CURRENTS: Ride the Currents

Get a taste for the latest happenings with North Carolina Sea Grant staff, researchers and partners from our blog, Coastwatch Currents.

If you visited ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/currents in between issues of Coastwatch, here’s a sample of what you would have found.

There’s a great deal of misinformation — and even a lack of information — surrounding the risks associated with fish consumption. My intention was to find out what residents in the county know about contaminants in the fish they catch and bring to the dinner table.

Why Tyrrell County? Like most of eastern North Carolina, with the exception of the beach communities, Tyrrell is largely rural with high poverty rates. And like most of North Carolina’s coastal plain, Tyrrell abounds with places to catch your own dinner. The county is bordered by the Albemarle Sound on the north and the Alligator River on the east, with a dozen other rivers and streams throughout.

Catching fish in a local stream is a great way to get inexpensive, healthy protein. Except when it isn’t.

All of North Carolina — actually all of the United States — is under a fish consumption advisory for mercury, with special advice for women of child-bearing age and young children because of how mercury affects developing nervous systems. The Albemarle Sound is the only coastal water body in North Carolina with an additional consumption advisory for dioxins, a result of more than a half-century of pulp production upstream.

From Gathering Perceptions of Contaminant Risk in Fish by Liz Brown-Pickren, Sea Grant and Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership fellow, and East Carolina University doctoral candidate.

Gordon [King, who oversees Taylor Shellfish Farms’ mussel farming operations] arranged for us to tour one of the company’s local shellfish beds. He even provided us with the necessary gear — raingear and boots because it was raining, of course, and headlamps because low tide wasat about 9 p.m. Jason Ragan, who directs Taylor’s clam and oyster farming operations, brought us to Totten Inlet.

Although it was rainy and dark, we were able to get an appreciation of the true scope of the production of clams and oysters there on the growing beds at low tide. Jason explained what it takes to plant and grow shellfish. In addition, he gave us some insight on working around large tidal fluctuations and knowing if black bears are near portable toilets.

At night. In the rain.

From East Meets West by Chuck Weirich, Sea Grant marine aquaculture specialist.

Sara Mirabilio may not have grown up on the coast, but that did not prevent her from developing a fascination for the ocean. Her rural New Jersey surroundings did impart, however, a passion for Cooperative Extension.

“I always looked forward to the Sussex County Farm and Horse Show, and as a 4-H member, I earned several blue ribbons,” Mirabilio proudly recalls. “It also meant I understood, even as a young student, how scientific research and new knowledge could be applied to agriculture through farmer education and outreach.”

This understanding, and her passion for marine life, drove Mirabilio to study marine science at Long Island University’s Southampton College. After earning a master’s degree from William & Mary’s School of Marine Science at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, she felt confident in her understanding of marine resources and research.

But, she wanted to figure out how to translate science into policy and action. She gained that experience firsthand in 2002 as a John A. Knauss Marine Policy fellow with the Coastal America Partnership and the NOAA Science Advisory Board.

From Knauss Fellow Sara Mirabilio: Where is She Now? by Diana Hackenburg, Sea Grant science writer and editor.

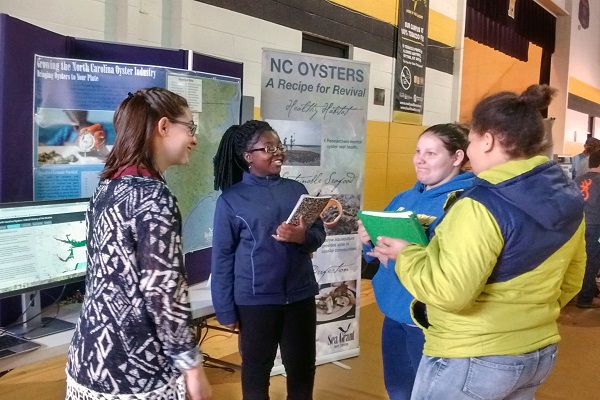

Despite the low hum of an early morning crowd of students, one question resonated throughout the gymnasium: How many of you have a relative in the seafood industry? Dozens of eager hands readily shot up in reply.

Thinking about a future career can be stressful, especially for students in rural areas where many choices involve leaving home for the first time, and potentially, for good. But many students in North Carolina are not even aware of the growing opportunities right in their own backyards.

To highlight emerging careers in the aquaculture and seafood industries, North Carolina Sea Grant collaborated with Mattamuskeet Early College High School to hold an education and career exploration day with local experts. Part of the N.C. Science Festival, the April 13 event offered presentations and hands-on activities to encourage students to look more closely at an industry many of them have been surrounded by their entire lives.

“When Sea Grant sent me information about how they wanted to do a presentation for students, I was very interested,” explains Jennifer Cahoon, an agricultural sciences teacher at the school — and driving force behind the event.

“Fishing and aquaculture are two of our main incomes in the community but many of our students don’t know much about the business end of things. Or they do know about it and feel that it is not relevant in their education, or as a career choice,” Cahoon reveals.

From The World is Your Oyster by Diana Hackenburg.

Longer than 36 football fields, the Benjamin Franklin is the largest containership to ever call on the United States. It can carry up to 18,000 containers, known as 20-foot equivalent units, or teus.

These containers transport everything from the clothes you’re wearing, to the banana you had for breakfast this morning, and the computer that you are using now. A single 20-foot container can hold 48,000 bananas, and if that were the Benjamin Franklin’s sole cargo, it could carry up to 864 million bananas!

The number of people it takes to operate this behemoth across the seas and into our ports to deliver two bananas for every person in the country? Only 26.

As the 2016 Sea Grant Knauss Fellow with the U.S. Committee on the Marine Transportation System, or CMTS, I’ve had the amazing opportunity to meet some of the people who make the nation’s marine transportation system run smoothly and efficiently.

From The Faces Behind our Maritime Industry by Supriti Jaya Ghosh, the 2016 Knauss Fellow from North Carolina.

Many years ago, I married into a Harker’s Island family with a long, rich history of commercial fishing along Core Banks and Back Sound. They fished for whatever was “running,” and that’s what they ate too.

For this reason, my late mother-in-law, Ruth Lewis, knew how to catch, clean and cook every kind of seafood around — and everything she made was exceptional.

Living just up the road from her was rewarding with many, many seafood dinner invitations. She always was cooking away, but never with a recipe.

On many occasions, I observed with great interest as she “baked” flounder in an electric skillet. I thought it was very clever and it was amazingly delicious.

From Baking Fish, Ruth’s Way by Vanda Lewis, Sea Grant food blogger.

This article was published in the Summer 2016 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: