Dogs Days: Estimating Spiny Dogfish Populations

Visitors of all sorts enjoy coastal North Carolina’s warmth and surf all year round.

The human kind show up in the dog days of summer, when the water is warm and the days are long. But as tourists leave and residents hunker down for a quiet winter, chilly coastal waters start to teem with underwater visitors, cruising south from northern summer hangouts.

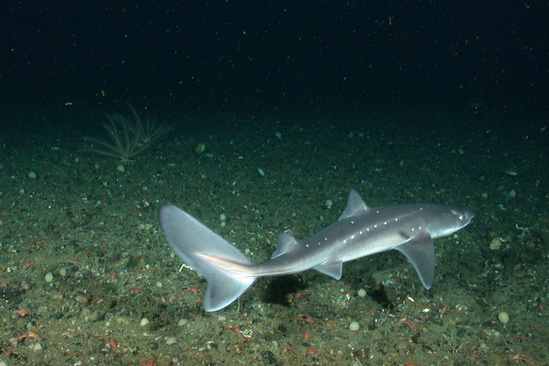

A water temperature that hovers around 47 F in the winter is perfect for spiny dogfish, a small shark that is, on average, two feet long.

For 10 years, Roger Rulifson, an East Carolina University (ECU) researcher, has studied spiny dogfish through funds from five N.C. Fishery Resource Grants (FRG). FRG is funded by the N.C. General Assembly and administered by North Carolina Sea Grant.

In the late 1990s, fishermen Chris Hickman and Eddie Newman approached Rulifson to investigate the declining dogfish population, which crashed soon after. And Rulifson has been hooked ever since.

Last year, Rulifson, along with commercial fisherman Dewey Hemilright and ECU graduate student Kelly Register, attempted to estimate the size and composition of the spiny dogfish population that winters off the North Carolina coast. The group also tagged the fish to determine migration patterns.

The tags have helped Rulifson confirm the dogfishes’ movements in local waters. “They start to come in November and December, depending on the water temperatures.” he explains. The fish migrate north in the warmer days of late March or April.

Hemilright thinks that findings from that FRG study could change how the dogfish fishery is managed both by the state and federal governments. In this simmering dog(fish) fight, federal trawls show a recovering but still low population, while fishers’ nets consistently clog up with the fish. The low federal quotas are in conflict with local fishers’ experiences.

Rulifson’s findings on spiny dogfish correspond with what Hemilright sees occurring on a daily basis in the ocean. In addition, Rulifson has a reputation within the commercial fishing community as a scientist who combines solid research with real-world recommendations.

Hemilright is frustrated at the many limitations within the dogfish fishery but is hopeful there is a solution. There should be a sustainable option that maintains renewable resources and “allows commerce to work and families to make a living,” he says.

“Between catching all you want and catching zero, somewhere there is something in the middle.”

THORNY ISSUES

But where is middle ground? The answer depends on who is asked — fishery managers or fishers.

Every fall and spring, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), an agency within the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, performs a trawl survey to collect data on the abundance and distribution of finfish, crustaceans and invertebrates from Cape Hatteras to the Gulf of Maine. Based on those findings, NMFS develops new regulations for each species.

Historically, spiny dogfish are the most abundant finfish species collected in those surveys. Recently, NMFS has found lower numbers of juvenile dogfish than in the past, Rulifson explains. Either the dogfish “have moved their habitat or they are missing from the population.”

The regulatory agencies maintain that previous overfishing has severely affected the dogfish population, which is slow to mature and reproduce. Therefore, strict regulations are required to allow the population to recover.

Rebuilding the dogfish fishery “is expected to take more than a decade even if fishing mortality remains low, NMFS reports. Also, the long-term spawning stock of spiny dogfish is at risk because there aren’t enough new individuals entering the population, according to NMFS. Seasoned dogfish fishers believe otherwise. Local fishers have to deal with an abundance of dogfish in their nets at a time when they cannot legally land those fish. This problem has affected the bluefish industry, where fishers are forced to venture far offshore to land bluefish.

Otherwise, “their nests choke up with dogfish,” Rulifson says. These long trips burn up precious — and increasingly expensive — fuel and reduce already meager profits.

Recreational fishers also are affected. Charter boat captains “cannot even get the bait down through the dogfish to the striped bass,” Rulifson adds. “All they catch are dogfish.”

North Carolina captains claim that the species population is booming and quotas are too draconian.

“It’s like taking a grain of sand from Jockey’s Ridge,” Hemilright says. “That’s what we’re taking out of there now.”

Further, the fishers argue that NMFS needs to update its trawl surveys to match the shift in dogfish habitats due to changes in water currents and food availability.

MANY MASTERS

The spiny dogfish fishery, divided into federal- and state-managed portions, has several masters.

Stakeholders have to navigate a minefield of regulatory bodies to make changes in the fishery.

The Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council (MAFMC) — North Carolina is a member — and the New England Fishery Management Council jointly regulate the federal fishery, which comprises waters three to 200 miles offshore.

The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) manages the dogfish fishery for 15 Atlantic coast states in estuarine waters out to three miles. Because dogfish are a migratory species, the Atlantic states set their individual regulations within the limits established by the ASMFC.

As of the 2006 NMFS assessment, dogfish no longer are classified as overfished (based on population assessment) nor is overfishing (based on fish mortality rate) occurring.

However, its population — particularly that of the pups — is still below historic levels.

Currently, the federal quota for spiny dogfish is four million pounds, unchanged since 2000.

Separately, the ASMFC came up with its own quota for the spiny dogfish in all Atlantic state waters in October 2006. Based on recent NMFS statistics, the ASMFC raised the spiny dogfish quota from four to six million pounds. But this change was deceptive, fishers claim.

Whether in federal or state waters, “all landings go towards the federal quota,” explains Red Munden, the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries (DMF) representative to the MAFMC and the ASMFC Spiny Dogfish Management Board. Therefore, once fishers harvested four million pounds of dogfish from all waters, they had only two million additional pounds to pull from state waters ranging from Maine to North Carolina.

The fishery is “nothing but a shadow of what it used to be,” Munden says.

Spiny dogfish trade might be reduced by international regulations too. The Convention on International Trade on Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), a Europe-based organization, regulates the global trade of endangered plants and animals. It has 171 member countries, including the United States. Each member has agreed to voluntarily abide by CITES rules.

Recently, CITES placed spiny dogfish on Appendix II, its list of species “that are not necessarily now threatened with extinction but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled.” However, the trade controls will not go into effect for 18 months, to “enable Parties to resolve the related technical and administrative issues, such as the possible designation of an additional Scientific or Management Authority.”

SETTING PRECEDENTS

The dispute between adamant regulators and angry fishers led to the formation of the state’s Spiny Dogfish Compliance Advisory Panel (CAP). The N.C. Marine Fisheries Commission (MFC) felt that North Carolina was “not getting a fair shake” in the dogfish fishery and thus convened the CAP, according to Munden.

“This is the first and only time that the option has been exercised by the MFC,” adds Munden, who provides staff support to the spiny dogfish CAP. Rulifson and Hemilright are also members of the CAP.

After October 2006, the harvest limit per trip in North Carolina waters was 4,000 pounds, while vessels fishing in federal waters had a 600-pound trip limit. As of May 31, DMF lowered the trip limit to 3,000 pounds in state waters, to be in line with the ASMFC’s spiny dogfish Fishery Management Plan (FMP).

Low trip limits have hurt both fishers and fish houses, essentially eliminating the market for dogfish.

“The quota is so low that nobody will cut dogs,” Hemilright adds. Locally caught dogfish have to be sent to the one of two dogfish facilities in Massachusetts — a costly and unprofitable venture.

The CAP gathered data on the dogfish population in the state to determine whether North Carolina should comply with the ASMFC’s dogfish FMP. The state would still be bound by federal regulations because it could not withdraw from the MAFMC.

Ultimately, the CAP agreed to the quotas when the ASMFC raised and redistributed the fishing allocation. Continued membership in the ASMFC “opens the door for North Carolina fishermen to participate in the dogfish fishery,” Munden explains. Otherwise, the state would “no longer have a seat at the table,” he adds.

Withdrawing from the ASMFC — as some suggested — would prevent North Carolina from participating in the formulation of future regulations affecting fisheries along inshore waters. However, the decision to stay in the ASMFC was reached without a quorum. Munden hopes to schedule a meeting of the full CAP later this summer to cast its final vote on the issue.

Yet, there is hope. Reliable results can move even the federal government. Rulifson — through results from an earlier FRG on dogfish and gill net mortality — has been instrumental in changing the mortality rates the federal modelers use.

“I determined that the number that the modelers were using for gill net mortality in

Spiny dogfish school by the bycatch fishery was too high. And so they took the number that I found — actually a lower number than I found — for gill net mortality,” Rulifson explains.

The federal modelers initially assumed a gill net mortality rate of 75 percent. But Rulifson found a rate of 35 percent. The lower rates were incorporated into the 2006 stock assessment.

In his latest FRG study, Rulifson has seen an interesting trend. NMFS reports that the spiny dogfish have a 7:1 male to female ratio. However, he found that the overwintering population in North Carolina has a 13:1 female to male ratio.

“People say that the commercial fishery targets the females. They aren’t going after them on purpose, but they are what’s readily available,” Rulifson says.

In addition, he is finding a large juvenile population. “We’re getting lots and lots of immature, subadult spiny dogfish out there. And they all eat just like adults,” Rulifson explains.

“They ain’t eating water,” Hemilright concurs. The presence of ravenous juvenile dogfish might affect the population of their prey, something the researchers have yet to investigate.

One tagged dogfish was recaptured on the same month and day several years after and within a few kilometers of where it was released.

“That makes me wonder how closely these individual fish are aligned with these great migratory patterns, if they are tied to a calendar of some sort,” Rulifson says. Perhaps the fish habitually return to a particular place at a particular time of year, he muses.

“Rather like ‘snowbirds’ from Quebec or Ontario that drive down I-95 to be there on Sept. 22 to play cards at their little place that they stay for the wintertime.”

For more information on spiny dogfish, visit Rulifson’s Web site: www.spinydogfish.org.

Reports for Rulifson’s earlier FRGs are available at: www.ncseagrant.org under “Research Areas.” The final report for his spiny dogfish tagging FRG will be available later this year.

Dogfish Data

Spiny dogfish by any other name is Squalus acanthias. In Europe, its common name is “spurdog.” In the United Kingdom, it is the fish that pairs with the chips. In Germany and France, the belly flaps of the dogfish are pickled to make schillerlocken — “dogfish jerky” — a treat commonly consumed with beer.

High school and college biology students dissect spiny dogfish, an elasmobranch species. This family includes sharks, rays and skates that have hard, flat scales and skeletons made of cartilage instead of bone.

Male dogfish can live as long as 35 years, while females can live 40 years or more, according to the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries (DMF).

The gestation period is between 18 and 22 months. A female produces between two and 15 live pups, delivering an average of six pups. The pups take 12 to 15 years to mature. The long gestation period, long time to maturity and low birth rate make the spiny dogfish very vulnerable to overfishing because of the time it takes to replenish its population.

The species can be found as far north as New England and Canada and beyond to Greenland. “The only place it does not occur is in the tropics and at the poles and in the polar regions,” says ECU researcher Roger Rulifson.

Historically, North Carolina has been the southernmost point of the dogfish’s range. However, a recent report notes dogfish in South Carolina and Georgia “where they’ve never been seen before,” says commercial fisher Dewey Hemilright.

Spiny dogfish also are found along Europe’s Atlantic coast, although Rulifson does not think the fish migrate across the ocean between continents.

Catching spiny dogfish — a wintertime fishery in North Carolina — is not easy.

Fishing between December and March is dangerous and unpredictable. Nor’easters often disrupt trips, while choppy seas can make it challenging for small 50-foot boats to travel offshore to where the dogfish swim.

Further, some situations depend on the whims of Mother Nature. Last year, due to above-average ocean temperatures, the dogfish stayed north of the Virginia-North Carolina border for most of the winter, according to Munden.

“When the dogfish finally did show up in January, we didn’t get to land them,” Munden says. By then, the federal quota was practically filled. Based on those numbers, North Carolina was only able to land about 100,000 pounds of dogfish compared to Virginia’s haul of 1.5 million pounds, a position that is usually reversed.

Collecting dogfish data is difficult too. “You can be stuck in a hotel for three days, just waiting,” says graduate student Kelly Register.

This article was published in the High Season 2007 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.