Satellite tagging on Bald Head Island reveals that loggerhead sea turtles cover long distances up and down the East Coast — and beyond.

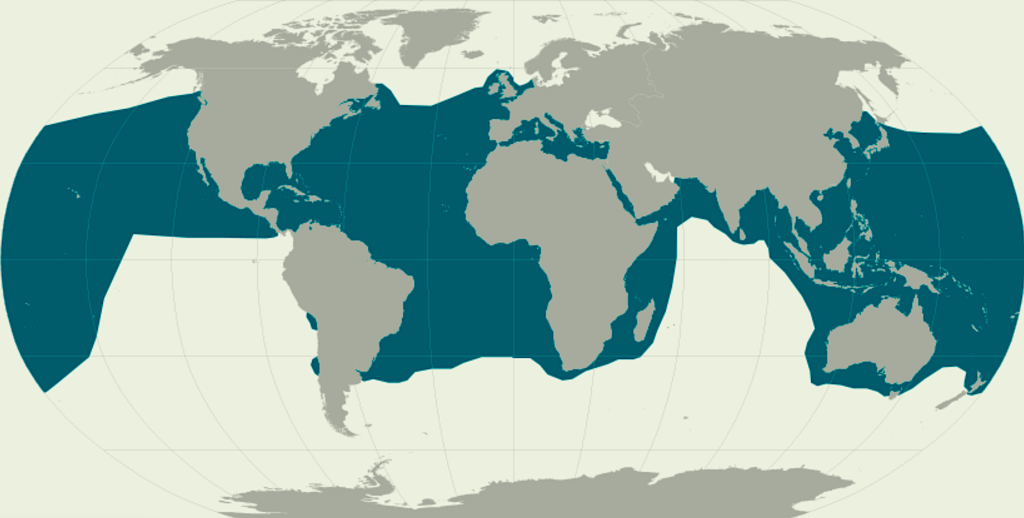

DESPITE THEIR POPULARITY, THERE’S STILL MUCH WE DON’T UNDERSTAND ABOUT THE OCEANIC LIVES OF LOGGERHEAD SEA TURTLES (CARETTA CARETTA). We know about their preferred diets and how many eggs they lay, and we know that nesting females return to the region where they were born to nest (for example, Cape Fear, North Carolina). A human born on the same day as one of these stunning marine reptiles likely won’t live as long. Sea turtles of several species can live 100 years or longer.

What we don’t know very much about is how they spend their time at sea.

On Bald Head Island, a dedicated sea turtle protection program aims to learn more about what their loggerhead sea turtles get up to when nesting season ends. Bald Head Island Conservancy’s sea turtle biologist, Paul Hillbrand, and his team attempt to tag every nesting turtle that visits the island. To make sure they don’t miss any, the sea turtle protection team patrols the beaches by UTVs (utility terrain vehicles) from dawn until dusk, effectively becoming nocturnal from late May to early August.

Hillbrand, sea turtle technician Karlee Szympruch, and four interns wake at 4:00 p.m. to start preparing for the night. They’ll head for the beaches at 9 p.m. and won’t sleep again until 8:00 in the morning. In addition to identifying and tagging turtles, they spend their nights collecting data and biological samples, placing protective cages over nests, relocating nests in precarious locations, keeping hatchlings safe on their way to the ocean, and educating curious beachgoers about their research and the ecology of sea turtles.

“We don’t just play with turtles,” Hillbrand says. “We’re conducting collaborative research, sea turtle protection, and it’s not easy.”

Because Hillbrand’s team attempts to identify every nesting turtle, Bald Head Island is one of two “index” beaches in North Carolina (along with Hammocks Beach State Park, almost 75 miles north). The data collected from index beaches informs predictions about sea turtle population trends.

Most sea turtle programs identify nesting mothers through genetic analysis rather than direct contact, which can be quite time consuming. As a saturation tagging beach, the Conservancy’s team intercepts and attempts to identify every one of Bald Head’s sea turtles in real time —an accurate and time-saving approach that the NC Wildlife Resources Commission sanctions through permits. Flipper tags and passive integrated transponders (PIT tags, inserted into each turtle’s shoulder, like a microchip) allow the team to identify individual turtles and track their nesting habits.

“If we don’t attempt to identify every turtle,” Hillbrand says, “we’re not doing our job.”

The primary focus of satellite tagging for the Conservancy is to better understand how sea turtles utilize their habitat, especially in proposed and leased ocean wind farm properties along the East Coast. The tags have depth sensors to indicate the types of dives the sea turtles engage in, allowing the team to infer when their turtles are resting and feeding based on time-specific records.

“We’re learning how long their nesting intervals truly are,” Hillbrand says. “The satellite tags are exposing summer foraging grounds, overwintering grounds. They’re really showing that not all turtles are alike, and the boxes we try to put them in, they’re busting out of.”

Satellite tagging also gives Hillbrand and his team unique insight into the migration patterns of their nesting sea turtles. The satellite tags send out a signal every time the turtles surface for air, creating a map of the turtles’ travels over time. “Scarlett,” one of the Conservancy’s popular nesting mothers, has been satellite tagged in 2017, 2021, and 2023. Hillbrand says that each time, the data shows she follows the same migration route “like clockwork.” After nesting, she always heads north to feeding grounds off the coast of Ocean City, Maryland, and then she heads south to overwinter in the waters off Charleston, South Carolina. She even changes direction, north or south, on nearly the exact week as in prior years.

“She’s a creature of habit,” Hillbrand says, “but there are other turtles that aren’t.”

Bald Head hatchlings tend to head toward the Sargasso Sea, while nesting moms swim north to the waters off the North Carolina capes and farther north to New England, or down to the waters off Florida at the end of nesting season. However, there are plenty of sea turtles who break the mold.

“‘Alexis’ comes off the coast of Bald Head Island and then just goes to the Bahamas, never to be heard from again,” Hillbrand says. “‘Sandy’ is an east girl. She goes out off the continental shelf and does a huge circle in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.”

Hillbrand hopes the Bald Head Island Conservancy’s sea turtle protection program will continue to become more research-focused, not only in terms of monitoring turtles but also actively publishing accumulated data regularly. It’s exciting to look to the future and ponder what the trails of Bald Head’s sea turtles will reveal about sea turtle behavior and how they use their habitats.

MORE

Bald Head Island Conservancy’s sea turtle protection program

Coastwatch on sea turtles and critters of all kinds

Morgan Greene is the marketing associate at Bald Head Island Conservancy.

- Categories: