The New Pioneers

An Interview with Jane Harrison, North Carolina Sea Grant's coastal economics specialist

Communities along the coastal Carolinas are taking steps to ensure residents have functioning septic systems and other types of onsite wastewater treatment — as groundwater rises and storms intensify.

Jane Harrison is North Carolina Sea Grant’s coastal economics specialist. In collaboration with university and community partners, she heads a team looking at climate change and onsite wastewater treatment systems. The project will help coastal communities to implement climate adaptation plans. She recently sat down with Coastwatch‘s Julie Leibach to discuss the threats that climate change poses and how some wastewater managers are addressing current and future challenges.

What do we know about how onsite wastewater treatment systems are working along the coast?

It’s difficult to assess. Unless you have an obvious bad smell, visual evidence of sewage, or water rising up in your yard, you don’t necessarily know that your system isn’t working. System owners are likely to assume everything’s okay. But it’s not necessarily okay.

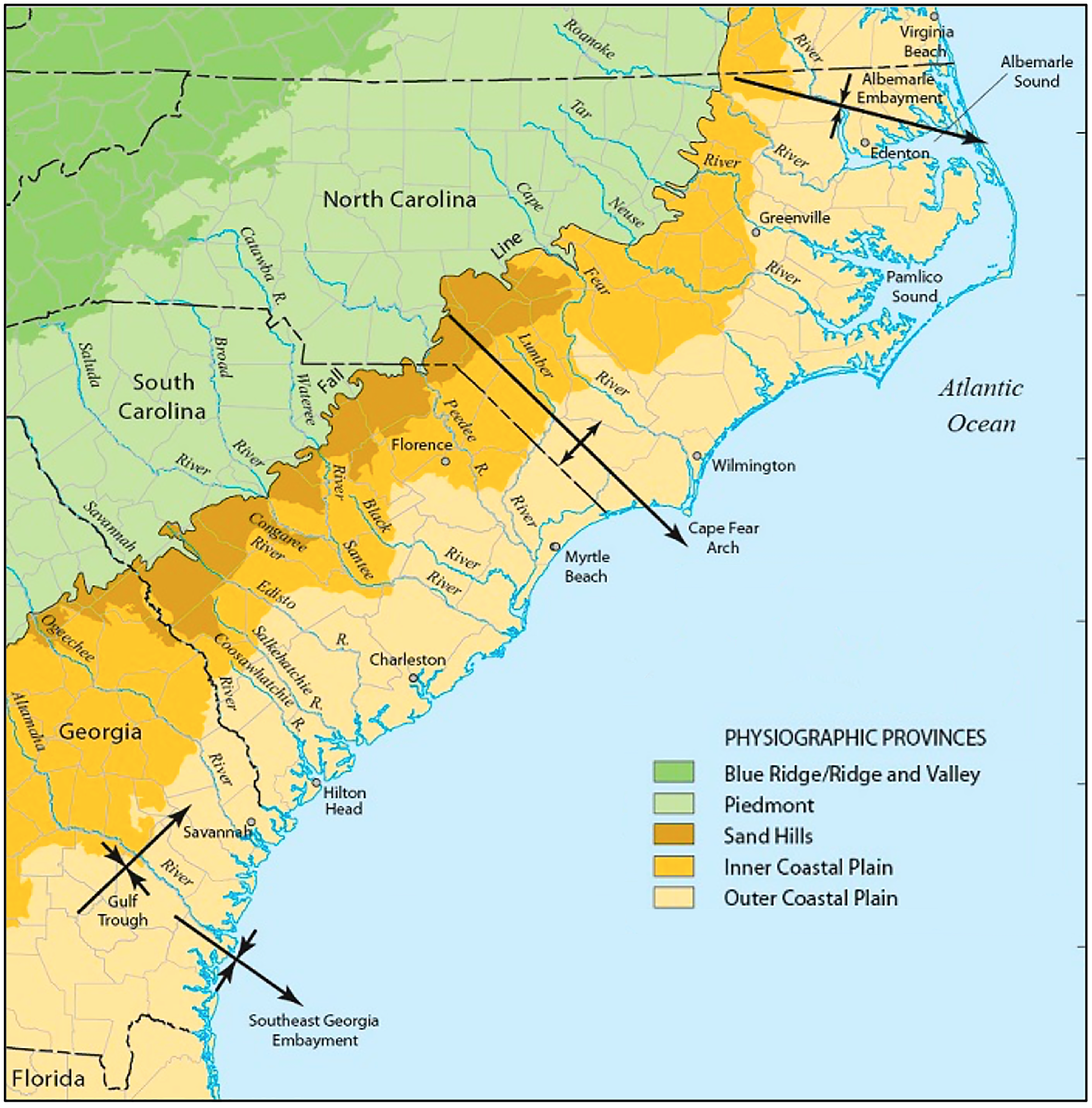

A research team I work with monitors water quality near septic systems along the coast. Charlie Humphrey and Mike O’Driscoll at East Carolina University evaluate inland coastal systems and systems on the barrier islands for treatment efficiency — and now our project allows them to monitor more sites in the town of Nags Head and, in South Carolina, the city of Folly Beach.

We can’t monitor every septic system in Nags Head and Folly Beach, so we’ve chosen different kinds of septic systems and other types of onsite wastewater treatment — like packaged plants, which are cluster systems built to serve multiple households or a small housing development. We’re also evaluating treatment efficiency at centralized wastewater treatment facilities.

Our intent is to gain a better understanding of how on-site and centralized methods impact water quality: in particular, how different types of wastewater treatment systems reduce concentrations of potentially harmful nutrients, including nitrogen, phosphorus, and fecal coliform.

What makes Nags Head and Folly Beach good partners for the project?

The Town of Nags Head has a long history of working on climate change adaptation. They’ve been a partner with North Carolina Sea Grant for years and were involved in a process called “Vulnerability, Consequences, and Adaptation Planning” that we facilitated.

Holly White was a planner with Nags Head and our main collaborator there. She had a passionate interest in climate change adaptation for the town.

Similarly, the City of Folly Beach worked on a vulnerability assessment with South Carolina Sea Grant some years ago, and they wanted to take the next steps and look specifically at septic systems and decentralized wastewater treatment adaptation.

Why do communities in the coastal Carolinas often rely on onsite treatment systems?

For the most part, our coast is less densely populated than the urban areas that can afford centralized wastewater treatment. We need a certain population density to make centralized wastewater treatment plants economically feasible. It’s just not a treatment option in less populated areas.

What are the climate implications of relying on septic systems along our coast to treat wastewater?

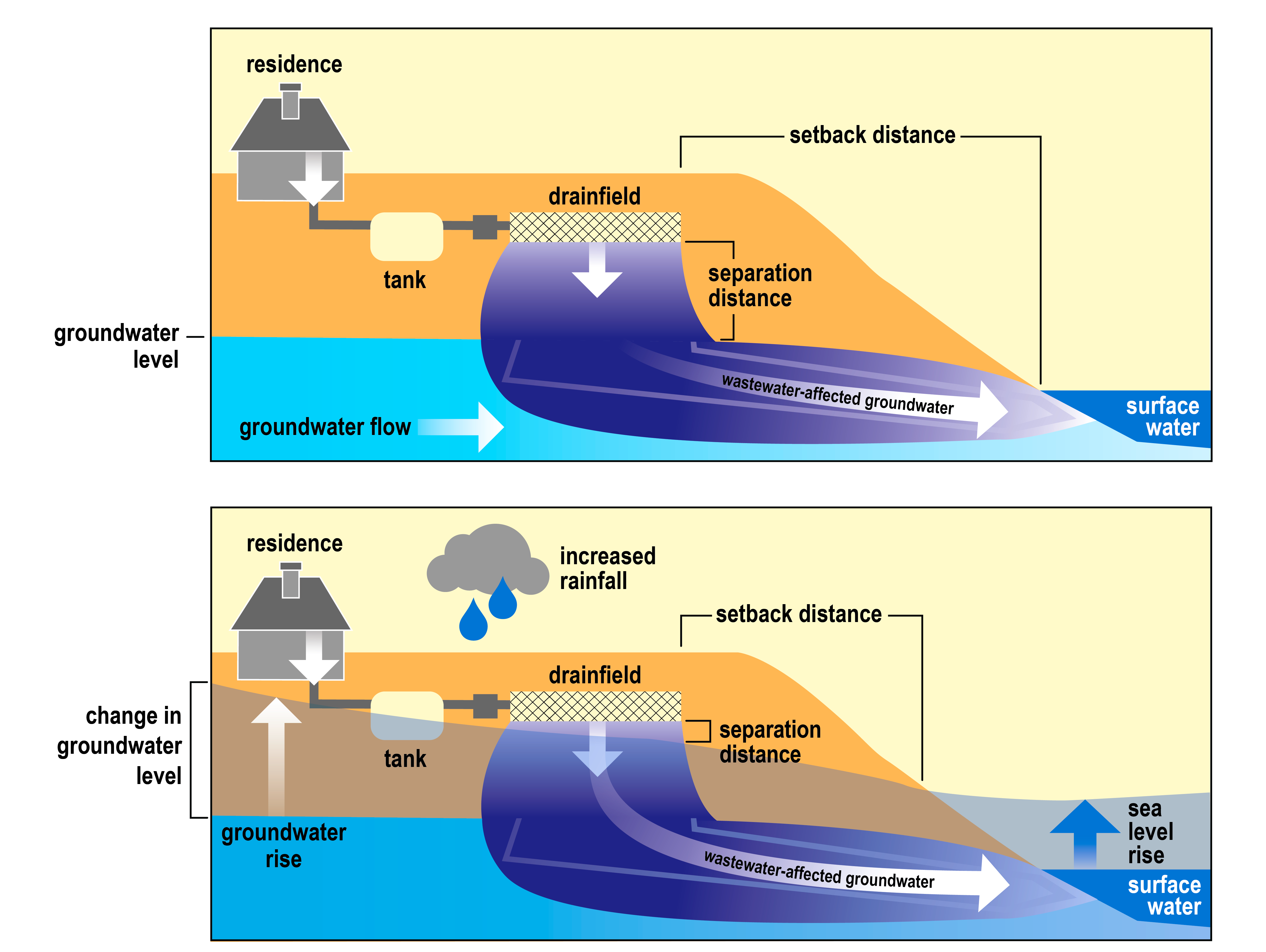

You need dry soil to process contaminants from wastewater. You have groundwater underneath your topsoil layer, and if the groundwater is rising — which is what’s been happening on our coasts because of sea level rise — any untreated wastewater is going to hit that groundwater. Then, it mixes and goes wherever that groundwater goes. Into creeks and streams and lakes and the ocean.

Not surprisingly, contaminants from improperly treated wastewater can cause human illness and damage to ecosystems, and may, ultimately, diminish the quality of life in affected coastal towns and cities.

The vertical separation distance — that’s the distance between the top of your soil layer and the groundwater level — should be between a minimum of 12 to 18 inches for conventional septic systems to function properly. Advanced onsite systems are another option when site conditions aren’t ideal for conventional septic. These more robust systems, though, would have to be required for them to become widespread, because they’re costlier.

A conventional septic system has a tank, drainage line, and soil treatment area. An advanced system often adds pretreatment to the process, some type of additional filtration. Advanced systems cost twice as much as conventional septic — $30,000 to $40,000 vs. $10,000 to 20,000 per property.

You interviewed a lot of people who manage septic systems at the coast. How are they reacting to the changing climate? Are they altering their approaches?

I’m encouraged that septic operators and installers are already adapting to climate change. Now, they wouldn’t necessarily describe their actions in terms of climate change. They’re preparing for current climate. They’ve experienced intense storms, flooding events, hurricanes. They’re not preparing for the future. They’re preparing for what they see year in, year out.

Septic operators and installers are recommending advanced systems to property owners, as well as more conservative installations. For example, they will raise up the soil layer, building in extra soil prior to system installation to create a larger treatment area.

The installers are obviously doing some good things, and that’s important. But if you want to see future-oriented systemic change, we need to see regulatory shifts as well.

We interviewed state and county health department personnel who are responsible for permitting septic systems. The regulatory changes that the health departments need to make — those can account for continued climate change and govern what things look like into the future and on a bigger scale.

And statewide changes don’t happen quickly. Whereas, if a community takes more local ownership of solutions, it can possibly move faster and do what’s needed for its particular area.

And Nags Head is exhibit A.

Yes, I’m excited to see that Nags Head is going forward with a decentralized wastewater management plan. The town is developing a suite of recommendations, in fact, incorporating our research and other work. They are investing in public education on septic use, free septic system inspections, and discounts on pumping out septic tanks, continuing their proactive track record when it comes to climate change.

To see a town get to this kind of granularity on onsite wastewater treatment, on septic systems, is really cool. It’s one of the first examples of a community doing that kind of climate adaptation in a sector that so few communities have figured out how to tackle.

What about the homeowners on the coast who currently are relying on aging onsite systems? How can they rpepare for a storm, for instance?

Basically, you need to prepare to not use your system. The main thing that you can do is let it rest after a storm event, because you need to be aware it’s probably not working correctly, especially if it’s older or not well maintained.

Typically, how well an onsite system will respond to disruptive weather depends on the drainage. Rainfall can saturate the soil and stress the system. The experts we interviewed agreed, though, that onsite systems are generally able to recover on their own if the soil in the drainfield has time to dry out.

Our interviewees also told us that communication to property owners about onsite systems is fractured and inconsistent, which contributes to system failures. Something like the impact-based warnings the National Weather Service uses during severe storm events would be useful for homeowners. For example, with damaging tornadoes, they say “Mobile homes will be destroyed” to motivate people to find shelter. Similarly, severe storm warnings could say “Septic systems may not function properly” and “Wait 48 hours before flushing your toilet.”

How can we best protect our coast’s onsite wastewater treatment systems as the climate continues to change?

We know that older systems often fall through the cracks. An ongoing program that tracks system inspections could ensure systems remain well-maintained and compliant.

We also know that regulatory requirements for onsite systems currently do not take into account resiliency to future climate change. Low-lying areas, such as North Carolina’s Outer Banks and South Carolina’s Low Country, are already experiencing the impacts of sea level rise, and inland areas in the coastal plain are experiencing increases in groundwater table heights. Both areas are particularly vulnerable to extreme precipitation events, which places stress on onsite treatment systems.

Current regulations are inadequate to deal with future climate risks, and this is where state government has a role to play. A next step for our project is taking the results and sharing them with the regulatory community, the State Health Departments, and to hopefully inform their planning and decision-making processes.

We also think that our findings will be useful at the community level for other municipalities as they plan ahead.

North Carolina Sea Grant is leading this project on climate change and onsite wastewater systems, in collaboration with university and community partners and with funding from the NOAA Climate Program Office.

The research team includes:

- Jane Harrison, coastal economics specialist, North Carolina Sea Grant

- Lauren Vorhees, research assistant, North Carolina Sea Grant

- Jared Bowden, senior research scholar, Department of Applied Ecology, North Carolina State University

- Michael O’Driscoll, associate professor of coastal studies, East Carolina University

- Charles Humphrey, Jr., professor of environmental health sciences, East Carolina University

- Eric Edwards, assistant professor of agricultural and resource economics, North Carolina State University

- Katie Hill, J.D., research professional, Carl Vinson Institute of Government, University of Georgia

Community partners have included Holly White, former principal planner for the Town of Nags Head, and Aaron Pope, city administrator for the City of Folly Beach.

lead photo: north of Nags Head in Currituck County, credit: NC State University.

more

- Categories: