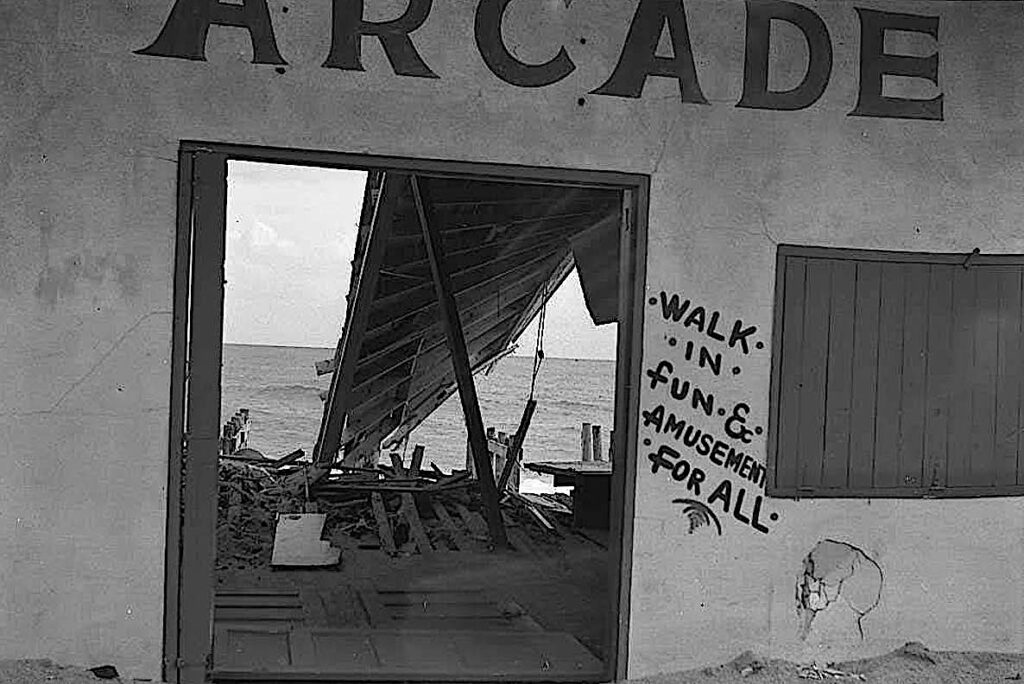

“She had torn the south-facing beaches of Brunswick County all to hell and gone, wrecking the crab-and-fish houses and putting great schooners up into yards in Southport, and thrown fishing boats onto main streets in Morehead City and Beaufort.”

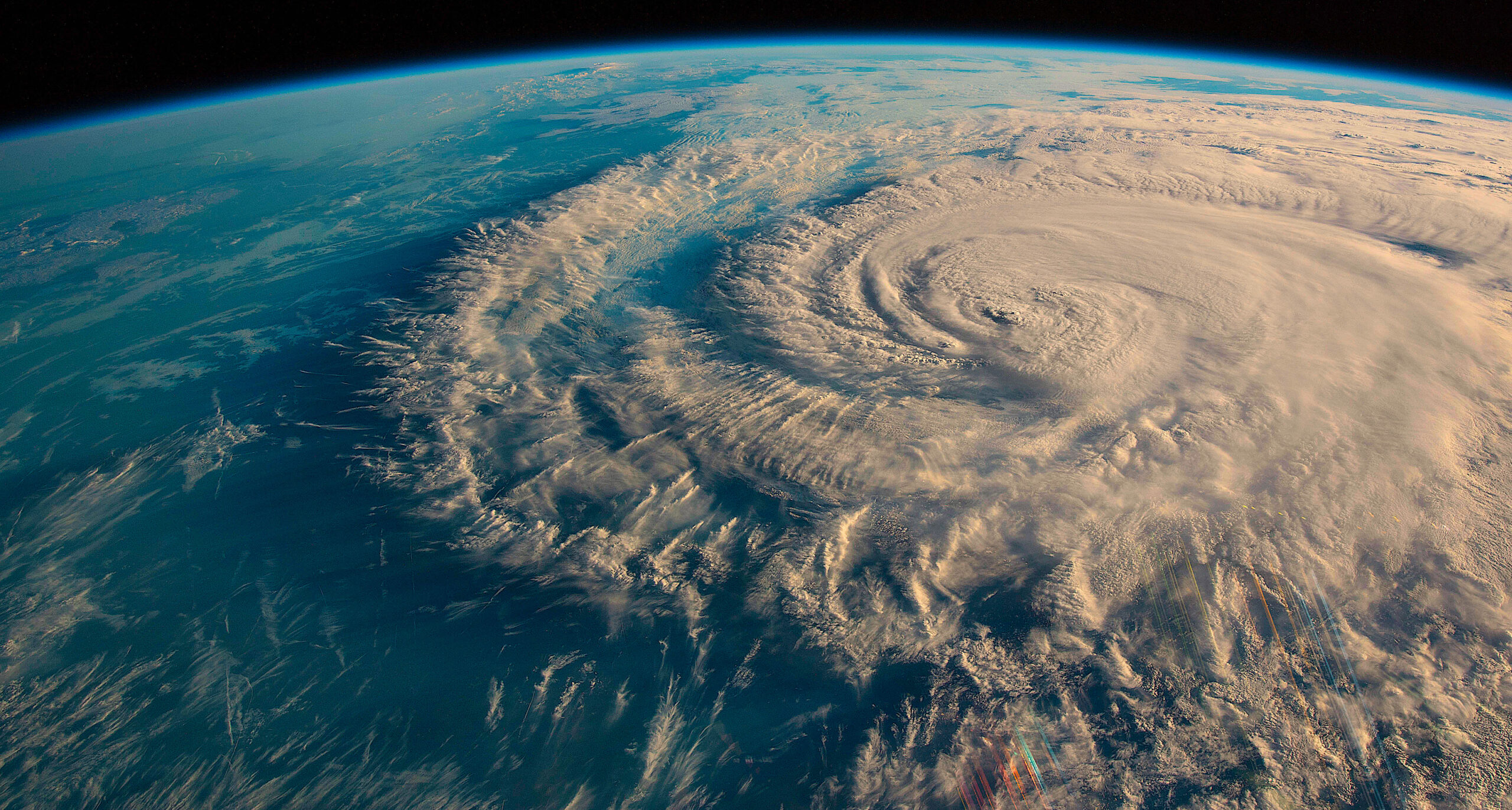

ON THE IDES OF OCTOBER , 1954, A SATURDAY, ON A FULL- MOON HIGH TIDE THAT MORNING , HURRICANE HAZEL SQUALLED INTO NORTH CAROLINA. At 150 miles an hour, she qualified prima facie as both an uprooter and a piledriver, and as a flattener the likes of which no one had seen for over a generation, not since the Great Hurricane of 1933. People called her “the Boulder.”

Throughout that day, my family watched her forces come ahead in Elizabeth City, over 250 miles north of her landfall down in Calabash. We were getting plenty of her rains, and two weeping willows dragged our flooded backyard when their branches were not swaying and swirling crazily like medusan hair in the hold of Hazel’s vicious 90-mile-an-hour sidewinds, far from her eye.

What I recall in the main was sitting for great stretches of time with my father in the window seat of my bedroom, a large, bay-like window, and feeling the power of the noisy sheets of rain as they slammed the glass in a rapid, unending sequence all day long. And watching, as the day faded, a 50-foot maple tree out back lay halfway over before the wind, and our expecting it to snap at any time. As things got dim, lightning then illuminated the backyard, and the lightning images of that tree bent to a 45-degree slant were near-constant ephemera, indelible in my mind for a lifetime.

I was particularly rueful through all this — the next day, October 16th, would be my sixth birthday, and my folks had engaged a pony, for all my young friends and me to have pony rides before ice cream and cake. Naturally, I had looked forward to the occasion and its special feature for many weeks, but now the god Tempest ruled, and the whole affair seemed as doomed as our maple out back. If an all-but-six-year-old could get the blues, then I surely got them, and morosely deep in the grip of them I finally turned in, Hazel’s tailwinds still very hard upon us when I fell asleep.

That Sunday dawned with Elizabeth City and much of North Carolina drenched, yet under a blue sky, and as lovely an autumnal Carolina day as ever there was fell over our river town and my young life in it. The maple tree out back had survived the storm, the night. My gang of friends arrived mid-afternoon, and so did the pony, and we rode it up and down West Williams Circle, one arc of an ancient horseracing track, for the rest of the afternoon.

Hurricane Hazel, by now up in the Canadian Maritimes, could no longer touch us.

Yet, what a forceful touch she had already delivered. At that same moment, people all over our coast and beyond were out taking stock of Hazel’s astonishing toll of wrack and ruin.

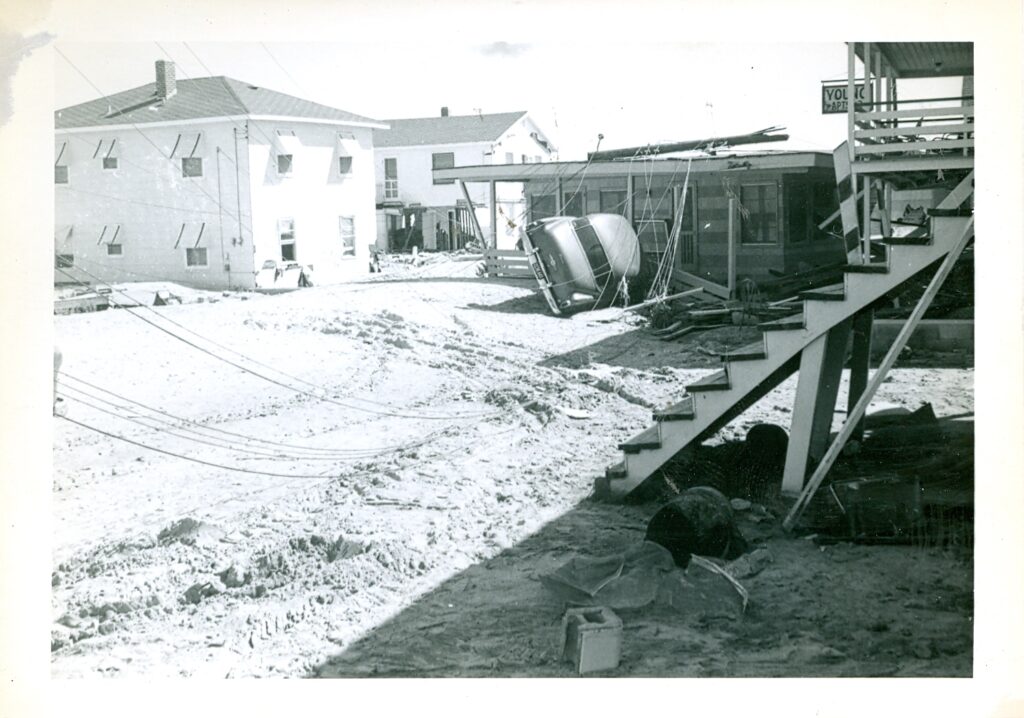

She had torn the south-facing beaches of Brunswick County all to hell and gone, wrecking the crab-and-fish houses and putting great schooners up into yards in Southport, and thrown fishing boats onto main streets in Morehead City and Beaufort. And she had ruined and killed indifferently — only five of 357 buildings left standing on Long Beach, 170 miles’ worth of coastal piers demolished, and 19 people dead here in North Carolina alone.

Still the most powerful hurricane ever known to have made landfall in our state, Hazel also killed social notions that hurricanes were the parochial possessions of the coast and coast alone — for she also marched through central North Carolina, flooding every imaginable creek, river, and basin, knocking down trees and whole forests, and she wrought more havoc on the state capitol of Raleigh, on the university town of Chapel Hill. Much later, hurricanes like Hugo (1989), Fran (1996), Floyd (1999), Isabel (2003), Florence (2018), Dorian (2019), and more would remind us all of Hazel’s long-ago teachings.

All of our best teachers leave us with good, strong questions.

How would we Carolinians fare, Hazel asks, were she — or her like — ever to return?

Ed. note: Bland Simpson wrote this piece before Helene’s devastating impact on western North Carolina. The storm’s flooding, wreckage, and toll on North Carolinians will take years of recovery — leaving his final question unanswered today.

MORE

From Bland Simpson

“This Wet and Water Loving Land”

Ghost Ship of Diamond Shoals: The Mystery of the Carroll A. Deering

Two Captains from Carolina: Moses Grandy, John Newland Maffitt, and the Coming of the Civil War

Bland Simpson, North Carolina’s oft-honored voice of our state’s coast, is Kenan Distinguished Professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He is also pianist for the Red Clay Ramblers, the Tony Award-winning string band, and has collaborated on such musicals as Diamond Studs, Fool Moon, Kudzu, and King Mackerel & The Blues Are Running.

- Categories: