program.

What did they study?

From 2002 to 2017, the Dolphinfish Research Program distributed over 37,000 tags to 1,313 captains and more than 3,285 fishing mates from around the world. Collectively, these participants took part in tagging and releasing 23,232 dolphinfish, with the majority of fish releases (87%) occurring along the East Coast.

Wessley Merten, of Beyond Our Shores Foundation, and his colleagues analyzed the data to identify participation rates, trends, recapture rates, and movement patterns. The analysis identified gaps in the data and also provided important information — including findings specific to North Carolina and the East Coast.

What did they find?

During the study period, 571 dolphinfish were recaptured. Most fish were tagged off Florida (68%), followed on the East Coast by Georgia/South Carolina (14%), North Carolina (3%), and the remaining coastal states from Virginia north to Maine (1%). Anglers in the Bahamas/Caribbean contributed 13% of tagged fish.

On average, dolphinfish moved northward along the East Coast, from Florida to the Mid-Atlantic Bight, in 44 days. The fastest straight-line movement from Florida to North Carolina was 7 days.

Most tagged fish were 18 to 22 inches in fork length. Most recaptures (71%) occurred within 40 days of tagging.

What else did they find?

Tag recapture data suggests that the Antilles Current (a surface current that meets the Florida Current before joining the Gulf Stream Current) could be a major supply route for South Atlantic dolphinfish fisheries. Enhanced tagging efforts might assist with documenting specific migration routes that dolphinfish take in the South Atlantic.

So What?

The contributions of anglers, particularly those that recaptured dolphinfish, allowed scientists to document expanded movement patterns.

Programs like this one are especially important because financial resources for fisheries management in the Southeast are limited. By combining the interests of anglers and researchers, everyone benefits.

You can sign up for a tagging kit, view a map of the tagging and location data that anglers provided, see who tagged the most fish, and learn more about the project at dolphintagging.com.

by Scott Baker, marine fisheries specialist, North Carolina Sea Grant.