CURRENTS: Identifying Innovative Recovery Strategies

Emergency Managers Partner with University Experts, Students

For many residents of central and eastern North Carolina, Hurricane Matthew in October 2016 was at least a double whammy. Some were in the midst of repairs after tropical storms Hermine and Julia just weeks earlier. Others still were grappling with lasting economic impacts from Hurricane Floyd in 1999. Or Fran in 1996. Or any number of flooding events with or without names.

With that challenge in mind, teams of graduate students from NC State University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill embarked on Design Week in January. They visited three communities hit by Matthew’s floods to identify innovative, design-based options for long-term recovery.

At the week’s end, faculty, alumni mentors and fellow students gathered for presentations. So, too, did Mike Sprayberry, director of North Carolina Emergency Management, and several community representatives.

“I am excited about what I have seen today,” said Sprayberry, who leads statewide Matthew recovery efforts that include hundreds of millions of state and federal dollars already allocated, with more expected.

“I want to use the assets in the UNC system,” he added. “It is critical to take advantage of the smart people in our wonderful universities.”

Graduate students in particular are ready to put fresh perspective on the flooding challenges faced by individual communities with limited fulltime staff. “We need to reach out and provide solid planning and a roadmap to the future,” Sprayberry noted. “We don’t want to do the same things as before.”

During the seminar, Sprayberry asks about a proposal to bundle funding from state and federal programs, a new concept that one team calls Community-Scale Assisted Migration, or CSAM.

“To the user, it would all be one program,” replied Adam Walters, an NC State graduate student in landscape architecture. His team had looked at the Belvoir community near Greenville.

The CSAM idea suggests moving residents out of the floodplain but keeping them near their community, he explains. “It would change from seeing the river as destroyer to seeing the river as an amenity, or as identity.”

Gavin Smith, director of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security Coastal Resilience Center of Excellence based at UNC-CH, also was impressed by the 12 teams’ recommendations for Belvoir, Kinston and Windsor.

“This idea has the potential to be transformative,” Smith said of the CSAM concept that proposes using a local community development corporation to build affordable housing within the communities that have buyouts.

Later in January, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development announced North Carolina will receive more than $198 million from the Community Development Block Grants Disaster Recovery program.

NEW PARTNERSHIPS

The CSAM proposal and Design Week overall show how ideas generated by students, in consultation with university faculty, can be considered in statewide recovery efforts, according to Smith, who also is on the UNC-CH faculty in city and regional planning.

Smith is part of that statewide effort. He is advising Sprayberry and Gov. Roy Cooper through the Hurricane Matthew Disaster Recovery and Resilience Initiative.

“I will link applied researchers from across the UNC system to help with Matthew recovery,” he says. The role has some parallels to positions he held in North Carolina after Hurricane Floyd and in Mississippi after Hurricane Katrina.

The Matthew initiative will help agencies, communities and residents to develop disaster-recovery plans that guide redevelopment efforts in communities that were hard hit yet have modest capabilities, Smith adds.

That mission appeals to Susan White, executive director of North Carolina Sea Grant, a statewide interdisciplinary program. “Our outreach staff, funded researchers and graduate students routinely work with community leaders, state agencies, industries and residents on these topics,” she notes.

Through the initiative, Smith and his team will work with Kinston, Princeville, Lumberton, Windsor, Seven Springs and Fair Bluff.

“The team will assess the degree to which policies, codes and plans developed after Hurricane Floyd influenced these communities’ levels of resilience before Matthew struck,” he explains. “This information will help the state assess the degree to which lessons were learned from one event and transferred to another in terms of losses avoided.”

REBUILD OR RETREAT?

When and where to rebuild are complicated questions. In the end, answers may be tied to funding requirements.

The state allocations so far are significant — and more recovery efforts may be considered by the N.C. General Assembly in 2017.

“The most significant provisions of the Disaster Recovery Act of 2016 are those that appropriate $200,928,370 for disaster relief for individuals, businesses and local governments in the counties covered under a state or federal declaration issued for Tropical Storms Hermine and Julia, Hurricane Matthew, and the western wildfires,” Norma Houston wrote in a School of Government at UNC-CH blog.

Some of the funding will be spent by partner agencies working with NCEM.

For example, $20 million goes to the N.C. Housing Trust Fund for housing projects targeting low- and moderate-income individuals and families who are at or below their area’s median income, based on federal guidelines.

Another $20 million goes to Golden L.E.A.F., Inc. and $10 million to the N.C. Department of Commerce Rural Economic Development Division for grants to local governments to construct new infrastructure required for residential development outside the 100-year floodplain. These grants also will fund repair or replacement of existing public infrastructure, such as water, sewer, sidewalks and stormwater drainage systems.

Legislators prohibited the use of state funds for new residences within a 100-year floodplain unless they conform to a local floodplain management ordinance. Also, property owners within that floodplain who receive housing assistance must keep federal flood insurance on the property to be eligible for similar assistance in future floods.

Such requirements set challenges for the state, communities and residents.

“We want to make sure that we rebuild in a methodical and measured way so that the next time we have an event, we avoid losses and increase our economic resiliency,” Sprayberry says.

Plans could include elevating homes and businesses; offering buyouts to save parcels as open space in perpetuity; and expanding economic opportunities, such as an African-American Music Trail.

Kofi Boone, of NC State’s landscape architecture faculty, suggests that students listen, as communities are not likely to trust designers simply arriving with grand plans. For example, after devastating floods from Hurricane Floyd, most residents chose to remain in Princeville — cited as the first town in the country to be established by freed slaves.

Buyouts are solutions that bring challenges, adds Mai Nguyen, on the UNC-CH city and regional planning faculty. Buyouts can be drains on communities’ economies and tax bases.

She also advises students to be sensitive that the floods likely hit clusters of people with low-incomes, the elderly, or other groups with limited resources or complicated needs.

MOVING FORWARD

Andy Fox of NC State, a Design Week faculty lead, sees the teams’ initial proposals as catalysts. “We will continue to look at these same situations through different lenses,” he says.

Through the statewide Matthew initiative, Smith will share not only Design Week results but also other proposals from faculty and students. Officials are eager to hear new ideas.

“We need to use this opportunity to rebuild smart and strong for the future of our communities, businesses and schools,” Gov. Roy Cooper notes.

Billy Barrow, Bertie County Cooperative Extension director, and colleagues see potential solutions in each of the proposals for Windsor and the Cashie River. The Cashie is unique because it begins and ends in one county.

In particular, they say planning requires a better understanding of the hydrology for the river and its watershed. “In Hermine, we were okay,” Barrow recalls. But then Julia brought 5 to 15 inches to the county, and flooding in some sections.

“Then Matthew comes with another 12 inches,” Barrow adds. His office moved between the storms and the library was still packed in tractor trailers months after Matthew.

Allen Castletoe, town administrator for Windsor in Bertie County, is thankful for ongoing assistance from a variety of expert faculty and innovative students. “We are excited about the attention we have received from East Carolina, NC State and UNC-Chapel Hill,” he says.

“We want to be able to know that our plans make sense through an academic review before we go forward to ask for grant money,” he adds.

LEARN MORE:

- NC Emergency Management Hurricane Matthew Portal: ncdps.gov/hurricane-matthew-2016

- Coastal Resilience Center of Excellence: coastalhazardscenter.org

POST-STORM HOUSING NEEDS ARE CRITICAL

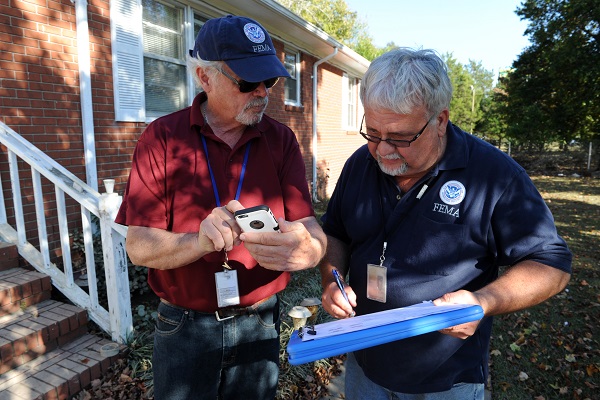

By early February, 81,767 households from across 50 North Carolina counties had registered with the Federal Emergency Management Agency for state and federal assistance related to Hurricane Matthew.

About $92 million in FEMA grants and $87 million in low-interest loans from the Small Business Administration had been allocated to homeowners and business owners to address eligible individual assistance needs. Additionally, the National Flood Insurance Program approved claims of more than $140 million.

For some, Matthew recovery will have a new twist. In January, the state received FEMA funding to provide case managers for some households with complicated recovery prospects. “Families and communities recovering from Hurricane Matthew continue to struggle and they need our support,” Gov. Roy Cooper explains.

More than 1,000 households, many with multiple generations, were still living in hotel rooms in early February. “My primary goal is to get people out of hotels and into housing,” notes Mike Sprayberry, director of N.C. Emergency Management.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development also has awarded the state more than $198 million to address unmet disaster needs. The funds will support housing, economic development, infrastructure and efforts to prevent further damage. Nearly $159 million of that is earmarked for Robeson, Cumberland, Edgecombe and Wayne counties, among the hardest-hit in North Carolina and which HUD identified as predominantly low income.

Also, in December, the N.C. General Assembly approved the Disaster Recovery Act of 2016, a $201 million package that allocated $162 million for Matthew relief.

In addition, donations to the N.C. Disaster Relief Fund will support nonprofits and faith-based organizations assisting survivors.

This article was published in the Winter 2017 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: