Mapping the Impacts of North Carolina’s Poultry Industry

A Novel Solution to a Lack of Public Data

IT WAS THE SUMMER OF 2016. I HAD ONLY LIVED IN NORTH CAROLINA FOR A YEAR AND WAS ON MY NEW DAILY COMMUTE DOWN I-95 FROM FAYETTEVILLE TO LUMBERTON when the smell assaulted me — an acrid, nauseating, rotting odor. I glanced around to see if there was an evident source when I noticed another clue in white bits of fluff brushing past the windshield, leaving a trail from something just out of sight.

Was it ash? Was there a wildfire? As I crested a hill, a truck emerged, and I realized what downy substance dotted the wind — feathers.

From behind, the truck was stacked at least ten cages high and three across, each filled to capacity with chickens unable to fully stand. I’ve since learned that these trailers can haul 3,000 or more chickens. These frequent interstate confrontations are due to the ubiquity of the facilities: NC produces over 1 billion chickens and turkeys per year and is home to over 4,600 poultry farms.

How might these farms, raising anywhere from 20,000 to 1.5 million chickens at a time, affect nearby (and often under-resourced) communities? How do concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) and their waste, an estimated 2.5 billion pounds annually for chickens alone, impact our state’s waterways? How has the rapid expansion of this industry over the last few decades compounded these problems?

These concerns are part of what motivates Colleen Brown, the 2023-24 joint North Carolina Sea Grant and Space Grant Graduate Research Fellow and Ph.D. student in applied coastal and ocean sciences at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. Her work began as an undergraduate, examining sources of nutrient pollution in the lower Cape Fear River basin, and has evolved into her current research, which investigates water quality changes in the lower Cape Fear River basin over the past two decades.

“What kept coming to my attention is water pollution, specifically the impacts of industrial agricultural facilities on the water here in North Carolina,” says Brown. “But the overarching understanding of what we got from looking at the 20 years of data is that water quality in the lower Cape Fear River basin has been getting worse.”

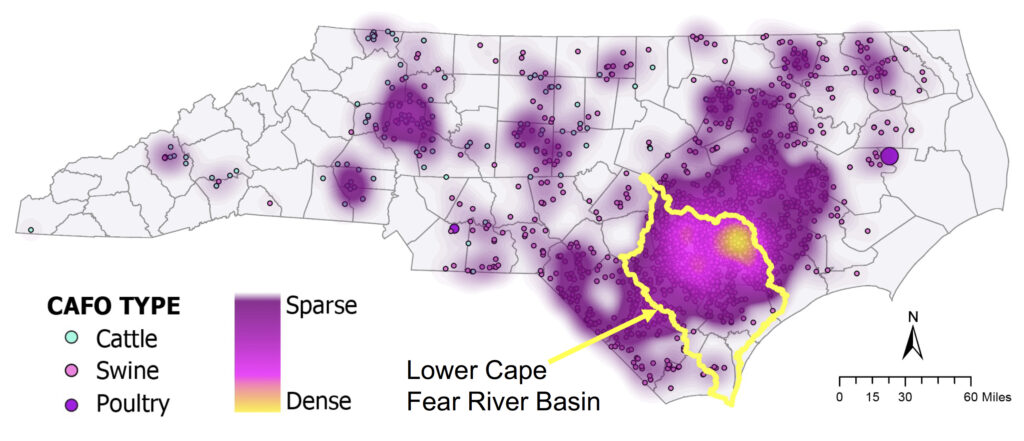

The lower Cape Fear River watershed has the highest density of CAFOs worldwide, containing 10 million hogs, 16 million turkeys, and 300 million chickens, with the most concentrated areas in Duplin and Sampson counties.

Brown used the Lower Cape Fear River Program’s dataset to assess water quality changes for the past two decades at 30 streams throughout the lower Cape Fear River basin. This data indicated increased water pollutants, such as fecal bacteria and nutrients. She hypothesized the state’s growth of poultry CAFOs may be a primary cause.

The possible connection was worth exploring due to the increased concentrations of fecal bacteria and nutrients, primarily nitrate and phosphorous, found in waste and fertilizers. In their efforts to identify the cause of this increased pollution, she and her colleagues considered factors such as population increase, land use change and urbanization, and increased infrastructure, like additional wastewater treatment plants and septic systems.

“I’m focusing on pollutants,” she says. “And the pollution issues, specifically nutrient pollutants in the lower Cape Fear River watershed, have a lot to do with the CAFO industry and the waste.”

Mapping the Problem

Swine CAFOs utilize “waste lagoons” to store wet waste, which farmers later spray onto fields as fertilizer — a controversial practice that could affect air quality and may also make its way into runoff during flooding events. Conversely, poultry CAFOs produce dry litter waste that is less regulated, and farmers often store it covered outside; this storage method is permitted if the litter is not uncovered for over 15 days and more than 100 feet from streams, waterbodies, or wells.

Dry litter does not require a permit, but farms with wet waste need a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit. Per the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), these are required for anyone discharging pollutants “through a ‘point source’ into a ‘water of the United States.’”

Brown started her investigation using NPDES permit records to determine CAFO locations. She created a density heat map from this data and found a correlation between the concentration of these facilities and areas with increased pollution. Because poultry operations are dry litter, this method did not account for their locations.

While the number of swine facilities has remained relatively steady due to regulations, the same cannot be said for poultry. “We know there’s also been an explosion of poultry CAFOs,” says Brown. “What I want to know is, where are these poultry locations?”

Brown needed a record of these locations over time to better understand how facilities could affect state waters. Since there were no NPDES permits or publicly available poultry CAFO location data to trace the growth of poultry facilities, she turned to county-scale survey data of animal production counts, but this still presented an incomplete picture.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) reports the number of chickens produced per county every 1-5 years (survey and census years). According to a 2017 NC Water Resources report, though, information that can be linked to a specific farm is often legally withheld, meaning the reports may underrepresent the total number of chickens produced.

The available data allows researchers to gauge which counties have a high concentration of poultry CAFOs, but the location, size, and quantity of the facilities are unavailable. “When I asked for more poultry data, the UDSA stated they ‘have published what is publishable,’” says Brown.

“But we need to know where they’re located so we can actually quantify the amount of waste they’re adding to the system and then be able to understand the impacts.”

Brown says about 200 million chickens are produced annually in the lower Cape Fear River basin — which, she adds, is about 100 chickens for every person in the lower basin.

“We’re looking at 12 million tons of waste produced a year for the poultry and swine industries each,” she explains. “So, we’re talking 24 to 25 million tons of waste produced in the lower Cape Fear River watershed.”

Brown continued researching other methods to answer her question since permits and surveys could not tell her the location of poultry CAFOs. This eventually led her to machine learning — a subset of artificial intelligence (AI) that uses data and algorithms to “teach” computers. “There’s not a lot of integration of machine learning and water quality science,” she says. “It’s new in the last decade and is an exciting field to explore.”

She developed a successful model that can identify poultry CAFOs from aerial imagery, which will allow her to pinpoint facility locations and overlay them onto watershed maps. Doing so will inform how these facilities affect watersheds, ecosystems, and state communities on a more localized level.

Hidden Costs: The Disproportionate Impacts of CAFOs

Environmental matters are not the only things that motivate this study. “This is also an issue of environmental justice,” says Brown. “We know CAFOs are concentrated in certain areas, and where are they concentrated? They’re disproportionately impacting marginalized communities. The areas with high poverty rates and high percentages of minority groups.”

A 2021 study in Environmental Research found that CAFOs in North Carolina were disproportionately located in communities with low incomes and higher percentages of minorities. Smell and the constant passage of livestock trucks are not the only concerns for nearby residents. Facilities can impact the property values of homes and leave residents unable to sell and relocate.

The Charlotte Observer’s 2022 report, “Big Poultry,” estimated that 230,000 residents in the state live within smelling range (half a mile) of a poultry CAFO, 450,000 are within a proximity that increases the risk for pneumonia (three-quarters of a mile), and 690,000 are within a distance that potentially affects property values (one mile).

A 2023 Environmental Health Perspectives study in NC’s Duplin County similarly found that “people of low income, people of color, people with low educational attainment, and the linguistically isolated in the Duplin Region are disproportionately exposed to higher levels of pollutants [from CAFOs] than the average exposure for residents.”

Research published in Environmental International suggested that CAFOs may be a source of adverse air quality associated with respiratory health for nearby residents. Similarly, a Yale study found that high exposure may contribute to anemia and a higher risk of kidney or cardiovascular mortality.

Brown reports they can cause respiratory issues and impact their neighbors’ quality of life: “CAFOs affect your health and well-being even just living near them. Not even working in one, but just living near it.”

Although poultry CAFOs impact the health of localized communities, North Carolina Field & Family reports that poultry alone creates more than 100,000 jobs for North Carolinians and represents a $34 billion industry.

“We used to have a lot of really small farms in North Carolina, and they’ve been forced into this industrial scale of production over time,” explains Brown. “A lot of these farms are still family-owned, or they’re small farming businesses, but the way they have to operate now is under large corporation contracts.”

Under this arrangement, Brown says, larger companies, or “integrators,” outsource the raising of their livestock to family farms. The corporations provide the animals, feed, and veterinary care but leave the facilities up to the farmer. Per the USDA, this system accounts for 99.5 percent of broiler chickens in the U.S., and local farmers told the Charlotte Observer in 2023 that it leaves them with little control, unexpected costs, and massive amounts of debt.

“The small farmers have to provide the buildings, they have to provide the land, they have to manage the manure, hire the workers, and do everything,” says Brown. “And then you have these big integrators that own the animals. They don’t have to deal with pollution. They’re not the ones having to handle the manure and waste and regulations.”

How do we reconcile economic needs with environmental concerns?

“Industrial jobs are important to North Carolina,” says Brown. “They’re crucial for our economy, and they’re crucial for the wellbeing of our people. We obviously need farms. We need healthy food. And we need food that’s not just healthy for us to ingest, but also food production that’s healthy for our environment.”

CAFOs and Climate Change

“Climate change can intensify pollution from CAFOs and other agricultural practices,” says Sarah Mehdaova, North Carolina Sea Grant’s coastal public health specialist. “Extreme weather events like heavy rainfall and floods can lead to the overflow of manure lagoons and the spread of pollutants into nearby water bodies.”

The subsequent pollution of waterways with excess nutrients, “eutrophication,” can cause toxic algal blooms, decrease oxygen content, lead to fish kills, and result in unsafe concentrations of fecal bacteria in waterways.

“The thing is, we’re all wetlands here in the coastal plain,” says Brown. “There are a lot of ways that the nutrients are cycled through a system naturally, but when we keep adding more, it’s the issue of the excess.”

According to the EPA, agriculture can also degrade well water, which is a concern for the 2.4 million North Carolinians who rely on it.

“Agricultural practices, particularly the use of fertilizers and pesticides, can significantly affect well water quality,” says Mehdaova. “Private wells, which are not subject to the same regulations as public water systems, are particularly vulnerable.”

Brown says this pollution is out of sight.

“You’re not seeing it, and a lot of people think seeing is believing. You can see an algal bloom, but you’re seeing the effect and not necessarily the pollutants themselves. You’re not seeing it until it’s already impacted people when it’s serious.”

Furthermore, the chain reaction that eutrophication sets off can also lead to ocean acidification, which, according to NOAA, can affect wildlife populations and development, lower harvest rates, and eventually increase seafood prices.

“Agricultural pollution has been highlighted by the United Nations as one of the largest contributors to coastal eutrophication,” explains Brown. “It doesn’t just impact our local drinking water sources and ecosystems. It goes directly into the Atlantic Ocean, which impacts our global ocean’s water quality.”

Machine Learning, Environmental Research, and Looking Forward

These issues of environmental justice, pollution, and climate change reinforced Brown’s desire to locate poultry CAFOs in NC and determine their influence on state waterways. However, this required acquiring an entirely new skill: machine learning.

Brown used publicly available aerial imagery (from the National Agricultural Imagery Program) to “teach” her machine learning model to identify swine CAFOs (distinguishable by the presence of a waste lagoon), poultry CAFOs (no waste lagoon), and areas with neither.

Her current model is at over 95% accuracy for classifying aerial images.

“In the next couple of weeks,” she says, “I will start to get the point locations of CAFOs and eventually create a public database where people can access the locations. Open science is a big thing for me because collaboration is key.”

She can then overlay these locations onto watershed delineation maps and compare them to the Lower Cape Fear River Program’s data on water quality. This will allow her to determine to what extent poultry CAFOs have influenced pollution in NC’s lower Cape Fear River basin.

Brown’s work reveals the utility of machine learning and AI in addressing environmental issues. The UN Environment Program has integrated AI for monitoring methane emissions, tracking air quality, and measuring environmental footprints, while NASA and NOAA have also started implementing it in their work.

However, Brown is also mindful of recent concerns about AI’s environmental impacts due to its energy consumption. “It’s not without a cost that weighs on me: How can I study one form of pollution but be ignorant to another?” she asks.

Brown plans on transitioning into a career as a water quality scientist who uses integrative approaches to solve water resource issues. Her dream has been to work with NOAA, and now she’s interested in a career with NASA, which she didn’t believe was possible until this project.

“At the North Carolina Space Symposium, a scientist gave a presentation on using machine learning and satellite imagery to help understand flooding changes,” she recalls. “That’s so similar to the research I’m doing.”

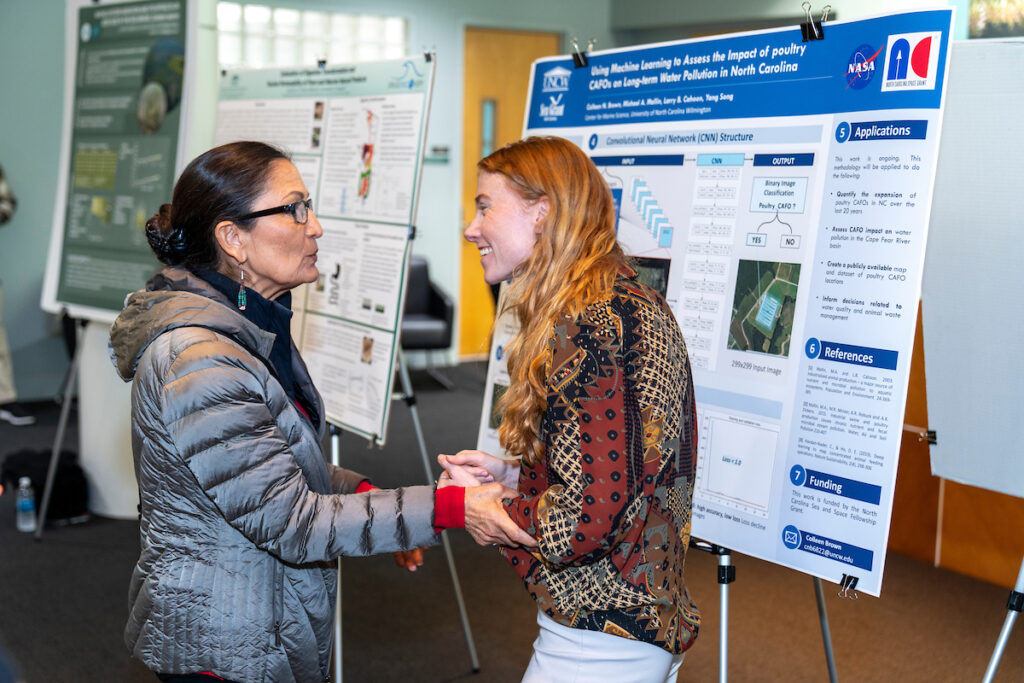

Brown previously presented her research to the United States Secretary of the Interior, Deb Haaland, and the Director of the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Liz Klein, during their visit to the University of North Carolina Wilmington’s Center for Marine Science.

“Secretary Haaland is the embodiment of an Earth steward,” Brown says. “She’s a steward of the environment. She’s a steward of the people. She was so thoughtful and really listened. I mean, what a beautiful thing for her to visit, and then you have solidarity with somebody who also understands these issues and is encouraging of the research behind them.”

Brown hopes her findings will help policymakers and the future health of NC’s waterways and that her model can serve as a framework for researchers elsewhere. “It’s not farmers versus scientists,” says Brown. “We’re all on the same side when it comes to wanting clean water and a healthy community.”

MORE

NC Sea Grant and Space Grant Graduate Research Fellowship

2024 North Carolina Space Symposium

Coastwatch on the disproportional effects of flooding and water quality: “Troubled Waters: Flooding, Contaminants, and Heightened Risks”

Coastwatch on healthy ecosystems

Charlotte Observer report on “Big Poultry“

NOAA’s “What is eutrophication?“

Cape Fear River Watch CAFO information

Marlo Chapman is a science communicator with North Carolina Sea Grant and a contributing editor for Coastwatch. Her writing also has appeared in American Scientist. She recently graduated with an M.A. in English from NC State University.

- Categories: