John Thomas Osborne has some unfinished business. It’s a project he’s been working on since he was four.

Osborne, a shellfish aquaculture researcher, is opening new doors for North Carolina’s coastal economy. He and business partner Nelson Bullock are trying to grow jewel-quality, saltwater black pearls in state waters.

But these pearls aren’t from oysters. They are from pen shells, an enormous clam-like mollusk found in North Carolina.

From boyhood curiosity to lustrous reality, it’s a winding journey that’s taken Osborne across the world to Queensland, Australia and back to the Wilmington coast. A journey inspired by an innocent bout of mischief over two decades ago.

“Do Clams Produce Pearls?”

You could probably pick Tom Osborne out of any crowd. A frienzied mane of sandy-brown dreadlocks streaming from his head. Inquisitive eyes peering from a scraggly landscape of facial hair. Part Gorton’s fisherman, part Bob Marley.

But in 1984 up in Syracuse, N.Y., Osborne was just another little kid excited to get a card from grandma. He knew it probably had comics or trivia clippings from the papers, which his grandmother in Wilmington, N.C. would send to him every so often.

But this particular clipping planted a seed of inspiration in Osborne that would last for a lifetime.

“[There] was this little tiny thing that said ‘Do clams produce pearls?'” Osborne vividly recalls. “And the answer was ‘No, pearls come from oysters.'”

Osborne nagged his mother with more questions. She briefly explained to him that pearls come from seashells — like the ones they collected when the family lived in Florida and South Carolina — and that shellfish are living things that need water to be alive.

“I had all these shells in my playroom and I was like, alright!” Osborne says. He piled his shells in an old ice cream bucket and got a little Dixie cup to fill it up with water, one cup at a time from the bathroom sink.

Seashells? Check. Water? Check. There was no arguing with this logic: Osborne had everything he needed to make his very own pearls.

Over time, the water would evaporate, which the young Osborne saw as a sign that his shells were “alive” and well, drinking up the water and ready to spit out pearls at any second. Clearly, more water was needed.

Needless to say, four-year-olds don’t have the best balance when it comes to cups full of water. It wasn’t long before an exasperated Mrs. Osborne discovered this nascent aquaculture operation.

“It was driving me nuts!” laughs Annie Osborne. She kept finding trails of water splashed throughout the house, and traced them from the staircase to the playroom.

“I said, ‘Tom! What is this?’ and he said, ‘I’m trying to make you a pearl necklace, Mom,'” she recalls with a smile.

“Oh it just broke my heart!”

Worldly Wanderings

It turns out clams can make pearls, Tom Osborne now knows. But his pearl farm would lay fallow for quite some time. After high school, Osborne went to college in Maryland to study classical literature and philosophy. Marine biology was nary a thought in his mind.

But life is a funny thing. In 2002, a jobless, post-graduate Osborne heard a radio report on how Chesapeake crab harvests were suffering. He thought, Man, that’s really dumb. Why are we still hunter-gatherers? Why don’t we just farm seafood? Let’s get with the revolution!

“So I guess I thought I’d invented aquaculture,” Osborne laughs. After some mild research, it was clear he hadn’t, but Osborne decided his future was in aquaculture.

The adventurous Osborne landed in an aquaculture masters program at James Cook University in Queensland, Australia. The sparkling South Pacific waters nearby have a long history of pearl farming: species of the oyster genus Pinctada are mass-cultured and harvested for pearls.

“I had completely forgotten about [pearls],” Osborne remembers. “And I decided I was going to know everyone who did pearls at the university.”

Paul Southgate, an internationally recognized pearl culture researcher, recalls Osborne as a self-starter: “He always had questions and appeared frequently at my office door, with questions that invariably initiated a conversation about pearl culture.”

Through discussions and field outings, Osborne built a rapport with Southgate’s doctoral students, in particular with Hector Acosta-Salmón, who would become an innovator in conch shell pearls. Osborne even spent two laborious weeks on a commercial pearl oyster barge to gain more experience.

From these scholarly exchanges and outdoor toils, Osborne learned that pearls naturally form when a dead parasite or a scarring cyst — rarely a grain of sand — is trapped inside mollusks such as oysters, clams, conchs and abalone. These animals secrete their calcium carbonate shells using a fleshy organ called a mantle. This mantle may also secrete calcium carbonate around that irritating parasite or cyst.

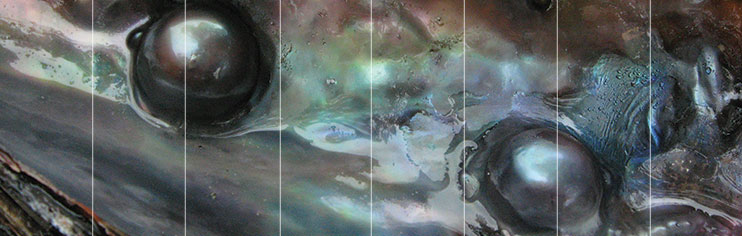

In certain mollusks, however, the mantle also secretes an iridescent layer called the “nacre,” more commonly known as “mother-of-pearl.” In a non-nacreous animal such as our locally eaten oyster, Crassostrea, the encrusted object looks chalky and worthless. But in a nacreous animal like Pinctada, the encrusted object becomes lustrous and dazzling: the pearl as we know it.

Better yet, these prized pearls can be induced. Pearl farmers can insert a polished seashell bead — called a nucleus or plural, nuclei — into an anesthetized animal. Covering it with a scrap of mantle tissue, the mollusk just might be fooled into laying nacreous layers around the nucleus over time. The larger the nucleus, the larger the resulting pear.

Crossing Paths

With all this knowledge in hand, Osborne returned to America in 2006. He found a job with Carteret Community College working for former North Carolina Sea Grant specialist Skip Kemp on oyster aquaculture — the seafood kind. Hearing of Osborne’s interest in pearls, Kemp mentioned that the local pen shells, Atrina, are known to produce nacreous pearls.

But Osborne had even more reasons to be thrilled. Around this time, one of Kemp’s young undergraduates wanted to investigate the possibility of pen shell pearl culture as an independent study project.

That would be Nelson Bullock, a Morehead City native. Between fishing the Crystal Coast with dad and seaside summer camps encouraged by mom, Bullock naturally fell in love with marine biology. But he was truly hooked after a class taught by Theresa Everett at West Carteret High.

“It was one of the few classes I was excited every day to go to,” admits the quiet, bespectacled Bullock. “I was really sad when I left.”

Inspired, Bullock pursued aquaculture training at Carteret Community College. Working as an oyster aquaculture intern, he came to know Osborne.

The two soon realized their mutual interest, and talked over ideas and techniques for Bullock’s project.

With advice from Osborne and others, Bullock explored the pen shell anatomy to determine nuclei placements and experimented with different anesthetics and nuclei types. The goal then was simply to get the pen shells to retain the nuclei while recuperating in fish tanks, and hope for some nacre growth.

But a water pump outage killed the animals, bringing the study to a premature end.

“I found a few nuclei,” Bullock remembers. “But nothing had nacre on it.”

Pearl Fever

Osborne observed Bullock’s progress with great enthusiasm. Despite the lack of initial results, he was impressed with Bullock’s work ethic and research savvy. Osborne had found a friend and a business partner.

By this time, Osborne had also collected some natural pearls produced by pen shells. Found tucked in the gonad of the mollusks, they were unremarkable, tiny dark beads only two millimeters (one-sixteenth inch) wide — yet they carried just a hint of colorful, nacreous shimmer.

“So they’re the proof. They have no nuclei in them. If they’re two millimeters wide, that means one millimeter of growth on either side,” Osborne explains. “Which means that a bead can go from eight millimeters to 10 millimeters. And a 10-millimeter pearl that comes out of North Carolina waters — that’s something special.”

In 2007, Bullock transfered to University of North Carolina Wilmington as part of the aquaculture degree curriculum. Osborne had left Carteret Community College shortly before, but the two stayed in touch. The pearl fever that now swept them both was not about to subside.

The two soon regrouped and picked up where they left off. “We kinda just used our own money and started up the whole project again,” Bullock says.

With that, Osborne and Bullock toasted to their fortunes. The two gazed at the possibilities: their very own company, “Ozlock Shellfish,” bringing pearls to North Carolina!

To secure additional resources for their work, in fall 2007 “Ozlock” applied for a N.C. Fishery Resource Grant (FRG), the fisheries and aquaculture research program funded by the N.C. General Assembly and administered by North Carolina Sea Grant.

The FRG grants committee was intrigued but unconvinced. Gem-quality pearls from pen shells? Ozlock needed to demonstrate more evidence that the plan could work, and that the product would be marketable.

Show and Tell

Osborne and Bullock were undeterred by the committee’s hesitance.

“They had some problems with our methods,” Osborne recalls. “And we decided we’d address them.”

With a little financial help from Osborne’s father, the duo began to work in earnest. In addition to whole nuclei, Osborne and Bullock started experimenting with halved nuclei — half-beads glued to the inside of an animal’s shell, inducing a hemispherical or “mabe” pearl. Osborne called up his old colleague Hector Acosta-Salmón, who mailed them some mabe nuclei to experiment with.

An acquaintance in Topsail Beach offered his dock space to raise the pen shells. The two also took the tiny, natural pen shell pearls they collected to a certified gemologist to gauge the potential market for larger, cultured pearls, and got a cautious but positive response.

With fingers crossed, they reapplied to the FRG program in fall 2008.

Meanwhile, Mother Nature came through with a surprise: some of their pen shells had begun to form “pearl sacs” — the glassy precursor necessary for nacre laying. Osborne and Bullock presented these and other observations at the January 2009 North Carolina Aquaculture Development Conference, and turned a few heads.

The added evidence tipped the balance. In Spring 2009, they received FRG funding.

Eye of the Beholder

Ozlock Shellfish now operates out of Wilmington, where Osborne is working as a part-time educator for the North Carolina Aquarium at Fort Fisher.

Pen shells have been planted in several local habitats to see where they grow best. One impressive set of mabe pearls has already been harvested and will be set in jewelry. Fully round pearls are expected around Christmas 2010.

Tom Osborne should then be one step closure to making good on this youthful promise to mom. “I’m probably third-in-line now,” a proud Annie Osborne laughs, referring to Tom’s supportive and patient girlfriend, Jill Sullivan, and their infant daughter, Eva.

The United States Federal Trade Commission has strict definitions for the pearl trade. Following section 23.18(b) in its Guide for the Jewelry, Precious Metals, and Pewter Industries, Ozlock’s pearls would have to be sold as “cultured pearls” because human intervention induced the nacre growth.

As a trade term, “pearl” alone can only denote a naturally formed pearl, caused by whatever random incidence in the life of the animal. Understandably, the chance of finding a perfectly round pearl in nature is statistically small — hence the higher prices they command over cultured pearls.

But the ultimate value of a pearl is in the eye of the beholder, Osborne says. In a time when some fisheries and coastal trades are struggling, he hopes their black pearls will evoke a sense of pride for North Carolina’s coastal communities and its visitors.

“Fundamentally, it’s shiny stuff. But jewelry is a gift you give to people that’s permanent. It generally commemorates an event, a thought or a place. That’s where that value is. Then if you’ve got people proud to be in North Carolina, people who are proud to be buying something that’s American, they’re going to see that.”

Pearlescent Dreams

Plenty of risks lie ahead. Osborne and Bullock suffered a setback in January when one plot of pen shells became exposed to record freezing temperatures during low tide — resulting in die-offs.

Lesson learned. Don’t set your shells in intertidal beds that completely come out of the water.

Osborne is more worried about the pen shell population itself. “There’s not enough wildstock,” he says. “If people make a run with the wild stock out there, there won’t be anything left to work with.”

For a pen shell industry to succeed, Osborne says a hatchery will be necessary. This way, wild pen shell population levels in North Carolina can remain at sustainable levels, maintaining their genetic diversity and serving as healthy broodstock when needed.

Osborne and Bullock plan to set up such a hatchery this summer in Carteret county, on Bullock’s family property. They’ll test ways to get pen shells to spawn, grow algae soups to feed the pen shell larvae, and build nursery tanks to rear the developing young.

It’s a long way from ice cream buckets and Dixie cups.

Much of the Ozlock hatchery actually will be dedicated to oyster and clam larvae production, selling stock to commercial shellfish growers. But that’s just to pay the bills and keep the lights on. The vision that truly drives Osborne and Bullock, of course, is one that swims in washes of iridescent pinks and turquoise, a mesmerizing kaleidoscope reflected on dark, shining spheres.

This article was published in the Spring 2010 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: